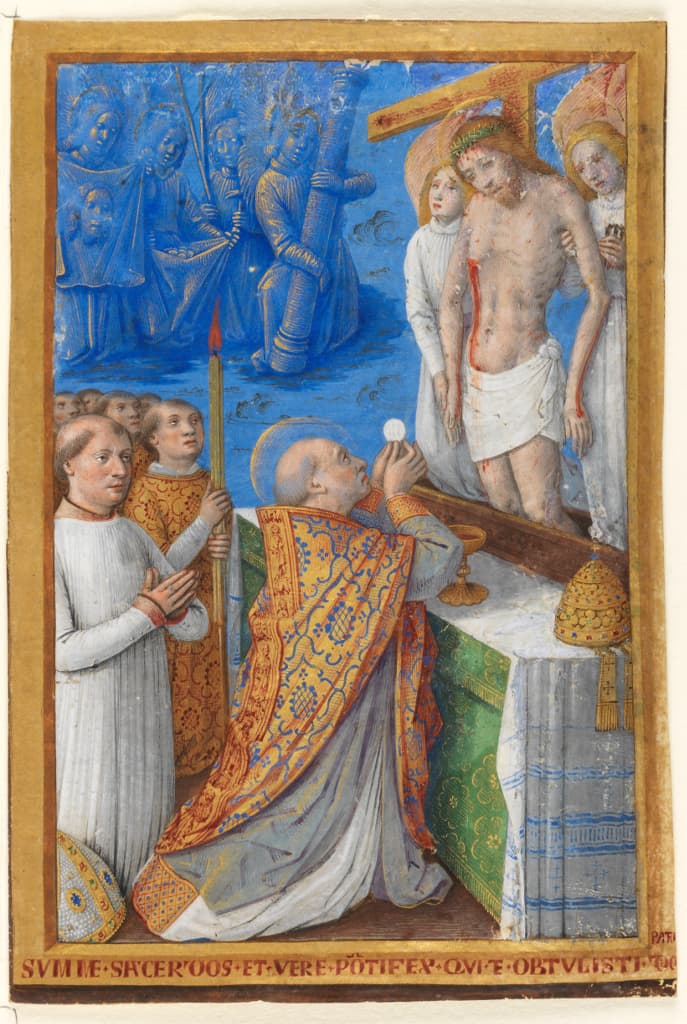

From the 1570 Missale Romanum

Lost in Translation #132

For most of its history, what the 1970 Missal calls “Eucharistic Prayer I” was known as the Roman Canon. Pope Vigilius (537-555) referred to it as the prex canonica [1]; by the end of the century, it was simply the canon/canonis. “Canon” in Greek means norm or rule; the canonical Scriptures, for example, are recognized as the norm for written divine revelation while the apocryphal writings are not. Similarly, the Roman Canon is (or used to be) the norm by which a priest in the Roman Rite confects the Eucharist. There is, however, one difference between the two: whereas the words of the biblical canon do not change, those of the Roman Canon do. There are different versions of the Communicantes and Hanc Igitur for certain times of the year, the names of the sitting Pope and local ordinary change, and the priest’s private intentions for the living and the dead can vary with each Mass, intentions which the rubrics presume he utters aloud in the same voice as the rest of the Eucharistic prayer.

Infra Actionem

Before “Canon” became canonical, so to speak, other titles vied for the honor. [2] These included the sacrificiorum orationes, legitimum, regula, agenda, secretum, and even the “dangerous Lord’s Prayer” (orationem dominicam quae dicitur periculosa). [3] But perhaps the most compelling alternative name for Canon is actio or the Action. The word could be short for actio gratiarum (thanksgiving or “Eucharist”) or agere sacrificium (to make a sacrifice). A curious rubric in the Roman Missal (including the 1970/2002 edition) attests to the synonym. As previously stated, the Communicantes in the Canon has different versions, and to alert the priest of this fact, the Missal states immediately before the prayer(s) the following in red: Infra Actionem or “within the Action.” That is, “Within this Canon be prepared to make this or that insertion.” [4]

