One of the recurring themes of the pontificate of Benedict XVI was the vital nature of Sunday. At the 2005 Eucharistic Congress, at the 2005 World Youth Day, and in a 2007 sermon in Vienna, the Pope repeated an arresting line from the acts of the martyrs. In A.D. 304, forty nine Christians were apprehended for assembling on Sunday, in violation of imperial law. When the Proconsul asked them “why on earth they had disobeyed the Emperor’s severe orders,” one of them, a man named Emeritus, replied: Sine dominico non possumus. [1] Emeritus’ response has been justifiably translated “Without Sunday we cannot live,” but its literal meaning is even more astonishing: “Without Sunday, we cannot exist.”

Friday, April 28, 2023

Undoing the Dismal: Liberating Sunday’s Soul

Michael P. FoleySandor Bihari, “Sunday Afternoon,” 1893

Sustaining Life

Why make such a fuss over a day of the week? Pope Benedict was reflecting on this question years before his elevation to the throne of Peter. For the early persecuted Christians, he wrote in 1996, it was not “a case of choosing between one law and another, but of choosing between the meaning that sustains life and a meaningless life.” [2] We may get a sense of this meaning by applying one of the things that YHWH said about the Hebrew Sabbath to the Christian Sunday: “If thou turn away… from doing thy own will in My holy day, and call the Sabbath delightful, and the holy of the Lord glorious, and glorify Him… Then shalt thou be delighted in the Lord, and I will lift thee up above the high places of the earth, and will feed thee with the inheritance of Jacob thy father.” (Is. 58.13,14).

Note the essential elements of God’s promise: The Lord has established a holy day, and man’s proper response is to: 1) turn away from his own will and conform it to the will of God, 2) delight in that holy day, and 3) glorify God. If these conditions are fulfilled, God will be someone we truly love rather than merely obey, and we will be lifted up above our earthly drudgery and fed with a heavenly inheritance. A proper observance of the Lord’s holy day, in other words, is a life-transforming experience that gives new meaning to our existence. No wonder that as early as the second century, St. Ignatius of Antioch was defining Christians as those “who live in accordance with Sunday.” [3]

Amalia Lindegren, “Sunday Evening in a Farmhouse in Dalecarlia”, 1860

The Christian Sabbath?

As our use of Isaiah would suggest, it is tempting to think of Sunday as the “Christian Sabbath.” One must be careful here, however. While it is true that the duties of the Third Commandment regarding the Sabbath (Saturday) have been transferred to Sunday, Sunday springs not from the Old Covenant but from the Resurrection. The Day of the Resurrection falls on the first day of the week, in which God created light, and thus it marks a new beginning and a new creation. Every Sunday is a little Easter, or better yet, every Easter is a big Sunday. [4] The risen Christ’s sanctification of Sunday was a reality the Church appropriated slowly but surely: in the Acts of the Apostles, the first Christians observed the Jewish Sabbath along with their own services the next day, (18.4; 20.7), but by the time the Book of the Apocalypse was written, St. John could speak of “the Lord’s Day” (1.10) with the expectation that his readers would know exactly what day he was talking about. [5]

Freedom from Servility

Sunday also became a day of rest. In 321 the Emperor Constantine, wishing to extend the same honor to Sunday traditionally accorded to pagan feasts, forbade courts to be in session and most kinds of manual labor. Interestingly, canon law lagged behind civic law in regulating Sunday as a work-free day, though Church officials eventually came to see Sunday, like the Sabbath it replaced, as a way of conforming ourselves to God’s will by refraining from the busywork to which we, laden with cares, become addicted.

Fundamental to this rest is the distinction between servile labor (the kind of work a servant or hired hand does) and liberal activity, that which liberates the soul or is befitting a free man—reading and writing, arts and entertainment, sports and games, hobbies, etc. Hence the 1917 Code of Canon Law forbids on Sundays and holy days of obligation all “servile work, judicial proceedings and, unless legitimate custom or special indults permit them, public trafficking, public markets, and all other public buying and selling” (1248).

The prohibition of servile work had a tremendous impact on Western life, for it meant, among other things, that once a week a slave was his master’s equal. As early as the fourth century, many masters would even release their slaves from work on Saturday so that they could better prepare for the Lord’s Day, a custom that foreshadows our modern weekend. [6] And because a slave’s labor was his own on Sunday, he could eventually earn enough money to buy his freedom. In 1724, King Louis XV of France issued the Code Noir, a set of laws protecting slaves and free persons of color in Louisiana. As a result, many slaves and free blacks could gather every week at the old Congo Square in New Orleans, where they would dance and sing to the beat of an African drum, an instrument banned in most other parts of the Protestant-dominated American South. From this freedom to foster and develop culture came the eventual formation of that uniquely American music: jazz. The joy and genius that springs from Sunday is a perfect illustration of Aristotle’s paradoxical observation that all action begins in contemplation.

