After praying the Suscipe Sancta Trinitas, the priest kisses the altar and turns clockwise towards the people, saying Orate fratres while opening and closing his hands. He completes the prayer as he continues his clockwise movement, finishing both at the same time. When he is done, the prayer Suscipiat is said.

The Orate fratres is:

Oráte, fratres, ut meum ac vestrum sacrificium acceptábile fiat apud Deum Patrem omnipotentem.Which is commonly translated as:

Brethren, pray that my Sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the Father almighty.The Suscipiat is:

Suscipiat Dóminus sacrificium de mánibus tuis, ad laudem et gloriam nóminis sui, ad utilitátem quoque nostram, totiusque Ecclesiae suae sanctae.Which is commonly translated as:

May the Lord receive the Sacrifice from thy hands, for the praise and glory of His name, for our benefit and that of all His holy Church.Adrian Fortescue and other rubricists identify three tones of voice at a Low Mass: aloud, audible but low, and “silent” (at a whisper). At a Low Mass, the priest says the two words Orate fratres aloud while the rest is said audibly but lowly. Although not in the rubrics, it is customary for the priest to say the last word of the prayer, omnipotentem, somewhat more loudly so that his respondent(s) knows when to begin the Suscipiat. [1]

Who says the Suscipiat in reply depends on the kind of Mass being offered. At a Solemn High, the deacon does it; if he has not returned to his position in time, the subdeacon says the prayer for him. At a Missa cantata or sung Mass, if there is an MC, he says it; if there is not and there are only two servers, they say it. At a low Mass, the Suscipiat is said by the server(s) and/or congregation. If there is one server and for some reason he cannot answer, or if there is no server and the priest is alone, the priest says the Suscipiat himself, changing “thy hands” (de manibus tuis) to “my hands” (de manibus meis).

The Orate frates is said or used differently on Good Friday and during a Missa coram Sanctissimo, a Mass during which the Blessed Sacrament is exposed on the altar. On Good Friday, after finishing the In spiritu humilitatis (not the Suscipe Sancta Trinitas), the priest kisses the altar, genuflects, turns counterclockwise towards the Gospel side, says Orate fratres, and turns back the same way with no answer made. At a Missa coram Sanctissimo, since it would be rude to turn one’s back on one’s Lord and King, the priest turns clockwise as usual but does not complete the circle; rather, he returns counterclockwise to the altar, as he does at the Dominus vobiscum. [3]

The circular—or rather, semicircular—motion of the priest is distinctive. Usually, when the priest faces the people to make a declaration such as Dominus vobiscum, he returns whence he came, as if powered by a spring that stretches him out and brings him back again. But with the Orate fratres, the priest crosses the meridian and never returns. The only other time that this action happens is after the dismissal (Ite, missa est) and before the Last Gospel. If you consider anything that happens after the dismissal an epilogue of the Mass rather than part of the Mass per se, then the semicircular motion of the Orate fratres is unique within the Mass.

In terms of diction, we call attention to three aspects of these prayers:

First, meum ac vestrum. Had the Holy Spirit been lazy or in a hurry, He could have said, nostrum sacrificium or “our sacrifice” instead of “your sacrifice and mine.” The original ICEL translators chose this route (despite the obvious meaning of the Latin), but their decision was rejected in the new official English translation in 2011. What is the difference, and why does it matter?

The original wording calls attention to the common yet differentiated priesthood of all believers which, it is alleged, the 1970s ICEL translation blurs and buries intentionally. As a validly ordained minister, the priest has the faculty to offer the Sacrifice of the Mass, to turn bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. In that respect the sacrifice is his and his alone, one for which he himself has sacrificed much (with vows of celibacy, obedience, etc.).

But Catholics also comprise a “royal priesthood” by virtue of their baptism (see Exodus 19, 6; 1 Peter 2, 9) They too, when assisting at Mass, offer the Mass in their own way. Other Western rites (e.g., the Mozarabic) and various usages of the Roman Rite (e.g., that of Cologne) make this facet clear when they add pariterque to the Orate fratres, as in ut meum sacrificum pariterque vestrum. Pariterque means “and equally,” but we can also translate it as: “May my sacrifice, and every bit as much as well yours, be…” Keeping to its signature economy with words, the Roman Rite lacks this added formulation, but the sentiment is still there. Even though they are not essential to the confection of the Eucharist, the laity help offer the sacrifice all the same.

My sacrifice, and yours

Second, sacrificium. What or which sacrifice is being referenced? As we have seen in previous articles, the Offertory Rite in Apostolic liturgical tradition, both East and West, is rightly understood as no mere preparation of the gifts, but as the first stage of the Holy Eucharistic Sacrifice and as a proleptic of that Sacrifice. (see here and here and here) And so we may wonder if the sacrifice in question is the sacrifice that has been offered so far, or the sacrifice that will be offered soon during the Canon. Sages from our tradition, such as Fr. Martin von Cochem (1630–1712) and St. Leonard of Port Maurice (1676–1751), interpret the sacrifice to be that which is to come through transubstantiation. Of course they are right, for there is only sacrifice of the Mass, which consists of the transformation of glutinous and vinicultural earthly matter into the divine Flesh of Our Lord. But given the importance imposed upon the laity to be present during the Offertory Rite (if they miss it, they have not “attended Mass” or fulfilled their Sunday obligation), it would be reductionistic to think of the “sacrifice” at this point of the Mass as something in the future and nothing more. The priest’s sacrifice and ours, when the Orate fratres is uttered, has already begun and is on the way to its numinous crescendo.

