The Vatican “Ban” of 1925

The use of Gothic vestments continued to spread in England and elsewhere. For example: by 1925, it was reported that every single Catholic church and chapel except one (the Oratory of St. Philip Neri) in the Diocese of Birmingham used Gothic vestments. [38]

That year was a momentous one for the story of Gothic vestments. Pope Pius XI had proclaimed 1925 as a Holy Year, and Rome was chosen as the host city for an International Exhibition of Modern Christian Art. During the exhibition, “newly-made vestments, according to the Borromeon proportions, were shown in a special audience with Pius XI, who approved their use and blessed them.” [39]

Afterwards, there seems to have been a desire by some in Rome to walk back any idea of increased Gothic permissions. On December 9, 1925, the Sacred Congregation of Rites responded to a question regarding vestments. The rescript was exceedingly brief, did not formulate any new regulations or details, and simply referred the question back to the well-known letter of 1863, which was appended to the response:

[Question]: In the making and use of vestments for the sacrifice of the Mass and sacred functions, is it permissible to depart from the accepted usage of the Church and introduce another style and shape, even an old one?

[Response]: It is not permitted, without consulting the Holy See, in accordance with the Decree or circular letter of the S.R.C., given to Ordinaries on August 21, 1863. [40]

This was the very first time that the text of the 1863 letter had been published in any official collection of decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites. It is likely for this reason that the 1925 reply was commonly viewed as a ‘new’ or ‘updated’ Roman intervention on Gothic vestments, despite the fact that the reply merely pointed back to the original letter.

|

| The Ecclesiastical Review, Dec, 1925, p. 626 |

The 1925 reply quickly raised questions around the world. It was reported in some quarters as an attempt to stop the widespread adoption of Gothic vestments. The editors of the Ecclesiastical Review answered several questions about it, discussed the original 1863 letter, and again did not interpret the decision to mean that ongoing use of Gothic vestments (or even the manufacture of new ones) was forbidden:

“Hence, while the use of the so-called Roman chasuble, in which the shoulder parts slightly overlap, is recognized as the prevailing approved custom, many churches in England, Germany, America, and even in Rome, adopt what is designated as the Gothic style to distinguish it from the purely Roman. It is certainly the more graceful of the two, and hence is commonly adopted in ecclesiastical art.” [41]

“The use of the Gothic chasuble in the modified form adopted by St. Charles and proposed by Bishop Gavanti, the Roman master of Pontifical ceremonies, is not forbidden. [...] The traditional right, which is not merely a privilege, of using Gothic vestments as described, was not abrogated by Pius IX or the S. Congregation, but continues wherever it has been regularly or accidentally adopted before that time.” [42]

As news of this reply from Rome spread in English-speaking lands, it produced a decent amount of confusion, and in some cases seems to have been met with barely a shrug. [43] Tongue-in-cheek commentary was offered in diocesan newspapers about the “battle of vestments” and the absurdity of attempting to define how ‘amply cut’ a vestment could be before it became forbidden.

|

| The Catholic Transcript, April 15, 1926. p. 4 |

Gothic Vestments after the ‘ban’ of 1925

Given this reception and interpretation of the 1925 rescript, it will not be surprising that Gothic vestments continued to be used and continued to spread in the years which followed. In the decade following the 1925 document, they were discussed as normal and licit things by diocesan newspapers and the US Bishops’ news service; they were manufactured and advertised by church goods retailers, they were used in the presence of bishops and by bishops themselves; they were even used by papal legates and by the pope himself!

|

| Gothic Chasuble commissioned in 1929 by Cardinal Francis Bourne. From Dom E.A. Roulin, Vestments and Vesture: A Manual of Liturgical Art (London: Sands & Co, 1933), page 94. |

- In 1926, Gothic vestments were used at the Solemn Midnight Mass at the Franciscan Monastery of the Holy Land in Washington, DC. [44]

- In 1927, the US Bishops’ news service praised Sacred Heart church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for fostering a liturgical revival and specifically commented upon the exclusive use of Gothic vestments. [45]

