Lost in Translation #141

To turn a mixture of wine and water into the Blood of the Son of Man, the priest prays:

Símili modo postquam cenátum est, accipiens et hunc praeclárum cálicem in sanctas ac venerábiles manus suas: item tibi gratias agens, benedixit, deditque discípulis suis, dicens: Accípite, et bíbite ex eo omnes.Hic est enim Calix Sánguinis mei, novi et aeterni testamenti: mysterium fídei: qui pro vobis et pro multis effundétur in remissiónem peccatórum.Haec quotiescumque fecéritis, in mei memoriam faciétis.

Which I translate as:

In a similar way, after dinner, taking also this excellent chalice into His holy and venerable hands, again giving You thanks, He blessed it and gave it to His disciples saying: Take and drink from this, all of you.For this is the Chalice of My Blood, of the new and everlasting covenant, the Mystery of Faith; which shall be poured forth for you and for many for the remission of sins.As often as you do these things, you shall do them in memory of Me.

Today, we will examine the biblical background behind this prayer; next week, we will examine the Roman Canon’s modifications.

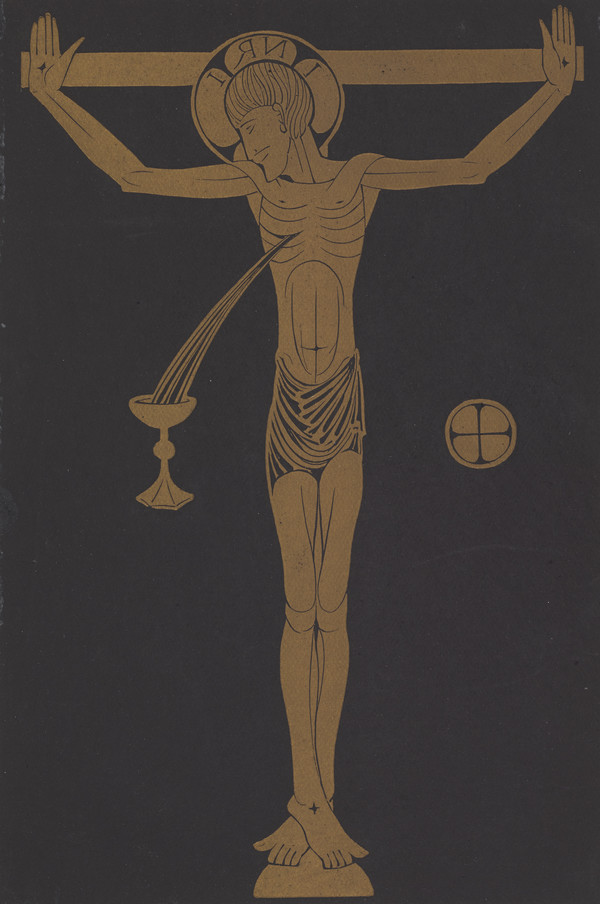

The Words of Institution for the Precious Blood in the New Testament are more peculiar than those for Our Lody’s Body. The Gospels according to Matthew and Mark have a straightforward formula: Hic est enim sanguis meus novi testamenti—“For this is My blood of the New Covenant” (Matt. 26, 28; see Mark 14, 24). But Luke’s Gospel and Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians have: “This chalice is the New Covenant in My Blood” (Luke 22, 20; see 1 Cor. 11, 25). The statement is sufficient for transubstantiation, but it is less direct; moreover, it draws attention to that which holds the Precious Blood, a manmade chalice, while there is no corresponding artifact of importance associated with the Host. (It rests at various times on the corporal and the paten, but neither is mentioned in the prayers). The Roman Canon follows the Lucan-Pauline tradition, although it also retains the word enim from Matthew’s account of the Last Supper (or perhaps it is a coincidence). St. Thomas Aquinas defends the formula Hic est enim Calix Sanguinis mei by arguing that the chalice is either a metonymy for Christ’s Blood or a reference to His Passion, for He referred to His Passion as a chalice (see Matt. 26, 39) and it was by virtue of His Passion that His Blood was separated from His Body. [1]

The Roman Canon follows Saints Luke and Paul in two other respects. First, both authors state that the consecration of the wine happened in a similar manner to that of the bread. The Vulgate uses the adverb similiter to express this fact, while the Canon uses the adjectival phrase simili modo.

Second, Saints Luke and Paul and the Roman Canon stipulate that the consecration of the wine took place after dinner. The Vulgate uses a simple means of communicating this fact with postquam coenavit or “After he dined.” The Canon, on the other hand, uses the impersonal passive voice, a construction popular in several languages in which the verb essentially has no subject. (The closest equivalent in English is the use of “there,” as in “There are no bananas.”) If one wanted to assert in Latin that a dance was going on, one would say saltatur, or “it is being danced.” In the case of the Canon, the phrase postquam cenatum est is most slavishly translated “after it was dined” or “after dinner took place.” The 2011 ICEL translation captures the flavor of the impersonal passive with its “when supper was ended.” Preconciliar hand Missals, on the other hand, often drew from the Vulgate phrasing and had “after He had supped.”