E.W. Kemble, Congo Square, 1886

Savoring the Useless

Aristotle privileges contemplation because it is the activity of what is highest in us, our capacity to transcend space, time, and matter and to revel in wonder and discovery. As Joseph Pieper argues in his well-known study Leisure: The Basis of Culture, any attempt to deny this “divine spark” ultimately dehumanizes us, reducing us to mere economic or social units. Servile labor is obviously a good thing, but its prohibition on Sunday reminds us that it is not the highest thing. The servile arts are around because they are useful, but that means we are using them to get to some other, greater good we want more.

A good, on the other hand, that we want for its own sake is something we enjoy: it is choice worthy regardless of its utilitarian value. When I read my favorite author, it is not because he can help me with my job or my relationships or my car problems but because his work brings me delight; it is a joy to read, even if there are no practical applications to be derived from it. All of our useful skills and pursuits are there to serve our enjoyment of what is, strictly speaking, useless.

Sunday rest is therefore an essential weekly reminder of the true hierarchy of goods, an admonition to make sure we are not mistaking the means for the end. In our consumerist society, this is no easy task. For the last three hundred years the West has placed an exorbitant emphasis on productivity and practicality, portraying the useful as good and the useless as bad.

But the Catholic intellectual tradition, lifting a page or two from classical philosophy, sees through the falseness of this view. It affirms that while the useful is indeed good, it is not as good as a certain category of the useless. Man is meant for something far higher than being a mere consumer or producer, as the two giants of capitalism and communism would both have us believe: man is meant to contemplate the face of God and be happy. As the new Catechism succinctly puts it, the Sabbath “is a day of protest against the servitude of work and the worship of money” (2172). [7] While six days of the week enable us to pay the bills and maybe ensure a decent retirement, Sunday enables us to anticipate the ultimate freedom of enjoying the bliss of the Beatific Vision in eternity.

Sunday, therefore, is a gift that God gives all of us every week to add dignity to our lives and to elevate our natures. And it is our privilege to accept this gift. In the words of Cardinal Faulhaber, “Give the soul its Sunday, and give Sunday its soul.” [8]

Lands Without a Sunday

In the modern era the dramatic increase of white-collar professions and new fields of knowledge sometimes makes it difficult to identify what activities are and are not suitable for Sunday. As Cardinal Newman noted over a century ago, there “are bodily exercises which are liberal, and mental exercises which are not so.” [9] If I practice woodworking as a hobby, I am engaging in the same manual labor as a professional carpenter but in a liberating, non-servile way. Conversely, if I am studying theology (the most liberal of all the arts) in order to meet a publishing deadline, I am taking the liberating luster off of my activity; “for Theology thus exercised,” Newman writes, “is not simple knowledge,” but “an art or a business making use of Theology.” [10] Whatever we do on Sunday, be it with the hand or the mind, we must be careful that it not be “cut down to the strict exigencies” [11] of utilitarian ends but wrought purely for the sake of relaxation and enjoyment.

Sunday’s decline in modern life is not due to an increasingly complex workforce, however. As Pieper notes, the modern doctrine of “total work” has left little room for a genuine celebration of Sunday. This was true even fifty years ago, when Christians of all stripes adhered to the principle of Sunday rest and when civic laws still protected Sunday from consumerist encroachment. [12]

Maria Trapp, inspiration behind the Sound of Music, gives a concrete example of this in her excellent essay, “The Land Without a Sunday.” [13] The title is ostensibly a description of life in the Soviet Union, which ruthlessly suppressed the Lord’s Day, but as becomes clear from reading on, it also applies to contemporary America. [14] The Trapp family, which started preparing for Sunday the day before by refraining from work and reading the texts of the Mass together and then spending the Lord’s Day in joyous leisure, was shocked by what they saw when they came to the U.S. in 1938: Saturday nights spent in revelry and Sunday mornings spent hung over; farmers doing work on the Lord’s Day as on any other; and the bells of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City silent because “it would be too much noise”—in New York City, mind you. [15] “When we lived in a suburb of Philadelphia,” Maria Trapp writes, “we found that the rich man’s Sunday delight seemed to consist of putting on his oldest torn pants and cutting his front lawn, or washing his car with a hose.” [16]

