Unlike the Orations (the Collect, Secret, and Postcommunion), which are renowned for their precise parsimony, the Roman Canon abounds in what a lesser mind might be tempted to call “useless repetitions.” Why the does the priest say that we are praying and beseeching instead of just praying? Why does he bother to ask that the gifts be accepted before they are blessed? Why does he call the gifts three things (these gifts, these presents, these sacrifices) when only one word would have sufficed? And why does he petition to God to “grant peace to, preserve, unite, and govern” the Church instead of something simple like “watch over” her? How, in other words, can we assent to the Catechism of the Council of Trent that there is nothing “useless or superfluous” in the Latin Mass when the Canon seems rife with verbal superfluities or what Dr. Christine Mohrmann called “monumental verbosity”? [1]

The short answer, I believe, is that ornamentation is not superfluity because ornament is not ornamental. In Latin, ornamentum refers to equipment or furniture as well as decoration. In the theater it refers to the costume of a character; in architecture, to “the enrichment of a building so as to clarify use or purpose;” [2] in rhetoric, to the make-up or style of speech. Cicero’s On the Orator elucidates four traits of a speech’s ornamenta:

that we should speak correctly and in pure Latin;

next, clearly and distinctly;

then, gracefully (ornate);

then suitably to the dignity of the subject, and becomingly, so to speak; [3]

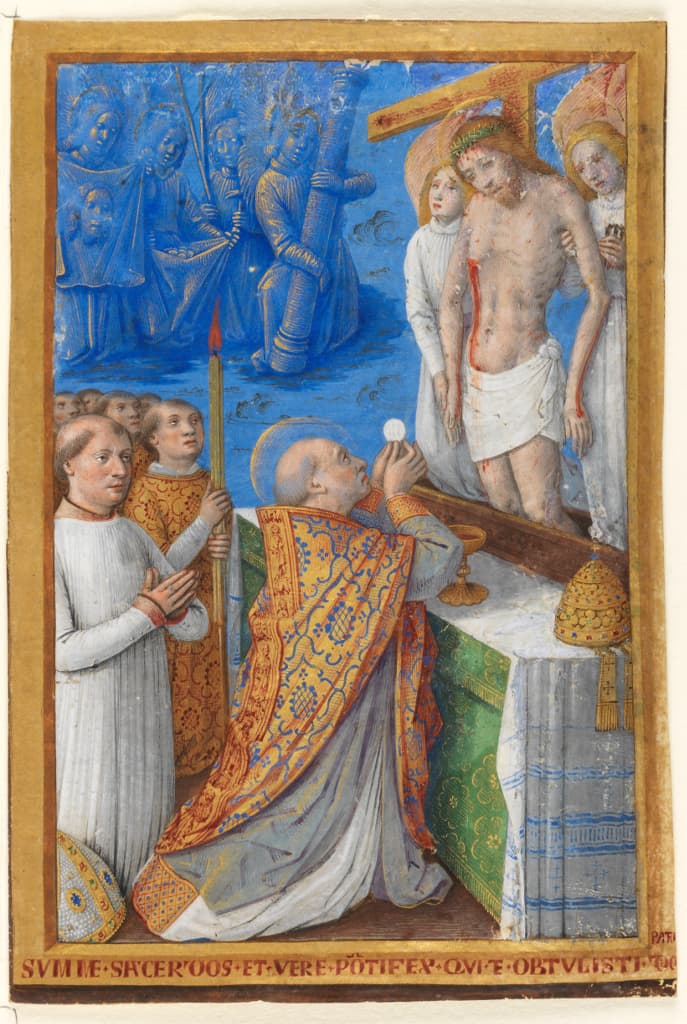

The third and fourth traits are related in that the greater the dignity of the subject, the more suitable it is to have graceful or ornate speech. One need not channel the Bard when telling one’s child to take out the trash, but it is a different story when it comes to asking one’s God to turn bread and wine into the form and matter of His crucified and risen Son. In the case of the Canon, there was a double goal: 1) to reflect the awe and mystery of the Action through words, and 2) to coopt “the kind of language used in the old pagan cultus so that Christianity could replaces paganism and assume its status as the true cultus publicus of Rome and the empire.” [4] And both goals were met, producing “a remarkable combination of Romanitas and Christianitas.” [5]

The “extra” words in the Canon, then, are not redundant or superfluous, but the apt response to a rhetorical necessity, namely, of the duty of matching the dignity of the language to the dignity of the subject. It is in this way that ornament is not ornamental, that is, it is not a dispensable option but a vital sign by which the importance of the thing is signified.

And the words in these ornate sentences of the Canon have been carefully arranged. In the sequence haec dona, haec munera, haec sacrificia (these gifts, the presents, these sacrifices), the order is ascending. Dona can refer to any gift great or small; munera refers to more formal gifts or tributes, the word that the Secret uses the most for the oblations (bread and wine); and sacrificia refers to a total gift to God that transforms the gift itself. Such is the journey of bread and wine, which is: 1) given to the priest before the Mass or during an Offertory Procession, 2) offered to God by him, and 3) then turned into the Lamb that was slain.

Similarly, the petition for the Church, that it receive peace and be preserved, unified, and governed, has an ascending order. Imagine a Church at war with her enemies both external and internal. The first step for a remedy is to stop the war through peace. But since things can decay and dissolve even during peacetime, the next step is to preserve them. Having preserved members is a good thing (like specimens in formaldehyde), but even better is to have them unified into a single, living whole. And yet this unified Body will come to no good unless it is governed and guided by God.

