An earlier litany at NLM invoked saints who had been driven into exile for the Faith. The largest single subcategory of exiles were the Byzantine iconophiles, bitterly persecuted by the iconoclasts. As many have pointed out (including me in an

earlier article at NLM), there have been three great periods of iconoclasm in the Church: the Byzantine period; the Protestant period; and the modernist period during and after Vatican II. In terms of the sheer quantity of religious art and architecture destroyed, the last of these three periods has been by far the worst

[i]—especially because the greatest of all holy “images,” namely the liturgy itself, was also violently defaced, and continues to subsist in many places in that condition. We are therefore all the more justified in calling on the intercession of those who gave their health, their limbs, their very lives, for the defense of holy icons.

A Litany of Saints Who Suffered for the Sake of Holy Images

(for private use)

Lord, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, have mercy on us.

Christ, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

God the Father, invisible and uncircumscribed,

have mercy on us.

God the Son, Image of the Father, made flesh for man,

have mercy on us.

God the Holy Ghost, sent under the form of a dove and tongues of flame,

have mercy on us.

Holy Trinity, one God,

have mercy on us.

Holy Mary,

pray for us.

Holy Mother of God,

pray for us.

Holy Virgin of virgins,

pray for us.

Ye forty-two holy monks of Ephesus, tortured under Constantine Copronymus,

pray for us.

St Lazarus, monk, tortured under Theophilus as a painter of sacred images,

St Tharasius, bishop, recipient of a letter from Pope Adrian I in defense of holy images,

St Euthymius of Sardis, bishop, exiled by Michael and martyred under Theophilus,

St Theophanes, monk, imprisoned, then exiled by Leo the Armenian for venerating images,

St Nicephorus, bishop, exiled to the island of Prokonesis for reverencing holy images,

St Paul of Constantinople, burnt to death under Constantine Copronymus,

St Nicetas of Apollonia, bishop, driven into exile,

St John Damascene, apologist of icons, whose cut-off hand was restored by the Mother of God,

St Macarius, who under the Emperor Leo ended his life in exile,

St Nicetas of Medikion, abbot, who suffered much under Leo the Armenian,

St Plato, monk, who strove dauntlessly against the heretical breakers of holy images,

St George of Antioch, bishop, who died in exile for the veneration of holy images,

St Anthusa, virgin, beaten with scourges for the veneration of holy images and exiled,

St Emilian, bishop, who suffered at the hands of the Emperor Leo and died in exile,

SS Julian, Marcian, and eight others, slain with the sword for venerating an image of the Saviour,

St George Limniota, whose hands were cut off and whose head was set on fire,

SS Hypatius and Andrew, who suffered flaying, burning, and the cutting of your throats,

St Theophilus, cruelly scourged and driven into exile by Leo the Isaurian,

St Andrew of Crete, monk, scourged by Constantine Copronymus who cut off thy foot,

St Theodore of Studium, zealous fighter for the Catholic veneration of holy images,

St Gregory Decapolites, who suffered much for the veneration of holy images,

SS Theodore & Theophanes, brothers, beaten and sent into exile twice for the honor due to icons,

pray for us.

Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world,

spare us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world,

graciously hear us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, who takest away the sins of the world,

have mercy on us.

V. There is no idol in Jacob, neither is there a simulacrum in Israel.

R. The Lord his God is with him, and the sound of the King’s victory is in him. (Num 23:21)

V. He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature:

R. For in him were all things created in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible. (Col 1:15–16)

Let us pray. Almighty everlasting God, who dost not forbid us to carve or paint likenesses of Thy saints, in order that whenever we look at them with our bodily eyes we may call to mind their holy lives and resolve to follow in their footsteps: may it please Thee to bless us by images made in memory and honor of Thine only begotten Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, and to grant that all who in their presence pay devout homage to Thine only-begotten Son may by His merits and primacy obtain Thy grace in this life and everlasting glory in the life to come, through Christ our Lord. Amen.

|

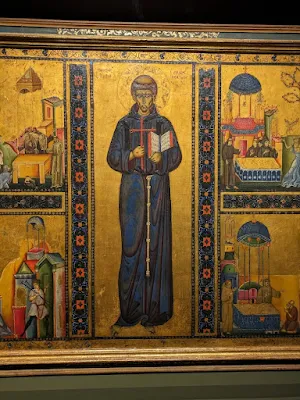

| St Andrew of Crete |

Sources in the Martyrology

At Ephesus, the passion of

forty-two holy monks, who were cruelly tortured under Constantine Copronymus in defense of the veneration of holy images, and consummated their martyrdom. (Jan 12)

At Constantinople,

St Lazarus, monk, who was tortured with dread torments by command of the Iconoclast Emperor Theophilus, because he painted sacred pictures. His hand was burnt with a hot iron, but he was healed by the power of God and repainted the holy pictures that had been destroyed. He ended his life in peace. (Feb 23)

At Constantinople,

St Tharasius, Bishop, famous for learmng and piety. A letter of Pope Adrian I to him, defending holy images, is extant. (Feb 25)

At Sardis,

St Euthymius, Bishop, who was sent into exile by the Iconoclast Emperor Michael because of his veneration of holy images. Later on during the reign of Theophilus he suffered martyrdom by being cruelly beaten with leather thongs. (Mar 11)

At Constantinople,

St Theophanes, who from being a very rich man became a poor monk. He was kept in prison for two years by the impious Leo the Armenian, for his veneration of holy images, and then exiled into Thrace, where, weighed down with miseries, he gave up the ghost. He was renowned for many miracles. (Mar 12)