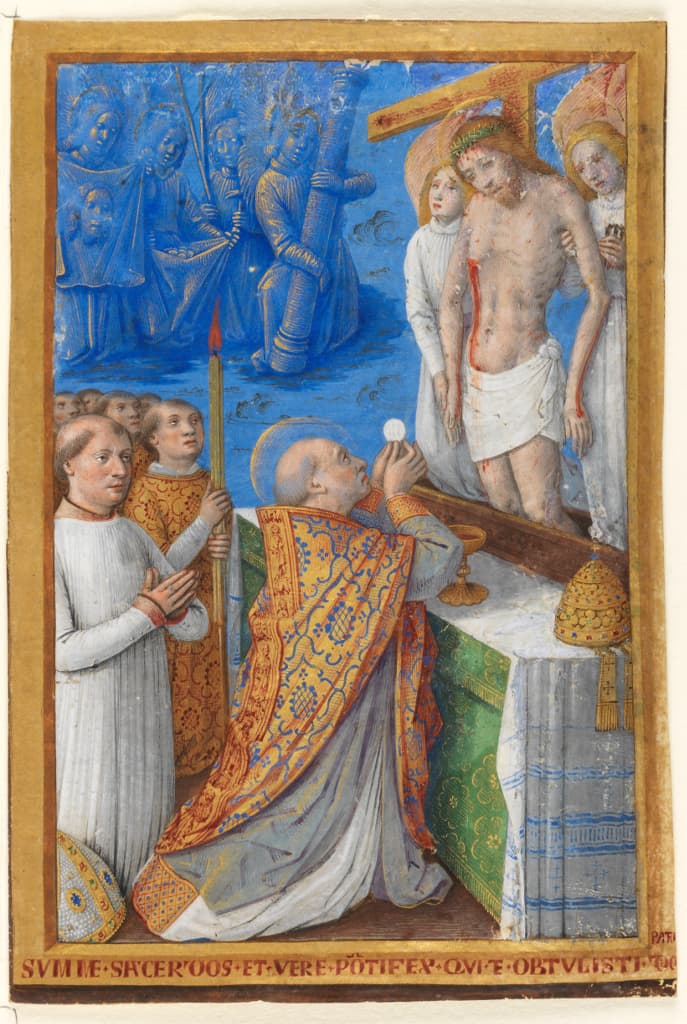

From the 2002 Missale Romanum

The name Actio is a forcible reminder that the Mass is not a matter of teaching but of doing. [5] As a character in John Henry Newman’s novel Loss and Gain eloquently puts it, the Mass

is not a mere form of words—it is a great action, the greatest action that can be on earth. It is, not the invocation merely, but, if I dare use the word, the evocation of the Eternal. He becomes present on the altar in flesh and blood, before whom angels bow and devils tremble. This is that awful event which is the scope, and is the interpretation, of every part of the solemnity. Words are necessary, but as means, not as ends; they are not mere addresses to the throne of grace, they are instruments of what is far higher, of consecration, of sacrifice. [6]

Note the reasoning: the entire Mass (even the Mass of the Catechumens) is an action comprised of words, but every action and every word are subordinated not to didactic goals but to the Action, the sacrifice on the altar. It is, as Newman writes, the scope and interpretation of every part of the solemnity. And that Newman calls this sacrifice “that awful event” (in the full sense of the word) supports the idea of calling the Canon the dangerous Lord’s Prayer, for the other Lord’s Prayer, the Pater noster, is powerful but not dangerous.

Intrat in Canonem

Infra Actionem is a rubric that remains but is seldom considered; let us now turn to a rubric that was lost centuries ago but presents a complementary theology. In the liturgical books of the Carolingian era for a Pontifical High Mass, one reads: surgit solus pontifex et tacite intrat in canonem (“The pontiff rises alone and enters silently into the Canon”). [7]

The rubric draws from a medieval tradition that the Canon is a Holy of Holies into which only the celebrant can enter. As Fr. Josef Jungmann summarizes (disapprovingly): “The priest alone is to enter this inmost sanctum, while the people stand praying without, as once they did when

Zachary burned incense in the Temple sanctuary.” [8] Fr. Daniel Cardo concurs but sees this imagery in a positive light:

It might be possible to recognize in the expression intrat in canonem a symbolic meaning indicating that the priest is, at that point, crossing the threshold of the holy of holies, where the veil of the true temple of Christ’s body was torn (cf. Matt. 27, 51): his side opened on the Cross, from where the Church receives the gift of the sacraments. [9]

Moreover, there is a fascinating metaphysics underlying this abandoned rubric. The Mass began with the priest declaring that he will enter into the altar of God (Introibo ad altare Dei) before he ascends the steps to the altar and prays the Aufer a nobis about entering the Holy of Holies. At this point of the Mass, the Holy of Holies is conceived of spatially, as one would expect of a temple; to enter into one part, one must physically move into it. But with this medieval rubric at the beginning of the Canon, the Holy of Holies is not conceived of spatially: the priest has already been standing at the altar for some time. Here, to enter into the Holy of Holies, he does not relocate from A to B but transitions from potency to act. The Holy of Holies is no longer the greatest place on earth but the greatest action that can be on earth.

Notes

[1] Epistle 2, ad Eutherium vel Profuturum.

[2] See Adrian Fortescue, The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy (Longmans, Green, and Co, 1912), 323-24.

[3] See the Penitential of Cummian 13.21; B. MacCarthy, “On the Stowe Missal” in The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, vol. 27, Polite Literature and Antiquities (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1877), pp. 135-268, esp. 163-64 and 186-87.

[4] William Durandus uses the phrase infra actionem when speaking of any addition to the Canon, such as when Pope Leo the Great added the prayer Hanc Igitur. (see Rationale Officiorum Divinorum IV.39.4)

[6] John Henry Newman, Loss and Gain: The Story of a Convert (London: Burns & Oates, 1962), 185.

[7] Ordo Romanus II.10.

[8] Josef Jungmann, S.J., The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development, vol. 1 (Benzinger Brothers, 1951), 82-83. For Jungmann, who operated out of a hermeneutics of rupture, this concept is another lamentable example of the liturgy’s clericalization, a break from the allegedly more communal liturgy of the primitive Church.

[9] Daniel Cardó, The Cross and the Eucharist in Early Christianity: A Theological and Liturgical Investigation (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 110-11.