St Patrick, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1746

Saint Patrick (385-461) is probably one of the Church’s best-known saints, at least in countries influenced by Irish emigration. But despite his popularity, the details of this his life are not well known. In this article, we survey the life and legacy of Saint Patrick and some of their surprising elements.

Ireland’s English Patron

Saint

Patrick, who was born in either Scotland or northern England, describes himself as both a Roman and a Briton (who were Celts). His father was a Roman decurion (a senator and tax collector) and a deacon, and his grandfather was a priest. As a youth, however, Patrick was a lukewarm believer, and at the age of fifteen he committed an unknown sin or cluster of sins in the span of an hour. [1] The misdeed(s) do not appear to have been a great crime, but, as we will see, they would come back to haunt him.

At the age of sixteen, Patrick’s life was changed forever when he and other members of his father’s household were abducted by Irish pirates and sold into slavery. (Sidenote: the Irish word for “pirate” is Foley, so you can thank my family for the gift of Saint Patrick to Ireland.)

Patrick spent six years in slavery, probably near the modern village of Killala in the northwest. He was charged with keeping watch over his master’s livestock and had to endure snow, frost, rain, hunger, and nakedness.

The experience was transformative. During that time, he grew in his love of God. He prayed day and night as he tended his master’s flocks, and the hardships he suffered did him no harm, for as he later came to realize, “the Spirit was burning hot” within him. [2] Eventually, he heard the voice of the Lord telling him that it was time to leave. Patrick obeyed and traveled two hundred miles to the east coast, where he found a ship bound for Britain. The problem was that he had no money for the voyage (a problem common among Irishmen), but as he was walking away the sailors invited him to join them.

After the ship landed (probably in Scotland), the crew and their holy passenger roamed the countryside desperately looking for food. Saint Patrick had been telling the sailors, who were pagan, about the infinite goodness and power of God, and so the starving company asked him why he was not praying for help. he told them that if they prayed with their whole hearts, God would answer their prayers. They did, and sure enough they fell upon a herd of wild boar. Guess who you’ll be praying to the next time you are hunting feral hogs.

Saint Martin of Tours, by The Master of Sierentz, 1440-50

Travels and Commission

Patrick was well traveled and well connected. Before returning to Ireland as a missionary, the Saint traveled from one end of the Continent to the other. His biography reads like a Who’s Who of contemporary Christian Europe. He studied under Saint Martin of Tours, was tonsured in the famous island monastery of Lérins in the south of France, ordained a priest by Saint Germanus of Auxerre, consecrated a bishop by Saint Maximus of Turin, and was given his commission to convert the Irish by Pope Saint Celestine I. Celestine gave him the job, by the way, because the first missionary to Ireland had fled in terror.

Patrick was probably not surprised to receive this commission. In his autobiography The Confession, he describes a vision that he had after coming back home to Britain. A man named Victoricus appeared to him carrying many letters from Ireland. Patrick opened one of them, which began with “The voice of the Irish.” As he read these words, he heard a multitude of natives from the place where he had been a slave say with one voice: “We beg you, holy boy, to come and walk again among us.” [3] his heart was deeply moved, and he could read no further.

Patrick’s Name

We do not know Patrick’s real name. When the Pope authorized him to evangelize Ireland, he prophetically named him Patricius or “father of citizens.” Before that, we are not entirely certain what he was called. A later biographer offers three options: Magonus, that is, famous; Succetus, that is, god of war; and Cothirthiacus, “because he served four houses of druids.”

Life

Patrick had a hard life. He was enslaved twice: the second time, possibly as a missionary, lasted two months. When Roman legions withdrew from Britain to protect other parts of the Empire, the region was destabilized. As he knew all too well, abductions and violence were rampant. Saint Patrick once excommunicated a leader and his soldiers who had the audacity to murder or enslave fellow Christians: some of the victims were so new to the Faith that they were still wearing their baptismal robes and the holy oil was still visible on their foreheads. Several times, local chieftains and the Druids had Patrick and his companions beaten, robbed, and enchained.

He was also scrupulous about his ministry and refused to accept gifts. The advantage of such a policy is that it steered clear of simony, but since it was often perceived culturally as an affront, it complicated his evangelizing efforts. Patrick deeply missed his home and family in Britain, and he wrote about how much he would have loved to visit his saintly friends in Gaul, but he felt obligated to remain in Ireland and do the Lord’s work.

His mission was, of course, a great success. According to his own testimony, he baptized thousands and lived to see some of Ireland’s future leaders become monks and nuns. A land that knew nothing of God and that had “served idols and unclean things,” as he put it, had now become “a people of the Lord.” [4] And yet, despite this success, Patrick writes his Confessio near the end of his life in an occasionally defensive tone. Apparently, he was beset by detractors who claimed that he had fabricated the story of his enslavement and who accused him of financial improprieties. He was also betrayed by a close friend to whom he had confided the sins he had committed at the age of fifteen. The friend mentioned this embarrassment to Patrick’s elders (seniores) in Britain, and they held this failing against him and his episcopate, bringing great sorrow to the Saint.

Activities

Stories about Saint Patrick’s labors in Ireland abound, although it is not always easy to separate fact from fiction. It is believed that he founded his main church in Armagh, which went on to become the head church in Ireland. He is also credited with founding churches and monasteries throughout the island. Numerous miracles are attributed to him, including restoring sight to the blind and raising nine people from the dead. He died on March 17, 461 in what is now known as Downpatrick, a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. His remains are preserved in Down Cathedral.

