Last November, we published a research project by Mr Nico Fassino on the 1954 English Rituale. He has now graciously shared with us a new project, this time on the history of the revival of Gothic vestments, which will be published here in three parts. Mr Fassino is the founder of the Hand Missal History Project, an independent research initiative dedicated to exploring Catholic history through the untold and forgotten experiences of the laity across the centuries. Learn more at HandMissalHistory.com or @HandMissals. Once again, we are very grateful to him for sharing his interesting and thoroughly well-researched work with us.

I recently saw a question about the modern history of ‘Gothic’ style vestments in the Roman Catholic Church. How and when were they re-introduced? At what point were they fully authorized for widespread use?

I am not an expert on vestments and have never studied their history. I was only casually familiar with what I would call the “common” narrative: that Gothic style vestments were illicitly adopted by some members of the Liturgical Movement in the early 1900s, forbidden as an abuse by Roman authorities, and only authorized in 1957 after which they became increasingly popular.

I was curious. Was this an accurate account or was there more to the story? I decided to explore historic Catholic newspapers and other contemporary material to see what I could find.

English Revival: Origins & Debate

The modern history of Gothic vestments largely begins with Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-52), at least for English-speaking lands. Pugin was a convert to Catholicism and an extraordinarily prolific ecclesiastical designer and architect. It is impossible to overstate his role or influence in launching the Gothic Revival movement.

|

| Augustus Welby Pugin, by John Rogers Herbert, 1845 (source) |

Bishop Thomas Walsh, Vicar Apostolic of England’s Midland District (

one of the administrative regions of the English Catholic Church before the restoration of the hierarchy in 1850 - editor’s note), was a strong supporter of Pugin and “gave him almost a free hand in attempting to revive the old Gothic vestments of pre-Reformation days, besides encouraging him to build and restore churches in the Gothic style.” [1] This revival was not limited to England, however. On the Continent at this time, other figures were likewise involved in efforts to revive the use of Gothic vestments, including Dom Prosper Gueranger, abbot of monastery of Solesmes, and Canon Fanz Bock of the cathedral of Aix-la-Chapelle. [2]

Pugin’s efforts were quite successful and Gothic vestments were widely adopted by English clergy in these years. One notable public use of these vestments was at the opening of St. Mary’s College, Oscott in 1838 which was attended by several bishops and over 100 priests.

But not all members of the English clergy were enthusiastic about these trends. Some, like Bishop Augustine Baines of the Westland District, opposed Pugin’s vision for vestments, church ornamentation, the restoration of Gregorian Chant, and other parts of the ‘English Catholic Revival’. Baines forbade his clergy to wear Pugin’s vestments and complained to Rome about them. [3]

In 1839, Bishop Thomas Walsh of the London District received a letter from the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith which expressed displeasure with what he was permitting in his diocese. The letter also referred directly and dismissively to Pugin as “an architect converted from heresy” who was behind these innovations. Pugin corresponded about this with his friend and fellow convert Ambrose Phillipps De Lisle. De Lisle later wrote to another shared acquaintance and patron–John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury:

… that the College of Propaganda is to regulate even the minutest details of our ecclesiastical dress, is to assume for a foreign congregation a degree of power that has never yet been claimed by any Pope, no nor even by any General Council of the Church.

An uniformity of vestments or even of rites and Liturgies has never yet been enforced in any period of the Church [...] Italy has her Chasubles very different in many respects fm. those of France, of Germany, and of modern England [...] ; it is therefore idle to say that the restoration of the old English Chasuble hurts the uniformity of the Church, seeing that no such uniformity exists: it is equally idle to say that it infringes upon the rubricks ; when the rubricks were composed most assuredly the modern form of vestments existed not, and therefore if either offended against them, it wd. be the latter, not our glorious old English form. [...]

No, deeply do I deplore this lamentable business: its consequences if persisted in, will be most disastrous, the very idea of them fills me with horror and alarm. [4]

Despite the 1839 letter from Cardinal Franzoni to Bishop Walsh, and the initial despair of Pugin and De Lisle, no formal restrictions to the use of Gothic vestments were issued from Rome, and their use continued to spread throughout England, and in France, Belgium, and Germany.