Mrs. Trapp also discovered another cause behind the demise of the traditional Sunday: Calvinism. Her children were stunned when a woman told them how much she “hated Sundays.” The reason, they learned, is that she was brought up in a Puritan household where her mother would lock up all the toys on Saturday night. On Sunday morning, after a long sermon in church, the children were forbidden to play any games, listen to any music, or have any kind of fun. The lady went on to say that she vowed permanent rebellion against this upbringing and would never force her children to go to church.[17]

The Trapp’s friend was not describing an isolated incident. After the Reformation, sports and popular amusements (to say nothing of open pubs) were forbidden in several countries.[18] Sunday was now defined as a time for instruction, not enjoyment.

Calvin preaching, 19th century representation

And alas, the Catholic Church has not fared well in counteracting these tendencies. The post-conciliar allowance of Vigil Masses, some as early as 2:30 p.m. on a Saturday afternoon,[19] has compromised Sunday’s integrity, while for the past several decades the Magisterium has omitted virtually all references to servile work in discussions on the Lord’s Day: the term has been dropped from the 1983 Code of Canon Low and from the new Catechism. [20] My guess is that there was a concern over confusing servile work and manual labor, yet as we saw with Cardinal Newman’s remarks, the concept of servile work actually clarifies rather than conflates the difference between working with one’s hands and working for a mercenary or utilitarian end.

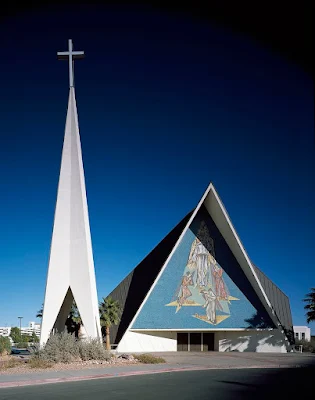

Guardian Angel Catholic Cathedral in Los Vegas, Nevada, has a 2:30 p.m. Saturday Vigil Mass

Whatever the motive, the absence of the servile/liberal distinction and the concrete parameters that flow from it make it easy for the individual to bend Sunday to his will rather than vice versa and contribute to the deterioration of a more socially-shared observance. The new Catechism, for example, speaks eloquently of Sunday’s purpose and of the fact that “sanctifying Sundays and holy days requires a common effort” (2187), yet working in common is more difficult when there is no concrete, common understanding of what should and should not be done. [21]

Take Back the Day

Instead of dwelling on our current “dismal” situation (a word that, incidentally, means “bad day”), I would like to offer five practical suggestions for giving Sunday back its soul.

1. Resist commercial temptations. An attentive casuist might note that since the 1917 Code of Canon Law prohibits "public buying and selling" on Sunday, it is acceptable to shop online in the privacy of one's own boudoir on the Lord's Day. True, but the more we can resist the temptations to earn or spend money on this day, the better. St. Louis Martin, the father of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, refused to open his jewelry shop on Sunday even though his confessor permitted it, nor did he buy anything on the Lord’s Day. One Sunday, when he saw an item he really needed, he asked the vendor to hold it for him until the following day. [22]

2. Agape. The agape meal was the primitive Church’s banquet after the conclusion of the Eucharistic liturgy. The family Sunday dinner, celebrated with extra festivity, is one adaptation of this Apostolic custom (and perhaps in the spirit of relieving the downtrodden, it could be spearheaded by Dad and the kids instead of Mom). Similarly commendable is the coffee-and-donuts hour which many churches offer after Mass. These gatherings foster Catholic fellowship as well as the leisurely quality of the day by discouraging the race-out-of-the-parking-lot mentality so many American Catholics have the moment their Sunday obligation has been fulfilled.

3. More than Mass. Another way to avoid reducing Sunday to one begrudgingly-conceded hour at church is to punctuate it with other forms of prayer. In Europe many churches held Solemn Vespers on Sunday evening, so much so that Sunday dinner was often called the “vesper meal.” Exposition and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, the family rosary, and the recitation of Lauds and Vespers are other ways of sanctifying the day to God.

