Lost in Translation #131For practical reasons the Sanctus is considered its own composition, but as Adrian Fortescue writes, it “is, of course, merely the continuation of the Preface. It would be quite logical,” he continues,

if the celebrant sang it straight on himself. But the dramatic touch of letting the people fill in the choral chant of the angels, in which (as the preface says) we also wish to join, is an obvious idea, a very early one and quite universal. [1]

Early indeed. The liturgical

Sanctus is testified by Clement of Rome (d. ca. 100) and Tertullian (155-220), and some version of it is found in all apostolic liturgies. In the Antiochene, Roman, Ambrosian, Gallican, and Mozarabic Rites, the trisagion of Isaiah 6,3 is followed by the Palm Sunday proclamation of the crowd in the Gospels. [2] In the Roman Rite the result is the following:

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus, Dóminus Deus Sábaoth. Pleni sunt cæli et terra glória tua. Hosánna in excélsis. Benedíctus qui venit in nómine Dómini. Hosánna in excélsis.

Which is usually translated as:

Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God of Sabaoth. Heaven and earth are full of Thy glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is He that cometh in the Name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.

In Isaiah 6, the prophet sees the Lord sitting on a throne high and elevated, with His train filling the temple. Two six-winged Seraphim use two of their wings to cover the Lord’s face, two to cover His feet, and two to fly. As they do so, they sing to each other: “Holy, holy, holy, the Lord God of hosts, all the earth is full of his glory.”