- In 1929, a special set of Gothic vestments was worn on the feast of St. Ignatius and Golden Jubilee of Rev. William Cunningham, SJ at the Church of the Gesù in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. [46]

- In 1929, Cardinal Francis Bourne commissioned Gothic vestments for Westminster Cathedral during the celebration of the centenary of Catholic Emancipation. [47]

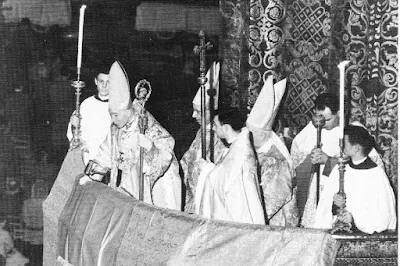

On March 19, 1930, Pope Pius XI used Gothic vestments during mass at St. Peter’s, and allowed himself to be photographed while doing so. [48] Gothic vestments were widely used throughout Rome during these years, including by cardinals in the catacombs, at the Basilica of St. Sebastian, and in celebrations organized by the Pontifical Academy of Martyrs and presided over by the papal master of ceremonies. [49]

|

| Pope Pius XI celebrating Mass in a Gothic chasuble made for him by the Poor Clares of Mazamet, France. Source: Raymund James, “The Origin and Development of Roman Liturgical Vestments” (Exeter: Catholic Records Press, 1934), page 2. |

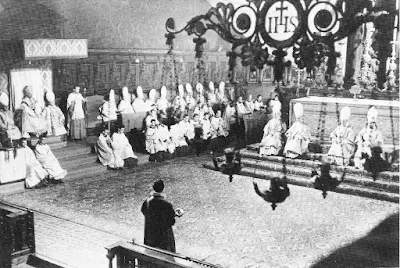

In 1934 the Catholic Church in Australia held a National Eucharistic Congress in Melbourne, celebrating the centenary of the church in that country and featuring “unprecedented” spectacular ceremonies and vast numbers of clergy and laity. On November 30, following the opening ceremonies for the congress, pontifical high mass was celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral by papal legate Cardinal Joseph MacRory in the presence of 60 bishops and 450 priests from around Australia. The cardinal and celebrating ministers wore Gothic vestments. [50]

|

| The Telegraph (Brisbane), Nov. 30, 1934, p. 7 |

The following day Archbishop Filippo Bernardini, papal nuncio to Australia, celebrated another pontifical high mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral for a crowd of more than 7,500 people, wearing Gothic vestments, which were frequently used throughout the Eucharistic Congress. [51]

Full approval of Gothic Vestments

In the years which followed, various members of the hierarchy of Australia continued to use Gothic vestments in high-profile settings, as in 1937, when Archbishop of Adelaide Andrew Killian used them during the consecration of Francis Henschke as Bishop of Wagga Wagga. [52]

They continued to receive official approval and use around the world during these years, for example, being authorized for the Archdiocese of Malines by Cardinal Jozef-Ernest van Roey in 1938, and by the Second Diocesan Synod of Quebec in 1940. [53]

Gothic vestments even reached the literal ends of the Earth during this period. During the US Navy’s Antarctic Expedition, on January 26, 1947, the first ever Catholic Mass offered in Antarctica was celebrated in extremely rustic conditions in the mess hall of camp ‘Little America IV’ on the Ross Ice Shelf. Rev. William Menster, chaplain of the flagship USS Mount Olympus, used green Gothic vestments. [54]

|

| At left, Rev. William Menster; at right, the USS Mount Olympus (AGC-8) in Antartica, 1947. (Sources: left and right.) |

Finally, on August 20, 1957, the Sacred Congregation of Rites issued a decree which gave bishops the right to permit the use of Gothic vestments in their own dioceses. From this point onward their use, which had been regular throughout the world by priests and bishops alike since 1925, only further increased.

|

| NCWC News Service, Aug. 31, 1957, wire copy p. 8 |

Conclusions

This concludes our survey of the use of Gothic vestments between 1841 and 1957. It is a story far more complex and fascinating than that depicted by conventional narratives. What can we make of all this? I think there are several key points which are worthy of summary and further discussion.

