Lost in Translation #143

The greatest surprise of all in the Roman Canon is the insertion of the words mysterium fidei into the Simili modo, for although it does not interrupt the consecration formula (“This is the Chalice of My Blood”), it does interrupt the scriptural narrative. The phrase was added inappropriately (inconvenienter), charges an objection in the Summa Theologiae. [1] Or in the words of Jungmann, “And then, in the middle of the sacred text, stand the enigmatic words so frequently discussed: mysterium fidei.” [2] And Parsch: “The insertion of ‘the mystery of faith’ is most unusual, since it even disturbs the construction of the sentence.” [3]

At least the words are scriptural. When speaking of ideal deacons, St. Paul writes that they should be “Holding the mystery of faith (mysterium fidei) in a pure conscience.” (1 Tim. 3, 9) Perhaps it is this ancient association of the mystery of faith with the diaconate that gave rise to the speculation that the deacon exclaimed the words mysterium fidei! during this consecration before the phrase was transferred to the Canon. The theory, however, is not generally accepted today. [4]

And since Latin lacks definite and indefinite articles, these two words are surprisingly difficult to translate. Is it “the mystery of faith” or “a mystery of faith”? Or is it “a/the mystery of the Faith”? It is not clear whether the faith in question is subjective (my assent to sacred dogma, fides qua creditur or the faith by which I believe) or objective (the content of the dogma – fides quae creditur, the Faith which is believed). For some medieval interpreters, it was the former: “the mystery completed in the Eucharist – the transubstantiation of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ – could be understood only by means of subjective faith.” [5] And it is also quite possible, given Patristic literature (as with the Eastern Orthodox today), that mysterium here means not mystery but sacrament, and thus the phrase could be translated, “a sacrament of the Faith.” “The interpolation mysterium fidei would imply that the Eucharist contains all the mysteries of Christ,” writes Abbot Barthe. “It is ‘the mystery of faith,’ the sacrament par excellence.’” [6]

The phrase’s referent also poses challenges. Mysterium fidei is an appositive of calix or chalice. An appositive, if you recall, is a noun phrase placed close to another noun or noun phrase to create an identity between the two. In the sentence, “George, the mailman, walked down the street,” “George” and the “mailman” are one and the same. In this prayer, the Chalice and the mysterium fidei are one and the same. Again the possibilities are manifold. “This is my Chalice, a mystery of faith.” “This is my Chalice, a sacrament of faith.” “This is My chalice, the mystery of our Faith.” Etc.

For St. Thomas, all the additions after “This is the chalice of My Blood” signify the power of the Blood shed during the Passion: “eternal” shows its power in securing our eternal heritage; and “which will be poured forth for you…” shows its power to forgive sins. As for the “mystery of faith,” Aquinas writes, the phrase is there to signify the

justification of grace, which is through faith, according to Romans 3, 25-26: “Whom God hath proposed to be a propitiation, through faith in His blood . . . that He Himself may be just, and the justifier of him who is of the faith of Jesus Christ.” [7]

Aquinas also notes that the word “mystery” is a reminder that the reality of the sacrament is present but hidden. [8]

Structure

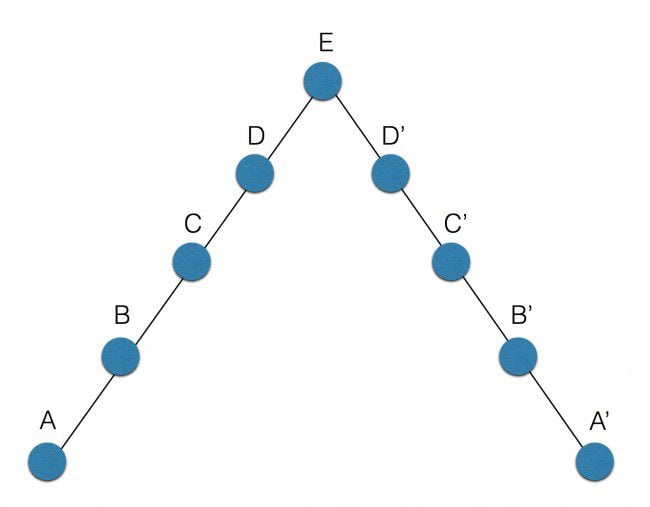

Stepping outside our linguistic questions for a moment, we note the ingenious placement of the mysterium fidei. The phrase is in the exact center of the sentence Hic est enim Calix Sánguinis mei, novi et aeterni testamenti: mysterium fídei: qui pro vobis et pro multis effundétur in remissiónem peccatórum. Ten words are before it, and ten words are after it. There is a way in which, then, mysterium fidei is at the center of the entire Canon, with the two halves forming a chiasm or chiasmus around it. A chiasm follows a pattern like CBAABC or:

Or in the case of the Canon:

Matthew Gerlach sees this pattern in terms of a moving helix: [10]

Literally at the apex of our worship, then, lies the Mystery of Faith.

Postscript

Or did. Following upon the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas and others, Nicholas Gihr places great confidence in the providence of liturgical development:

These additions of the liturgy have emanated from a divine and apostolic tradition and are, therefore, as incontestably true and certain as are the words of the inspired authors [of the Bible]. [10]

But the architects of the Novus Ordo did not place the sacred liturgy on the same level as the Sacred Scriptures. When the Roman Canon was retained only because of the insistence of Pope Paul VI (Bugnini wanted to omit it entirely), the

mysterium fidei was plucked from its central place and used as a prompt for the people to make a “

memorial acclamation,” possibly in imitation of the uncertain hypothesis that the phrase was originally said by the deacon. [11] Decades later, Vatican II peritus Alphonse Cardinal Stickler would express

consternation at this innovation. After noting that all records indicate that

mysterium fidei has been a part of the Roman Rite from the very beginning and that therefore there is no historical warrant for making this “quite serious change in the consecration formula,” he concludes:

For this reason, the banishing of mysterium fidei from the Eucharistic formula becomes a powerful symbol of demythologization, a symbol of the humanizing of the center of divine worship, of holy Mass.

Notes

[1] Summa Theologiae III.78.3.ob 5.

[2] Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 2, 199.

[3] Parsch, 236.

[4] Jungmann, vol. 2, 199.

[5] Michael Fiedrowicz, The Traditional Mass, 279.

[6] Barthe, Forest of Symbols, 112.

[7] Summa Theologiae III.78.3.

[8] Summa Theologiae III.78.3.ad 5.

[9] Matthew Thomas Gerlach, Lex Orandi, Lex Legendi: A Correlation of the Roman Canon and the Fourfold Sense of Scripture (2009 dissertation thesis, Marquette University).

[10] Gihr, Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, 634.

[11], For the full story, see Peter Kwasniewski’s chapter on the subject in his Once and Future Roman Rite.