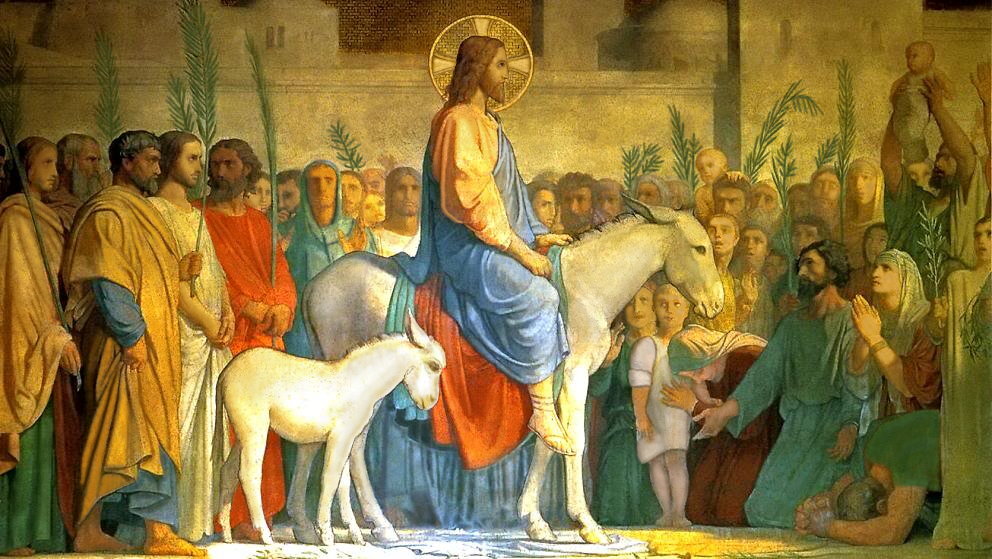

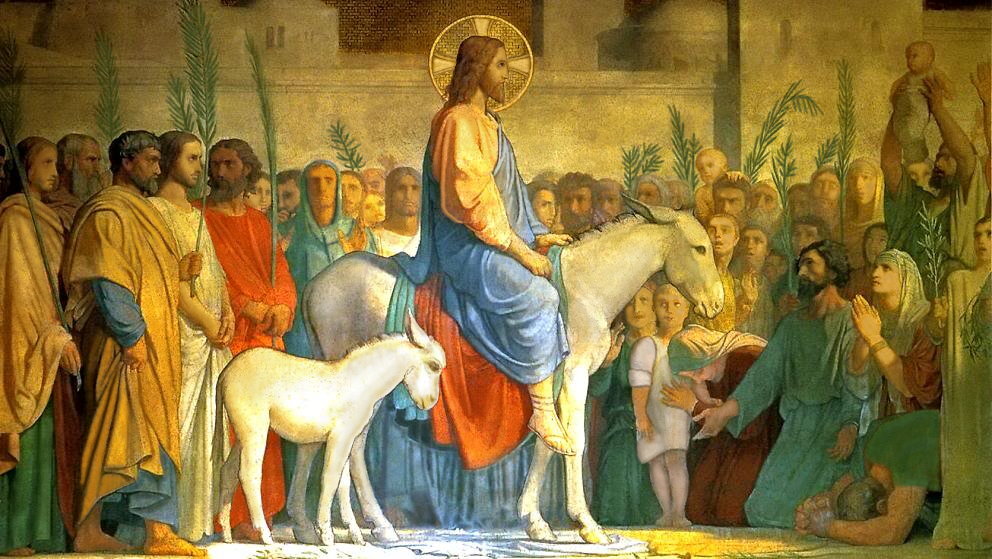

In the Gospel according to St. Matthew, when Jesus enters Jerusalem on Palm Sunday on the back of a donkey, the crowd proclaims: “Hosanna to the son of David: Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord: Hosanna in the highest.” (Matt. 21, 9) The other Gospels give similar accounts, (see Mk. 11, 9, Lk. 19, 38, and Jn. 12, 13) but no Evangelist has exactly the same wording as the liturgical formula.

While the triple Sanctus has obvious Trinitarian implications, the pairing of the two texts leads one to a consideration of the Incarnation. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, “The people devotedly praise the divinity of Christ with the Angels, saying Sanctus Sanctus Sanctus, and His humanity with the [Hebrew] children, saying Benedictus qui venit.” [3] This interpretation is corroborated by the gestures of the priest. During the Sanctus he is bowed down in adoration, and at the Benedictus he stands aright and makes the sign of the cross—and the cross is the reason that the Word became flesh. In this respect, the entire Sanctus hymn is like the sign of the cross, which expresses the two great mysteries of the Christian Faith, the Trinity and our Redemption.

Hosanna

There are two linguistic curiosities in this hymn, the use of the Hebrew loan words Sabaoth and Hosanna.

The word Hosanna is an abbreviation of hōshī‘ā nā’, which means “save, now!” (see Ps. 117 [118], 25) The word played an important role in the Hebrew Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot); it was recited by the priest every day when he processed around the altar, and it was recited seven times on the seventh day, once during each of the seven processions. When the priest came to the word Hosanna, the people would say it with him as they waved their branches of palm, willow, etc. Indeed, the seventh day of the feast was named the Great Hosanna, and the branches were called hosannas. [4]

One can understand, then, why Saints Matthew, Mark, and John describe the people shouting Hosanna and carrying palm branches during Our Lord’s entry into Jerusalem. Among other things, their actions were an affirmation of Jesus as the One who saves now.

And one can understand why the word remains untranslated in Christian liturgy, a tradition that stretches back to the time of the Apostles (it is mentioned in the first-century Didache). First, it connects the assembled faithful who utter it soon before the sacrifice of the altar to the disciples who uttered it soon before the sacrifice of the Cross.

And second, the word is complex: its denotation is plaintive, suppliant, and urgent, but its connotation is boisterous and joyful (as we see in the way that it is used). “Hosanna is the voice of one imploring, showing emotion more than signifying something, like what they call interjections in the Latin language.” [5] But if Hosanna communicates more of a feeling than a meaning, it may be more difficult to translate. The German language, for example, captures quite nicely the essence of schadenfreude, as does the Italian la dolce vita; to use German for the latter and Italian for the former would be an abomination. And it is common for people speaking a second language to revert to their native tongue for exclamations or interjections. Hosanna, then, contains a certain Hebrew-Messianic je ne sais quoi that the new people of God are able to channel.