English Revival: Continued Use

In June 1841, the new Cathedral of St. Chad in Birmingham–commissioned by Walsh and designed by Pugin–was opened in an extraordinarily grand ceremony attended by thirteen bishops from around the world (two from Scotland, one from the United States, and one from Australia) including Bishop Baines. [5] For this Mass, Bishop Nicholas Wiseman and the celebrating ministers wore a set of gold Gothic vestments which had been designed by Pugin. [6]

|

| Illustration of the original interior of the Cathedral of St. Chad in Birmingham. From Robert Kirkup Dent, “Old and New Birmingham: A History of the Town and Its People” (Birmingham: Houghton and Hammond, 1880), page 458. |

In the decades which followed, Wiseman would be appointed as the first Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster and become the driving force for trends within the newly re-established Catholic Church in England. He would continue to use Gothic vestments regularly. [7]

After the re-establishment of the Catholic Hierarchy and the First Provincial Synod of Westminster in 1852, now-Cardinal Wiseman traveled to Rome to submit the synodal decrees for Vatican approval. So widespread was the use of Gothic vestments at this time, it was rumored in the secular press that Rome intervened to edit the decrees in an attempt to regulate or ban them.

|

| 4. Dumfries and Galloway Standard and Advertiser, November 2, 1853, page 2. |

I have not been able to confirm if Roman authorities did actually intervene in this matter, but the rumor that they did so survived for decades. [8] In any case, the final approved Synodal decrees made only passing mention of vestments in extremely mild language: “That uniformity may prevail in these things, we must strive to shape our sacred vestments according to the pattern of the Roman Church.” [9]

The Roman Letter of 1863

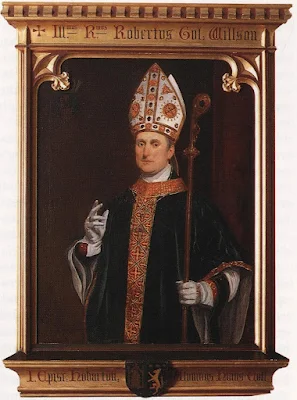

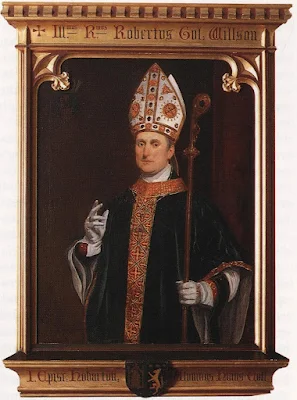

Interest in and use of Gothic vestments in these years continued to grow. After attending the 1841 opening of St. Chad’s Cathedral in Birmingham, Archbishop of Sydney John Polding became “quite taken” by Gothic Revival architecture and vestments and with his use and support they spread throughout Australia over the following decades. [10] The Bishop of Hobart in Tasmania, Robert Willson was a friend of Pugin and greatly admired his work. Willson ordered vestments by Pugin from England for himself to wear and as gifts to priests in his diocese, some of which survive to this day. [11]

|

| Robert Willson, bishop of Hobart, wearing Pugin-designed Gothic vestments. Painting by John Rogers Herbert, 1854. |

In June 1859, Bishop Johann Georg Müller of Münster, Germany (who had authorized the restoration of Gothic style for the preceding ten years) wrote a letter to Rome about the matter. In response, the papal master of ceremonies Johannes Corazza toured Germany and Switzerland with then-bishop and papal almoner Gustav Adolf zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst to view the vestments and discuss the matter with the priests and laity.

Afterwards, Corazza composed a lengthy report (which was privately transmitted but not published) in which he gave his private opinion that the Sacred Congregation of Rites should intervene and discontinue the use of Gothic vestments. [12] Corazza’s response is said to have been “radical and immoderate,” and met with considerable pushback from bishops across Germany, France, Belgium, and Switzerland. [13] Rome took no immediate action and the use of Gothic vestments continued and spread.

Four years later, the Vatican finally decided to intervene. On August 21, 1863, Cardinal Costantino Patrizi Naro of the Sacred Congregation of Rites wrote a circular letter to the bishops of England, France, Germany, and Belgium regarding a decision on Gothic vestments: “... as long as the present discipline lasts, nothing may be changed without consulting the Holy See[.]”

Patrizi also invited the bishops to respond and give their opinions as to why it would be beneficial to switch to Gothic vestments: “[a]s, however, the Congregation of Sacred Rites thinks that the reasons which led to the change in question may be of some weight, having referred the matter to his Holiness Pope Pius IX, it has been decided cordially to invite your lordship, in so far as these changes may have taken place in your diocese, to explain the reasons which led to them.” [14]

This concludes the first article in this series. The second article will explore the reception and effects of the 1863 letter, and the use of Gothic vestments between 1863 and 1925.

Notes:

[1] Denis Gwynn, The Second Spring, 1818-1852: a study of the Catholic revival in England (London: Burns & Oates, 1942), page 88.

