Lost in Translation #130

The 1962 Missal contains twenty Prefaces (including the five so-called Gallican Prefaces added by Pope St. John XXIII in November of that year), but it may be more accurate to say with Abbé Claude Barthe that the Roman Rite has one Preface with twenty different options, just as there is one Roman Canon with different versions of the Communicantes and Hanc Igitur. [1]

The Opening

The opening of the Preface is almost always the same:

Vere dignum et justum est, aequum et salutáre, nos tibi semper et ubíque gratias ágere, Dómine sancte, Pater omnípotens, ætérne Deus:

Which I translate as:

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, that we should at all times and in all places, give thanks unto Thee, O holy Lord, Father almighty, everlasting God;

The two exceptions are the Preface for Easter and the Preface for the Apostles or Evangelists. The former bespeaks the sheer exuberance of Paschaltide:

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, that at all times, but more especially on this day [or in this season], we should extol your glory, Lord, when Christ our Pasch was sacrificed:

The Preface for the Apostles is more unusual in that it addresses God the Son rather than God the Father:

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, to pray humbly to You, O Lord, eternal Shepherd, not to desert Your flock but to keep it in continual protection through Your blessed Apostles…

Together all the Prefaces declare that giving thanks to God everywhere and always, that extolling God’s glory, and that humbly praying to God have four qualities in common: they are dignum et justum, aequum et salutare. Since we discussed dignum et justum last week, let us now turn to aequum et salutare.

Aequus, which is etymologically related to “equality” and “equity,” originally referred to an area that was level or even, and because it was level or even (as opposed to steep or bumpy), it was considered favorable or advantageous. Applying this notion to the realm of morality, to be aequus was to be even-handed, fair, equitable, and impartial. From this understanding there developed the formula aequum est plus an infinitive verb, the meaning of which is “it is reasonable, proper, right, etc.” [2]

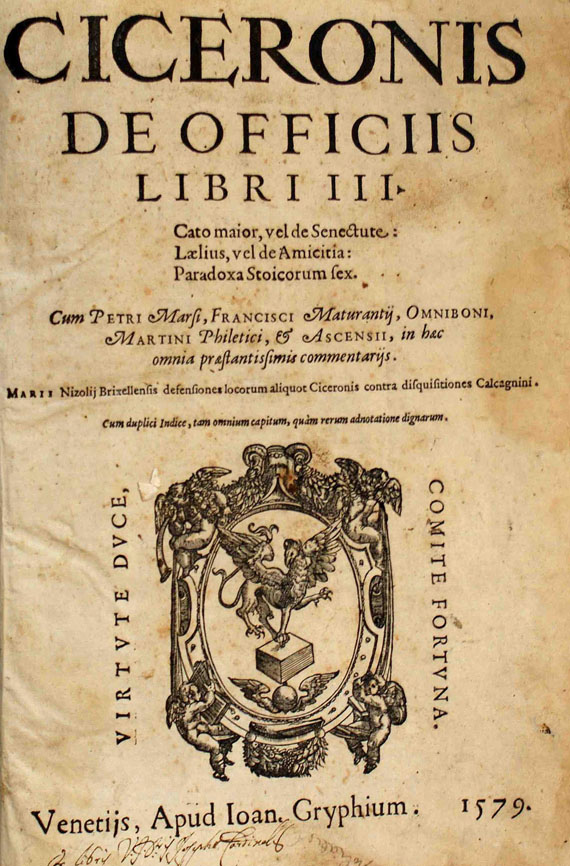

It seems that the claim of the Preface is that giving thanks to God is both morally correct and very much to our advantage. Of course, one can argue that the two are one and the same: to be just is to act to one’s true advantage and vice versa. Such is the thesis of Cicero’s classic De officiis, with which Catholic moral theology is in agreement. Nevertheless, the two ideas are distinct. It seems to me that the Preface uses two words to denote advantageousness and two words to denote moral correctness, and that it arranges these words chiastically:

To say that giving thanks to God is dignum is to say that it is worth our while; and to say that it is salutare is to say, as several preconciliar hand missals do, that it is “profitable for our salvation.” These concepts of advantage appeal to our enlightened self-interest, if you will.

Justum, on the other hand, clearly invokes justice, and I believe aequum plays a similar role in affirming the moral rectitude of thanksgiving. I therefore side again with the preconciliar hand missals when they translate aequum as “right.” The new Missal’s 2011 English translation of aequum also acknowledges the moral connotation of aequum here, but I believe it goes too far by translating it as “our duty,” for not everything that is right is a duty (it may be right for me to have a glass of wine with dinner, but it is not a duty). Similarly, I contend that the new translation of salutare as “our salvation” goes too far, for our salvation and something that contributes to our salvation are not the same thing.

The Ending

The majority of Prefaces end with sine fine dicentes (“saying without end”) while six, including the Gallican Preface for All Saints’ Day, end with supplici confessione dicentes (“saying with suppliant confession”). Only one, the Preface for the Holy Trinity, ends with una voce dicentes (“saying with one voice”), but since this Preface is used during the Time after Epiphany and the Time after Pentecost, it is the one heard the most by the average Latin Mass goer.

It is curious that the Preface, which was composed to be sung and which sometimes includes images of the congregation and the Angels singing together, ends with dicentes, speaking or saying. It is a reminder that the Latin verb dico can also mean “To describe, relate, sing, celebrate in writing.” [3] This usage is mostly found in poetry, which fits the lyrical quality of the Preface.

Claude-Marie Dubufe, La Suppliante, 1829

Of the various endings, supplici confessione dicentes, which I have slavishly rendered “saying with suppliant confession,” is the most difficult to translate. Most preconciliar hand missals have “with lowly praise” while the 2011 English translation of the new Missal has “in humble praise.” “Praise” is not wrong, but it is incomplete. For the early Church, confessio meant three things: praise of God, accusation of self, and profession of faith. There is, then, a slightly dolorous note to confessio insofar as it involves a recollection of our sinfulness, and this dolorous note, I believe, is reinforced by the adjective supplex: from sup-plico, bending the knees.

On the other hand, the dolorous note may not be the dominant one since supplici confessione dicentes is used on joyful occasions such as the feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of Saint Joseph, and it is also found in the Common Preface. The phrase is not found in the Preface for the Dead (where one might expect it), but it is found in the Preface for Lent and the Preface for the Holy Cross, which is used during Passiontide. Liturgical context may therefore be the deciding factor as to which meaning of confessio should be in the foreground. For instance, on a feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it may be more proper to translate confessio as “praise,” while during the season of Lent it may be more proper to translate it as “confession.”

Notes

[1] Claude Barthe, Forest of Symbols: The Traditional Mass and Its Meaning, trans. David J. Critchley (Angelico Press, 2023), pp. 97-98.

[2] Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary (Clarendon Press, 1879), “aequus,” II.B.3, p. 58.

[3] Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary, “2. dico,” I.B.4, p. 571.

[4] The Roman Missal, 3rd edition (USCCB Publishing, 2011), p. 552.