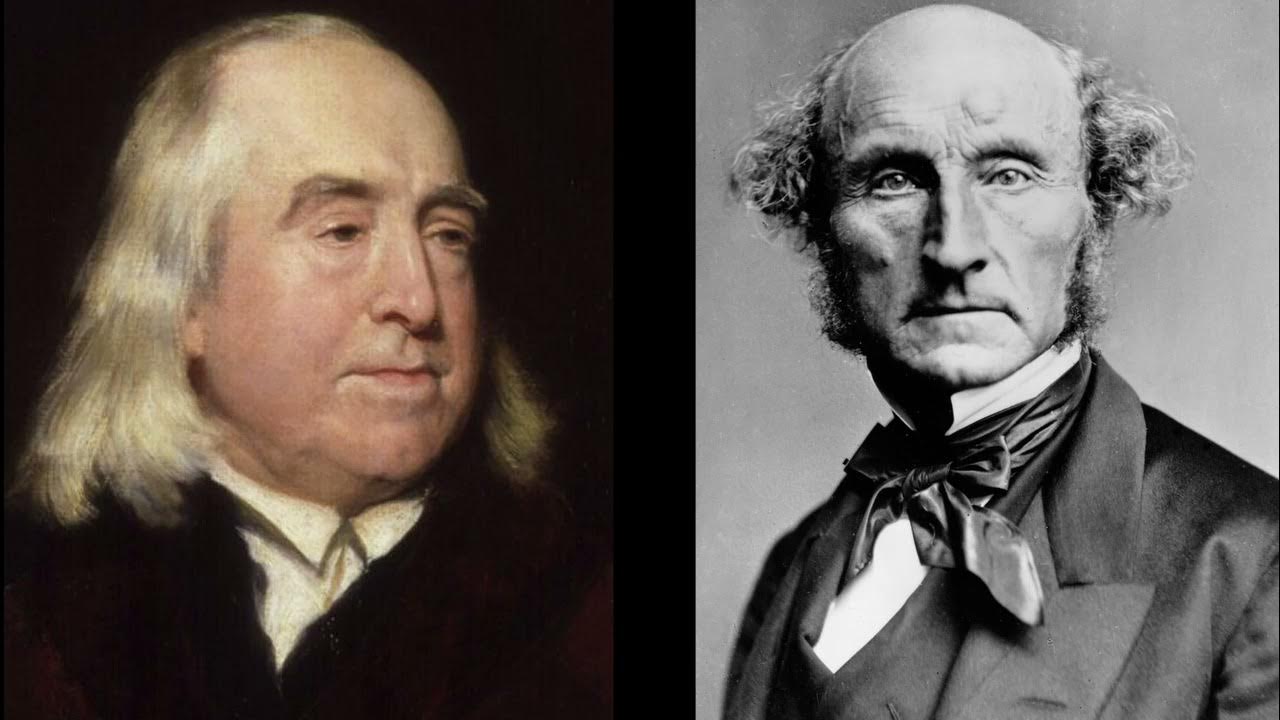

Third, utilitatem. English translations overwhelmingly favor “benefit” as the correct equivalent, and they are prudent in their judgment. At first blush “utility” is the more obvious choice, but the problem is that the Anglophonic well has been poisoned by the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which privileges anything useful in the hedonistic attainment of happiness, even, perhaps, flagrant acts of injustice. The use of utilitas in this prayer, on the other hand, calls to mind the classic Augustinian distinction between use (utor) and enjoyment (fruor). For Augustine, God alone is that which is to be enjoyed, and the useful is that which (in accordance with His law, of course) is that which is made use of in light of that enjoyment. Whereas nineteenth-century utilitarianism tries to claw its way up to happiness from the bottom up (looking to everything and anything utilitarian that will help it along the way), Augustinian theology looks at life from the top down, seized by the love and enjoyment of God that puts all of His temporal goods in their true (and useful) perspective.

Bentham and Mill: do they look happy to you?

One sees this celestial, as opposed to grungy, perspective in the Suscipiat. The Sacrifice is first and foremost for the praise and glory of God’s name, come what may, and only secondarily is it for our benefit. That “secondarily” is reinforced by the addition of quoque (also) in the prayer, which is rarely if ever translated although it should be. It is as if the Suscipiat is saying: “May God be glorified for His own sake (enjoyment). Oh, and yeah, also for our benefit (use), which in the rapture of love only comes to mind as an afterthought.”

Notes

[1] Ceremonies of the Roman Rite, 41.

[2] 299.

[3] 61-62.