This is the sixth installment of a series on the thirteen papal namesakes of our new Holy Father Leo XIV; click these links to read part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, and part 5. Let’s pretend that the long delay since the last installment was deliberately made so that this could be published on the anniversary of Leo XII’s election.

On this day in the year 1823, Cardinal Annibale della Genga was elected Pope, and took the name Leo XII in honor of the previous Leo, who had somehow found the time during his very brief papacy to ennoble the della Genga family. His predecessor, Pius VII, was then the fourth longest reigning pope of all time, at over 23 years and 5 months. (He has since been surpassed by three more, Bl. Pius IX, Leo XIII, and St John Paul II, and dropped back to seventh). Cardinal della Genga had long been in poor health, and was chosen to be a transitional pope; during the conclave, he even said to the cardinals, “You are electing a dead man.” But as happens so often with transitional popes, he recovered his health enough to live longer than expected, dying nearly 5½ years later on February 10, 1829.

.jpg) |

| A portrait of Pope Leo XII, 1828, by the Belgian artist Charles Picqué (1799-1869). |

He was born in 1760, the sixth of ten children, and embarked on an ecclesiastical career from a very early age, enrolling in the diplomatic academy in Rome when he was only 18; he was ordained a priest by special dispensation at 22. In 1793, he was consecrated bishop and sent as a nuncio first to Switzerland, then to Cologne. In the wake of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, all of Europe was in a state of constant upheaval; relations between Church and state were very difficult, not least because of the gigantic theft of ecclesiastical property taking place everywhere, and the suppression of countless Catholic institutions of every sort. Bishop della Genga served the Church well in these turbulent times, but was disliked by Napoleon; he therefore returned to Italy, and went into a quiet early retirement at an abbey near his native place, a rural area within the Papal State, about 140 miles north north-east of Rome.

|

| A portrait of Ercole Cardinal Consalvi, 1819, by the English painter Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830). |

With the sudden fall of Napoleon in 1814, and the restoration of the French monarchy, it seemed that his career might be revived, as he was chosen to go to France and deliver the pope’s message of congratulations to Kind Louis XVIII, However, this did not please Pius VII’s Secretary of State, Ercole Cardinal Consalvi, and he was swiftly sent back to his retirement. Pius VII granted him the cardinalate, with his title at Santa Maria in Trastevere, and appointed him bishop of Senigallia, a town on the Adriatic Coast close to the della Genga’s land (and the birthplace of Bl. Pius IX), but due to his poor health, he never took possession of the diocese, and resigned it after about six months. Two years later, his health had improved enough that he was made Vicar of Rome, and archpriest of St Mary Major; he received the latter title on February 10, 1818, the same date upon which he would die 11 years later. He also served as prefect of various congregations.

When Pius VII died in 1823, attitudes within the Church were sharply divided. One party, known as the “moderati” in Italian, believed in finding and maintaining accommodations between the Church and the new secularized states of post-Napoleonic Europe, which had been very much the policy of Pius VII and Cardinal Consalvi. The other, known as the “zelanti – the zealous”, sought to retrench upon the old ways of the pre-revolutionary world. (Like all such characterizations, this is probably an oversimplification; this is a part of history in which I claim no expertise.)

Leo XII was elected as a representative of the zelanti, after the Austrian emperor had interposed a veto on their preferred candidate, a cardinal named Severoli. He himself predicted almost at once to the candidate of the moderati, the one much preferred by the major European powers, Cardinal Castiglioni, that he would be elected next. This did indeed happen, and Castiglioni’s choice of papal name, Pius VIII, was a deliberate sign of return to the policies and ideas of the moderati.

|

| Pius VIII being carried into St Peter’s Basilica on the sedes gestatoria, 1829, by the French artist Horace Vernet (1789-1863). |

Ercole Consalvi was immediately replaced as secretary of state by Cardinal Giulio Maria della Somaglia, who was then almost 80 (16 years older than Leo himself), a choice that was perhaps emblematic of this desire of the zelanti to return to an old world that had passed away. However, in the management of the Church’s affairs, Leo did in fact quite prove successful, and nothing like the fanatic he is often misrepresented as. He had the wisdom to take Consalvi into his counsels, and the latter had the wisdom to let bygones be bygones and offer the pope whatever advice he could. In 1800, amid the universal chaos wrought by Napoleon, no jubilee was held in Rome, and by 1825, many people, and indeed, many Catholics saw the event as just another relic of a dead past. Leo XII proclaimed it anyway, and it proved a huge success, drawing half-a-million pilgrims. The pope also rallied opposition to renascent persecution of Catholicism in the Netherlands, and encouraged the movement towards Catholic emancipation in Great Britain.

He is, however, nowadays remembered unfavorably in Italy for his governance of the Papal State, which was reactionary and repressive. A dear friend of mine, a priest who is very well versed in the modern history of the Church, once described the Papal State in its latter days as “the Afghanistan of 19th century Europe.”

The Catholic Encyclopedia’s article on Leo XII sums the matter up very nicely: “There is something pathetic in the contrast between the intelligence and masterly energy displayed by him as ruler of the Church and the inefficiency of his policy as ruler of the Papal States. In face of the new social and political order, he undertook the defense of ancient custom and accepted institutions; he had little insight into the hopes and visions of those who were then pioneers of the greater liberty that had become inevitable.”

But writing once again as one with no expertise in this area of history, I make bold to add the following. This article was written in 1910, at a point when the social upheaval and violence let loose by the French revolution and the Napoleonic wars, and the “inevitable greater liberty” of European society, had not yet reached its crescendo in the unrelenting massacres of the two world wars. The Church itself is now still recovering from its own dizzy and wholly misplaced optimism about the modern world and its place within it. So perhaps the day will come when the forebodings of Leo XII and the other zelanti about what the new order of things would do to society will seem wiser than they have hitherto.

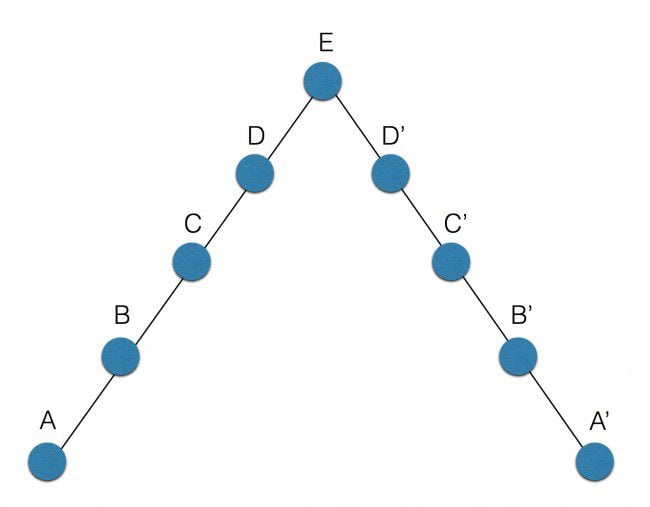

As noted above, Leo XII’s health had already long been bad at the time of his election, and he is supposed to have received extreme unction 17 times during his papacy. Towards the end of his first year as Pope, he came very close to dying, and was saved only when his close friend, the Passionist St Vincent Strambi, bishop of Macerata and Tolentino, offered his own life to God in exchange for the pope’s recovery. He finally passed away a few days after being taken severely ill in February of 1829. He is buried in the floor of St Peter’s basilica, before the altar which holds the relics of his first papal namesake; those of Saints Leo II, III and IV rest in the altar immediately to the left.

|

| The altar of Pope St Leo I in St Peter’s basilica. |

.jpg)

_-_facciata_1_2022-08-08.jpg)