All four New Testament accounts identify Christ’s Blood as the Blood of the New Covenant; they do not do the same for Christ’s Body. Biblically speaking, blood is the sine qua non for contracting a covenant; indeed, the Hebrew phrase for making a covenant is “to cut a covenant.” With the exception of circumcision, Old Testament covenants were made with a vicarious victim. Here, Christ offers His own blood as an everlasting covenant for the remission of our sins. The significance is at least threefold.

The first is ablution and aspersion, washing and sprinkling. The flesh of the sacrificial lamb may have been eaten during the feast of Passover, but its blood was sprinkled on the doorposts, thereby averting the Angel of death. Similarly, St. Peter speaks of being sanctified for “the sprinkling of the Blood of Jesus Christ,” (1 Pet. 1, 2) while the Book of Revelation describes the Blood of the Lamb of God as washing the white robes of the saints. (7, 14; cf. 1, 5)

Second, the red Blood that washes white also redeems, buying us back from the slave block of the devil. In the Epistle to the Hebrews we read that “neither by the blood of goats or of calves, but by His own blood [Christ] entered once into the Holies, having obtained eternal redemption.” (Heb. 9, 12) One of the earliest epithets for the Savior’s Blood in Church parlance is pretium redemptionis nostrae, the “price of our redemption.”

Third, we remember the Atonement, with its teaching on sin and propitiation. The Blood forcibly reminds us of our shared responsibility in spilling it, and God’s mercy in accepting it as our reconciliation with Him. In the Book of Genesis, the blood of Abel “speaks” from the ground. (4, 10) What does it say? That Cain is guilty. Similarly, the Epistle to the Hebrews states that the Blood of Christ “speaks better” than Abel’s. (12, 24) What does it say? That we are guilty, but that we are also reconciled. Christ was wounded for our iniquities, (Is. 53, 5) but it is by these stripes that we are healed. (1 Pet. 2, 24) Hence, God proposes His Son as “a propitiation, through faith in His blood…for the remission of former sins.” (Rom. 3, 25)

As a sidenote, the differing qualities of body and blood are why it is appropriate to have separate feasts honoring Christ’s Eucharistic Body and His Precious Blood. For although to receive one is to receive the other (thanks to concomitance), the connotations of each are different. When we think of the Host, we think of spiritual food and, as the Feast of Corpus Christi puts it, a “pledge of our future glory,” that is, our glorified bodies. But when we think of the Precious Blood, we think of immolation, sprinkling, redemption, atonements, etc.

All three Gospels accounts use the verb fundetur or effundetur for what happens to this Blood; the Roman Canon uses effundetur. Although some preconciliar hand Missals translate effundetur as “shed,” the 2011 ICEL translation’s “poured out” is more accurate, for the verb effundere means to pour forth, rather than to cut into something and make blood flow. It is a fitting choice for the Blood that Our Lord shed, for indeed it was poured out like a libation. According to tradition, Jesus Christ was exsanguinated during His Passion, pouring forth every drop of His blood for the sake of humanity—even posthumously, His slain side issued forth blood and water. And “pouring out” also describes the movement of wine, first into the chalice and then into the mouth of the recipient.

Finally, the New Testament accounts give different answers to the question for whom this Blood is poured out. Matthew and Mark state that it is pro multis (“for many”), while Luke states that it is pro vobis (“for you”). Paul is silent on the matter; instead he writes: hoc facite quotiescumque bibetis, in meam commemorationem (“As often as you do these things, you shall do them in memory of Me.”). The Roman Canon combines all three elements into a seamless whole.

The translation of pro multis was once the subject of controversy, since the original ICEL rendered it “for all” instead of “for many” (the 2011 translation corrected this). Although God does indeed want all to be saved, (see 1 Tim. 2, 4) the translation shows a certain haughty disregard for the original meaning and raised fears that the heresy of universalism was being encouraged. My own sense is that the pro multis is not meant to weigh in on what percentage of the population is going to Heaven or Hell; rather, it is a statement about the scope of this New and Everlasting Covenant that is being cut. The Mosaic covenant, for example, was for the few, the tiny nation of Israel; the Davidic covenant was for the one, David himself. The New Covenant, by contrast, is not for the one or for the few; it is for the many, for Jew and Gentile alike. [2]

Notes

[1] Summa Theologiae III.78.3.ad 1.

[2] See [1] Summa Theologiae III.78.3.ad 8: “The blood of Christ’s Passion has its efficacy not merely in the elect among the Jews, to whom the blood of the Old Testament was exhibited, but also in the Gentiles; nor only in priests who consecrate this sacrament, and in those others who partake of it; but likewise in those for whom it is offered. And therefore He says expressly, ‘for you,’ the Jews, ‘and for many,’ namely the Gentiles; or, ‘for you’ who eat of it, and ‘for many,’ for whom it is offered.”