Following up on Thursday’s post about the church of St Christina at Bolsena, here are Nicola’s pictures of the catacomb next door to it, which was used for Christian burials in the fourth and fifth centuries. Like most catacombs, it has been largely stripped of the decorations and inscriptions that would have filled it in antiquity, and many of the remaining marble plaques are broken. As we saw on Thursday, the relics of St Christina are now in the main church; they were formerly kept in this sarcophagus with an effigy of her, which is set up in this grotto. Below it is the 4th century sarcophagus in which she was originally buried.

Sunday, July 27, 2025

The Catacomb of St Christina at Bolsena

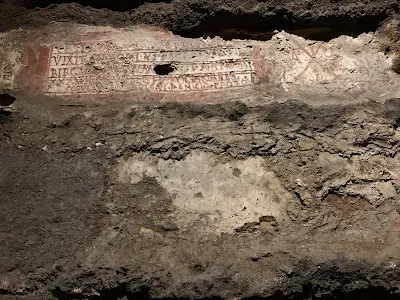

Gregory DiPippoThe majority of catacomb burials are slots in the walls of the corridors called “loculi – little places”, which were sealed with plaster, brick or plaques of marble. Marble was, of course, much the most expensive of these materials, but broken scraps of it could easily be obtained from the places where it was worked, much as one now acquires wood scraps from a lumber-yard. Inscriptions could be carved into the marble or plaster, or painted on the bricks, although this last procedure was rare.

Acting on the mistaken belief that the early Christians were subject to constant persecution from the Romans, and that therefore, most of them died as martyrs, modern archeologists opened up the graves while exploring them. In most cases, the graves were empty, apart from bits of bone dust, especially in the shallower parts of the catacombs, where there was more moisture to hasten decomposition. Where substantial portions of bone were found, they were brought to churches all over the world to be venerated as relics. (St Philomena, who was found in the catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, is a particularly famous example of this.)

Because scrap marble was readily available, it is not uncommon to see very low-quality inscriptions on this higher quality material.

Christian funeral inscription generally tend to record the name of the deceased, personal details, often in relationship to the person who had the inscription made (“Marcus made this for his wife Aurelia.”), and the date of their death, but almost never indicate the year in which they died. However, the date of the graves can often be determined by the lettering type of the higher-quality inscriptions, since it will be known that certain types are used in specific periods.

Many catacombs also have sarcophagi in them, whole or fragmentary, with scenes from pagan mythology. The explanation of this is that they were acquired by the persons who were buried in them before they converted to Christianity, and were simply to expensive to just not use after converting.

In later periods (roughly 6th to 8th), some parts of the catacombs were broadened and decorated so that Mass could be celebrated in them, not on a regular basis, but on the feasts of the martyrs whose remains were buried there. Here are some fragments of decorations added later to the catacomb.

A fresco on a grave with either a portrait of the deceased, or of St Christina.

A very rare example of an inscription painted on plaster.