Sabaoth

Less obvious is the retention of Sabaoth. Unlike Hosanna (or, for that matter, Alleluia and Amen), there would seem to be no ineluctable qualities to the word. Sabaoth is simply the Hebrew for hosts or armies, and thus it can easily be translated into Greek or Latin--indeed, the Vulgate translates Sabaoth as exercituum without any trouble and the Douay Rheims follows suit with “of hosts.” And yet in the Septuagint, the authors chose to leave the word untranslated in Isaiah 6, 3:

ἅγιος ἅγιος ἅγιος κύριος σαβαωθ πλήρης πᾶσα ἡ γῆ τῆς δόξης αὐτοῦ.

Or:

Holy, holy, holy, the Lord God of Sabaoth, all the earth is full of his glory.

In fact, the Septuagint retains the Hebrew Sabaoth sixty-one times.

But if the meaning of the word is clear, its referent is not. The armies in question could be those of ancient Israel, rallying under their divine commander-in-chief; they could be the Angelic hosts of all nine orders; and they could even be the stars. (see Gen. 2, 1) Whichever it is, the expression made its way into the Christian lexicon. Both Saints Paul and James refer to God as the Lord of Sabaoth in their Epistles, (Rom. 9, 29 and James 5, 4) and it also made its way into the sacred liturgy, probably from almost the beginning. In his letter to the Corinthians, Pope St. Clement of Rome cites Isaiah 6, 3 with the word Sabaoth in what is most likely a liturgical context. [6] In any case, all the ancient liturgies, Eastern and Western, have Sabaoth in their Sanctus hymn. [7]

The Latin edition of the new Roman Missal (1970/2002) likewise retains this ancient word, but the translations of it are another matter. While the German edition has Zebaoth, the French, Italian, and Spanish have “God of the universe” (Dieu de l’univers, Dio dell’universo, and Dios del Universo, resp.). In English, the 2011 translation replaced the 1970’s “God of power and might” with “Lord God of hosts.” The same translations, incidentally, all retain the word Hosanna.

One wonders what, if anything, is lost by translating Sabaoth into the mother tongue. Pius Parsch claims that the words Hosanna and Sabaoth “have come down to us from the primitive Church of Palestine, and were not translated, because a peculiar meaning had in the course of time become associated with these words;” [8] and yet he neglects to tell us what the peculiar meaning of Sabaoth is. I suspect that like Hosanna, it may be more of a feeling than a meaning, in this case, the feeling one gets when encountering the numinous, a feeling of awe and dread. The sight of a vast army is no doubt terrifying, but the Lord’s armies come with inscrutable supernatural powers that make our conventional weapons look harmless. Sabaoth, in other words, conjures up an awareness of the unknown and awful (in the full sense of the word) powers of an omnipotent God: indeed, when Revelation seeks a substitute for Sabaoth, it uses “almighty.” (Rev. 4, 8) [9] Removing Sabaoth from the liturgy, then, contributes ever so slightly to an evacuation of the numinous from the sacred.

Notes

[1] Fortescue, The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy (Longmans, Green, and Co, 1912), 320-21.

[2] Fortescue, 321-22.

[3] Summa Theologiae III.83.4.

[5] Hosanna vox est obsecrantis, magis affectum indicans quam rem aliquam significans, sicut sunt in lingua Latina quas interjectiones vocant. (Attributed to Saint Augustine. See St. Thomas Aquinas, Catena aurea in Johannem 12.2.29).

[6] 1 Cor. 34, 6-7.

[7] Fortescue, 321-22.

[8] The Liturgy of the Mass, trans. Frederic C. Eckhoff (St. Louis, Missouri: Herder, 1940), 219.

[9] William Durandus emphasizes omnipotence in his interpretation of Sabaoth. (see Rationale Divinorum Officiorum IV. 34, 6) Further, I believe that both Saints Paul and James use “Lord of Sabaoth” because it triggers a slight fear of God in the reader. The former, quoting Isaiah, includes the epithet in a sentence about the judgment of Sodom and Gomorrah while the latter writes of the cries of exploited and oppressed workers entering into the ears of a presumably outraged Lord of Sabaoth.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)