At Constantinople, the translation of

St Nicephorus, Bishop of that city and Confessor. His body was brought to Constantinople from the island of Prokenesis, in the sea of Marmara, where he had died on June 5 in exile because of his reverence for holy images, and it was buried with honour by St Methodius, Bishop of Constantinople, in the church of the Holy Apostles in this the very day on which Nicephorus had been driven into exile. (Mar 13)

At Constantinople,

St Paul, Martyr, who was burnt with fire under Constantine Copronymus for his defense of the veneration of holy Images. (Mar 17)

At Apollonia,

St Nicetas, Bishop, who was driven into exile for the veneration of holy images, and there died. (Mar 20)

At Damascus, the festival of

St John Damascene, Priest, Confessor and Doctor of the Church, famous for his learning and holiness. By his writings and preaching he powerfully defended the veneration of holy images against Leo the Isaurian. When his right hand had been cut off by the Saracen caliph because of the calumnies of the emperor, he appealed to the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose images he had defended: forthwith he recovered his right hand, whole and well. (Mar 27)

At Constantinople,

St Macarius, Confessor, who under the Emperor Leo ended his life in exile for defending holy images. (Apr 1)

In the monastery of Medikion in Bithynia,

St Nicetas, Abbot, who suffered much under Leo the Armenian, for the veneration of holy images, and finally, as a confessor, died in peace near Constantinople. (Apr 3)

At Constantinople,

St Plato, monk, who strove with dauntless spirit for many years against the heretical breakers of holy images. (Apr 4)

At Antioch in Pisidia,

St George, Bishop, who died in exile for the veneration of holy images. (Apr 19)

In the island of Prokonesis in the Sea of Marmara,

St Nicephorus, Bishop of Constantinople; he was a most zealous fighter for the traditions of the fathers and fearlessly opposed Leo the Armenian, the iconoclast emperor, in regard to the veneration of sacred images. On this account he was exiled by him and, after a long martyrdom of fourteen years, departed to the Lord. (Jun 2)

At Constantinople, blessed

Anthusa, Virgin, who was beaten with scourges under Constantine Copronymus for the veneration of holy images, and being sent into exile, fell asleep in the Lord. (Jul 27)

At Cyzicus, on the Hellespont,

St Emilian, Bishop, who suffered much at the hands of the Emperor Leo on behalf of the veneration of holy images, and at last ended his life in exile. (Aug 8)

At Constantinople, the holy martyrs

Julian,

Marcian and

eight others, who after many torments were slain with the sword by command of the impious Emperor Leo because of an image of the Saviour which they had set up on a brazen gate. (Aug 9)

St George Limniota, a monk, who reproved the wicked Emperor Leo for breaking the holy images and burning the relics of the saints. At the latter's command his hands were cut off and his head set on fire, and he passed as a martyr to the Lord. (Aug 24)

At Constantinople, the holy martyrs

Hypatius (a bishop of Asia) and

Andrew (a Priest), whose throats were cut, under Leo the Isaurian, after their beards had been smeared with pitch and burnt, and their heads flayed because of their defence of the veneration of holy images. (Aug 29)

At Constantinople,

St Theophilus, monk, who was most cruelly scourged by Leo the Isaurian for defending the veneration of holy images, and driven into exile where he passed to the Lord. (Oct 2)

At Constantinople,

St Andrew of Crete, a monk, who was often scourged by Constantine Copronymus on account of his veneration for the holy images, and at length gave up the ghost after one of his feet had been cut off. (Oct 20)

At Beyrouth in Syria, the commemoration of the

Image of the Saviour, which when crucified by the Jews poured forth blood so plenteously that the churches of the East and West drew copiously from it. (Nov 9)

At Constantinople, St Theodore, Abbot of Studium, who fought zealously for the Catholic faith against the Iconoclasts and became famous in the Universal Church. (Nov 11)

At Constantinople,

St Gregory Decapolites, who suffered much for the veneration of holy images. (Nov 20)

At Constantinople, the holy confessors

Theodore and

Theophanes, brothers, who were brought up from childhood in the monastery of St Sabbas. They strove zealously against Leo the Armenian in defense of the veneration of holy images, and by his command were beaten with sticks and sent into exile. After his death they again bravely resisted the Emperor Theophilus, who continued the same impiety, and were again scourged and driven into exile. There Theodore died in prison; but Theophanes, when peace was at length restored to the Church, became Bishop of Nicaea, and, famous for his glorious witness for the faith, rested in the Lord. (Dec 27)

|

| St Theodore the Studite |

NOTE [i] Fr. Jean-François Thomas, S.J., noted: “France is an immense reliquary, both because of the number of saints who rest there and are venerated there, and because of the names of places. All who fought against this over the centuries were not mistaken: the Protestants, the first iconoclasts in France, destroyed reliquaries and relics, and burned pilgrimage shrines; then the French Revolution completed the sacrilege by attacking relics and confiscating the precious metals and gems of the reliquaries for its war effort; not to mention—which is really the last straw!—that a portion of the clergy itself, in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, decided that all these superstitions no longer made sense and, having become effectively Protestant, removed reliquaries from churches or sold them to the highest bidder. A cultural heritage curator told me thirty years ago that, in the region for which he was then responsible, the post-Vatican II destructions had without doubt been more significant than those that took place during the French Revolution itself” (

Are Canonizations Infallible? [Arouca Press, 2021], 7).

.jpeg)