First, it is abundantly clear that the ‘revival’ of Gothic vestments in the modern period was much more widespread throughout Europe–particularly in England, France, and German-speaking lands–much earlier than commonly thought. By 1849 it was authorized by multiple bishops (in some cases on a diocesan-wide basis) across the continent.

Second, it is also clear that from the very early days of the Gothic revival, there were some officials in Rome who were skeptical and disapproving of the use of these vestments. The number of those who disliked the Gothic, as well as their roles and the intensity of their opposition, varied over the years. On multiple occasions, the popes themselves directly gave approval for and/or approving remarks about Gothic vestments. But in general, there was consistently more opposition than support from various members of the curia.

Despite this, it is also evident that Rome did not ever unequivocally condemn or actually attempt to stamp out the practice, and that there was widespread toleration of Gothic vestments, which evolved into permission to the local bishops. [55] There were no formal restrictions against Gothic vestments until the circular letter of 1863, and even then it was not viewed by chanceries and clerical journals around the world as a strict ‘ban’. The text of the letter was not published for more than 60 years afterwards and not a single different or clarifying statement was ever issued by Vatican officials.

It’s obvious that there was a persistent lack of clarity on what Rome permitted, tolerated, or forbade, as is evident from the number of times the question was raised in clerical journals and Catholic periodicals). There was also a widespread interpretation that Gothic vestments could continue to be used with the permission of the bishop. Because of this, the situation varied from diocese to diocese and region to region. In some cities or dioceses, the use of Gothic vestments was fully approved; in others, it was forbidden or limited.

All of this demonstrates how difficult it would be to claim that there was a clear message from Rome or to assign the label of disobedience to those many priests, bishops, and laity who produced, purchased, and used Gothic vestments for decades even after the 1863 letter. They were discussed approvingly in diocesan newspapers, permitted and used by the bishops and cardinals of the region, and routinely sanctioned by canonical and clerical journals. If the use of these vestments was in fact disobedient or forbidden during these decades, could the common priest or member of the laity have been expected to discover that fact with any certainty? [56]

Even after the Vatican rescript of 1925–which merely pointed back to the 1863 letter, and again, was not interpreted as a ban–the use of Gothic vestments did not slow or diminish. Just 5 years after the rescript, the pope himself was photographed in Gothic vestments. Within less than a decade, multiple papal nuncios and legates were regularly using them in the most high-profile and public ceremonies possible.

|

| Photograph of the Gothic vestments blessed by Pope Pius XI in 1925. Source: Dom E.A. Roulin, Vestments and Vesture: A Manual of Liturgical Art (London: Sands & Co, 1933), page 82. |

Because the use of Gothic vestments was so widespread before 1900 (and was desired and encouraged by so many different priests and bishops in so many different countries for so many years) it seems clear that it would have been essentially impossible to avoid the trend even without the advent of the modern Liturgical Movement in the 1920s.

If Rome truly viewed the ongoing use of Gothic vestments as a clear abuse or explicitly forbidden, it must be said that they handled it in one of the worst and most ineffective ways possible. Furthermore, once papal representatives and the pope himself began to even occasionally use them for public masses, any remaining doubt about their permissibility was eliminated in the mind of Catholics around the world.

Following the decree of 1957, Gothic vestments came to dominate the ecclesiastical landscape and their use for the last several decades has been essentially universal. Contrary to the expectations of the writer in America in 1910, it seems that the vast majority of priests in the mid-20th century did not adopt the Gothic with “heavy hearts” after all. It is also interesting that the lighthearted commentary from 1926 now appears to be extraordinarily prescient:

“The question of amplitude or non-amplitude in vestments will never, let it be hoped, rise, or descend, to schismatical proportions. There was a long dispute over the date of Easter. The war of the Vestments ought to be settled within a generation or two at the utmost.” [57]

And indeed it was.

NOTES (numeration continued from previous article):

%20-%20The%20Four%20Doctors%20of%20the%20Western%20Church,%20Saint%20Augustine%20of%20Hippo%20(354%E2%80%93430).jp.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)