Syntax

As a classicist friend of mine likes to joke, word order in Latin is not important—until it is. In this case, making Te the first word gives it prominence. And that word, of course, points to our most clement God the Father, to whom every Mass is offered, through the Son and with the Holy Spirit. The opening word of the Te igitur therefore underscores the theocentric focus of the Canon and of the Mass. And this focus is reinforced by the priest’s concomitant gesture of looking up to Heaven in imitation of Our Lord who lifted up His eyes before giving thanks to His Father. (see Jn. 11,41)

Diction

Finally, four brief remarks on word choice.

First, igitur is a postpositive conjunction (i.e., it can never be the first word in a sentence) that like, ergo and a couple of other Latin words, means “therefore.” Where it differs is that it can have the added meaning of resuming an interrupted thought, as with the English expression “as I was saying.” Seen in this light, the Canon is but the continuation of the dialogue begun after the Secret and interrupted by the Sanctus. To paraphrase:

“Let us give thanks [Eucharist] to the Lord our God.”

“It is meet and just.”

“Yes, it is meet and just to give thanks…and to join the Angels in singing.”

[Singing] “Holy, Holy, Holy...”

“And so, as I was saying, we beseech You, o most clement Father…”

Second, the adjective illibatus is a striking choice for modifying sacrificium. It is usually translated as “unspotted”—or, as in the 2011 ICEL translation, “unblemished”—which is understandable since in the pre-Christian era illibatus was paired with nouns like virginitas [6], and in the Christian era with words like victimae and fides. [7] Nevertheless, illibatus literally means “undiminished.” Illibatus is the past participle of in-libo; in here means “not” while the verb libo means to take a little from something. But libo also means “to pour out in honor of a deity”: in other words, to make a libation. [8] Could the word choice mean that the sacrifices being mentioned, which currently consist of sacralized but untransubstantiated bread and wine, have not yet been “poured out to God” because they are not yet His Precious Blood? In that case, the most accurate translation of haec sancta sacrificia illibata, albeit the least eloquent, would be “these holy and [at present] un-libationed sacrifices.” My sense is that the author’s intention was, as most translators think, to convey the sense of “unblemished,” but I also suspect that he deliberately chose a word with rich sacrificial connotations.

Third, the Biblical word for bishop is episcopus, but the Canon refers to the local ordinary as antistes, a word that originally designated a high priest of Rome’s old civic religion. [9] Perhaps this repurposing of Latin is a way of coopting the high parlance of the imperial court and putting it in the service of the heavenly court.

From here...

...To here

Fourth, the Canon refers to Christian worshippers as cultores, whereas other parts of the Mass use other terms such as the faithful (fideles) or members of God’s household (familia). Cultor was also a term used for pagan worshippers, but its origins are agricultural. The verb from which it is derived, colo / colere, means to take care of or tend; a cultor, then, is a cultivator, “one who bestows care or labor upon a thing.” [10] Keeping this etymology in mind, we can think of all orthodox believers as cultivators of the Catholic and Apostolic Faith. Only orthodox believers can be cultivators; heretical believers are not cultivators but destroyers who sow the field with cockles or weeds: of them does Our Lord say, “An enemy hath done this” (see Matt 13, 24-30). And orthodox believers, this noun reminds us, do not keep the Faith as if it were a butterfly in amber, but as if it were a garden in need of constant attention, protecting it from pests, nourishing it with love, and pruning its excrescences (such as wrong turns in developments doctrinal or liturgical or invasive innovations). May God bless His gardeners of the Catholic and Apostolic Faith. [11]

Notes

[1] Catechism of the Council of Trent, Ch. 20, §9: “Of these rites and ceremonies let none be deemed useless or superfluous: all on the contrary tend to display the majesty of this august sacrifice, and to excite the faithful, by the celebration of these saving mysteries, to the contemplation of the divine things which lie concealed in the Eucharistic sacrifice.” See Christine Mohrmann, Liturgical Latin: Its Origins and Character (Catholic University of America Press, 1957), 68.

[2] Denis McNamara, Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2009), 25.

[3] De Oratore 32.144

[4] Mark R. Francis, Local Worship, Global Church: Popular Religion and the Liturgy (Liturgical Press, 2014), p. 62.

[5] Christian Mohrmann, 69.

[6] See Seneca, Controversiae 1.2.12.

[7] See St Jerome, Commentarii in IV epistulas Paulinas, ad Titum 1,8-9.

[8] “Libo, -avi, -atum,” I.B.2, Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary.

[9] See Christine Mohrmann, “Notes sur le Latin liturgique,” Études, Tome II, (1961), 104-105.

[10] “Cultor, -oris, m.,” II.B, Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary.

[11] On a side note, the 2011 ICEL translation expresses a noble sentiment but it is not the one found in this passage: “and all those who, holding to the truth, hand on the catholic and apostolic faith.” (p. 635) Instead of cultivating, the translation speaks of tradition, of handing on. Also, “those holding to the truth” is, in my opinion, an inadequate and unnecessary translation of “orthodox.” It would be more accurate to say that the Truth holds us than that we hold to the truth. Orthodoxy does not mean truth-holding but right belief and right praise. The latter meaning anticipates the next sentence in the Canon (the Memento) in its description of the faithful offering the sacrifice of praise.

Finally, all English translations (including my own) treat orthodoxis as the adjective of cultoribus but in fact it is a noun linked to cultoribus by atque. The most literal translation, therefore, is “and all orthodox [believers] and worshippers of the Catholic and Apostolic Faith.”