4. Attend the Latin Mass. A friend of mine found himself attending the Latin Mass several years after his conversion. It was at that point, he told me, that the concept of a “Sunday obligation” no longer made sense to him. He could not see Sunday Mass as an obligation any more: it was instead the highpoint of his week, the one thing he really looked forward to. There is something about the traditional Latin Mass, especially the High Mass, that slips the surly bonds of necessity or compulsion, of utilitarianism or functionality. It is there to be enjoyed, to give us an experience of Heaven. Pope Benedict spoke of how the “Sunday precept is not… an externally imposed duty, a burden on our shoulders” but “a joy.” [23] For more than a few Catholics, this joy comes easy to see thanks to the Latin Mass. And my friend, incidentally, is now a priest for the Institute of Christ the King.

5. Fill your day with merriment. Plan games for your children and find fun ways to bring the sacred meaning of the day to their level. When my children were young, we had “sacred theatre,” which is something like a puppet show of the Epistle and Gospel readings performed with homemade cardboard cutouts. Another personal recommendation is reading Pieper’s Leisure: the Basis of Culture. [24] Early in our marriage, my wife and I would read chapters of it to each other after we came home from Mass and brunch with friends. It is one of my happiest memories of our salad days. And how fitting to learn the theory of leisure while practicing it.

Conclusion

The nineteenth-century poet Ahad Ha’am is said to have made the famous observation, “As much as the Jews kept the Sabbath, the Sabbath kept the Jews.” No doubt something similar can be said of Catholics and the Lord’s Day. Nowadays Sunday is honored, even by practicing Catholics, more in the breach than in the observance, and the only ones that seem to have responded to the Pope’s admonitions are a splinter-group of Seventh Day Adventists worried that this ominously signals a return to the Holy Roman Empire.[25] While there may not be easy answers for the proper way to observe the Lord’s Day in the contemporary age, one thing is clear: The first step to any recovery, not just of the liturgical year but of the Catholic life of faith, is the reconquista of Sunday.

An earlier version of this article appeared as “Undoing the Dismal: Liberating Sunday’s Soul,” The Latin Mass magazine 18:2 (Spring 2009), pp. 32-35. Many thanks to the editors of TLM for allowing its publication here.

Notes

[1] Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI, 24th National Eucharistic Congress, Bari, Italy, 29 May 2005.

[2] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, A New Song for the Lord: Faith in Christ and Liturgy Today, trans. Martha M. Matesich (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 1996), 60.

[3] juxta dominicam viventes. Ep. ad Magnesios, 9, 1-2. Cited in the Bari Homily (see fn. 1).

[4] Cf. John Paul II, Dies Domini 2.19.

[5] Although the supremacy of Sunday to Christian life was well-established by the second century, the double observance of the Sabbath and the Lord’s Day persisted in some parts of the Church into the fourth century. To this day the Greek Church considers Saturday as well as Sunday exempt from all laws of fasting and abstinence.

[6] Francis X. Weiser, S.J., Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs: The Year of the Lord in Liturgy and Folklore (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1958), 9.

[7] Judging by the context, this applies to the Lord’s Day as well.

[8] Quoted by Pope Benedict XVI in his homily delivered during Mass at St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna, 9 September 2007.

[9] John Henry Cardinal Newman, The Idea of a University (London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1907), 107.

[10] Ibid., 109.

[11] Ibid.

[12] The one notable exception are the Seventh Day Adventists.

[13] See Maria Augusta Trapp, Around the Year with the Trapp Family (New York: Pantheon, 1955), 186-202

[14] It is ironic that two such antithetical systems of human organization should breed such similar vices.

[15] Trapp, 198.

[16] Ibid., 199.

[17] Ibid., 200.

[18] Weiser, 10.

[19] Saturday vigil Masses are not per se bad (in early Christian Rome they occurred every Ember Saturday); it is the way they are used today that is problematic.

[20] The new Code of Canon Law states that the faithful “are to abstain from those works and affairs which hinder the worship to be rendered to God, the joy proper to the Lord’s Day, or the suitable relaxation of mind and body” (1247). An excellent formulation, but why not retain the notions of servility and liberality?

[21] The new Catechism has perhaps also conceded too much to our consumerist economy by not speaking with sufficient verve against the market’s increasing tendency to treat Sunday as any other day.

[22] Celine Martin, The Father of the Little Flower, trans. Michael Collins (Tan Books, 2005), 11-12.

[23] The Bari Homily (fn 1).

[24] Just about anything written by Pieper makes excellent Sunday reading. Another fitting choice would be Pope John Paul II’s 1998 Apostolic Letter Dies Domini (the Lord’s Day).

[25] For a good laugh, see Gerald Flurry, “The Pope Trumpets Sunday,” The Trumpet (November 2005).

%20Bihari,%20Sandor.jpg)