[2] “Your correspondent, although what he refers to has happened many years ago, will never forget the impression he received when present one day at a High Mass celebrated by Dom Prosper Gueranger, Abbot of Solesmes, assisted by two of his monks, who were, like himself, arrayed in Gothic vestments. It was indeed priestly and decorous beyond expression. And Dom Gueranger has good claims to be considered a good judge in all liturgical matters.” See “Anent the Reform in Church Vestments” in The Ecclesiastical Review, March 1910, pp 349-350.

[3] Pamela Gilbert, This Restless Prelate: Bishop Peter Baines 1786-1832 (Herefordshire: Gracewing, 2006), pp 224-226

[4] Edmund Sheridan Purcell, Life and Letters of Ambrose Phillipps de Lisle, Vol II (London: Macmillan, 1900), pp 220-221.

[5] Bernard Ward, The sequel to Catholic emancipation: the story of the English Catholics continued down to the re-establishment of their hierarchy in 1850 (London: Longman, Greens & Co, 1914), pp 13-14.

[6] The vestments were originally donated by Shrewsbury to Bishop Thomas Walsh for the purpose of use at the opening of all new Catholic churches in this period of revival and restoration. Shrewsbury was a friend and patron of Walsh and Pugin and a strong supporter of the Catholic Gothic Revival.

[7] Several examples of Wiseman’s continued use of Gothic vestments are: the opening of St. Anne’s Church, Whitechapel, on September 8, 1855, in a ceremony attended by the Bishops of Southwark, Amiens, and Troyes along with a large number of English and French clergy (see Freeman’s Journal, December 22, 1855, page 5); the opening of St. John’s Church, Brentford (see Freeman’s Journal, August 29, 1857, page 4); and the solemn 1858 Christmas Mass at Westminster cathedral (see The Pilot, January 22, 1859, page 5).

[8] Rev. Edwin Ryan writing in 1935 said: “When the canon [of the Westminster Synod] was examined at Rome the word ‘Gothic’ was crossed out and ‘Roman’ substituted, because the Roman authorities thought that the English bishops wanted some vestment connected with the Gothic or the Mozarabic rite; but when a set of ‘Gothic’ vestments was shown to them they exclaimed: ‘Those are Roman vestments!’ ” (see “May we use ‘Gothic’ Vestments?” in The American Ecclesiastical Review, June 1934, page 576). Ryan’s account is not cited and has the classic flavor of an old wives’ tale, especially in light of the wording of the actual decree from the Synod. In any case, it is plausible enough that Wiseman did receive feedback on final phrasing regarding vestments given that some Vatican officials had long been aware and suspicious of Pugin, Walsh, and the general atmosphere of the English Catholic Revival.

[9] See The synods in English: being the text of the four synods of Westminster translated into English and arranged under headings (Stratford-on-Avon: St. Gregory’s Press, 1886), page 138. The original Latin text can be found in Acta et decreta primi concilii provincialis westmonasteriensis: habita Deo adjuvante mense Julio MDCCCLII (Paris: Migne, 1853), page 63.

[10] Polding was “quite taken with the sacred vestments which were designed and made under the supervision of Pugin for the Birmingham Cathedral’s consecration [...]Over the next few decades, this new form of vestment, referred to as Gothic, became common throughout Australia” (see “

Archbishop Polding's Gothic Vision” at the blog In Diebus Illis: Historical notes and images of 19th century Australian Catholicism). The second Archbishop of Sydney Roger Vaughan, following Polding, also regularly wore and was photographed wearing Gothic vestments.

[12] The letter from the Bishop of Munster was dated June 10th, 1859, and Corazza’s lengthy reply (apparently it was quite strident and ran to an astonishing 140 pages) was delivered in the same year. It took three more decades before it would be published in the Analecta Juris Pontificii (March & April, nos. 239 and 240) in 1888. I do not believe that this volume of the Analecta has been digitized, but a lengthy summary of Bishop Müller’s arguments in favor of the Gothic, and Corazza’s response, are provided by Rev. James Connelly in The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, Vol 10 (1889), pp 593-603 & 1035-1042.

[13] See “The Pattern of the Chasuble for the Mass,” The Ecclesiastical Review, December 1909, pp 684 & 686. It is even alleged in later recountings that Corazza’s letter displeased Pius IX and that he directed it be suppressed, but this seems unlikely given that the Sacred Congregation of Rites took action just four years later.

[14] Translation taken from Rev. John O’Connell, The Celebration of Mass: A Study of the Rubrics of the Roman Missal, Vol I (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company, 1941), pp 266-267.