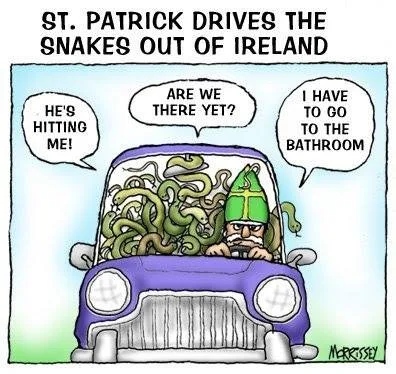

Shamrocks and Snakes

As a general rule, the more popular a legend is about Saint Patrick, the more it is dubious. Pace the Baltimore Catechism, Patrick most likely did not teach the Irish about the Trinity by using a shamrock (if he had, he would have been guilty of the heresy of partialism). According to one source, the earliest mention of the legend comes from (gasp!) English botanists in 1571; other accounts point to a travel diary by an English tourist visiting Ireland in 1684. And to complicate matters even more, the shamrock is not a botanically recognized species: the word seamróg (shamrock) is simply Gaelic for young clover. [5] Despite the shaky historical evidence, however, the shamrock is a fitting symbol of the Saint insofar as it is an inseparable symbol of the Irish people, whom he lovingly held in the palm of his hand.

Lutheran Satires, “Saint Patrick’s Bad Analogies”

Second, Patrick did not drive the snakes out of Ireland, at least not the reptilian variety. The last Ice Age had kept the sensitive, cold-blooded creatures from most parts of Europe, and when the earth began to warm up, they took advantage of ice bridges to reach places such as England. There was no ice bridge between Britain and Ireland, however, and so the snakes could not settle in the Emerald Isle. Ireland thus joined the ranks of Iceland, Greenland, New Zealand, and Antarctica in being perpetually snake-free. [6]

That said, it can be argued that Patrick did drive snakes out of Ireland There is a legend that he observed the Lenten fast of 441 A.D. on the mountain that now bears his name, Croagh Patrick or Reek Mountain in County Mayo, Ireland, and that afterwards he expelled the snakes by throwing his bell down the mountain. The bell was originally white, but it is now called the “Black Bell of Saint Patrick” because it pelted legions of demons who were disguised as black birds and venomous snakes. The snakes in question, then, were not reptiles but devils. To this day in Ireland, “Reek Sunday,” the last Sunday of July, commemorates the expulsion. Between 25,000 and 40,000 pilgrims climb Croagh Patrick each year.

Reek Sunday, date unknown

Moreover, according to another story, the same mountain was home to Corra, a frightening serpent-demon and the mother of Satan himself. Corra first sent her servants, the Sluagh, frightening minions in charge of the Wild Hunt who attacked Patrick in the form of black birds. After he banished them to the sea, Corra transformed herself into a fiery dragon and attacked him. The Saint won by clocking her with his bell, which drove her down the mountain slope. The demon is now trapped in a lake nearby (Lough Na Corra) and is allowed to ride the waves on dark and stormy nights. Just as Mary, the new Eve, crushes the head of the serpent through her Immaculate Conception, St. Patrick crushed the head of the serpent in Ireland through his evangelization.

The Last Judgment

Even after defeating the demonic, however, Patrick would not leave the mountain until he wrestled, Jacob-style, with God on behalf of his people. God kept sending an angel to give him more concessions, but the Saint persisting in praying and fasting until all his requests were met. They included: that many souls would be freed from Purgatory by his intercession; that the Saxons who were currently conquering the Britons never conquer the Irish; that the Irish remain Christian until the end of time; that just as the original Apostles will be judges of the twelve tribes of Israel (Mt. 19, 28), he (Patrick) will be judge of the entire Irish race at the end of time; and that the sea rise up and cover the Ireland seven years before the Last Judgment to spare the Irish the horrors of Doomsday. [7] If climate change ever drowns the island, start the countdown.

Patronages

Patrick has some unexpected patronages. He is obviously a patron saint of Ireland, and he has is also a patron of migrants because of his association with the Irish. He is a patron saint of engineers because he oversaw the construction of churches and, it is said, taught the Irish to build arches of lime mortar instead of dry masonry.

But the Apostle of Ireland is also the patron saint of Nigeria. In 1961, one year after Nigeria wrested its independence from Great Britain, the bishops of Nigeria (most if not all of them Irish) made Patrick the patron of the new nation. (That same day, the Republic of Ireland opened its embassy in the country, the first in Africa.) The bishops’ designation was not simply a case of personal preference. Irish missionaries had brought the Catholic faith to Nigeria in the nineteenth century while organizations like Saint Patrick’s Society for Foreign Missions provided education; at the same time, many Nigerians studied at universities in Ireland such as Trinity College Dublin, and some of them went on to occupy key posts in the Nigerian government. The Irish and Nigerians were natural allies, for both chafed at British colonial rule. And fittingly, after the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, Nigeria consumes more Guinness beer than any other nation, beating out the fourth-ranked U.S.A.

Saint Patrick Cathedral, Awka, Nigeria

I am also of the opinion that Patrick should be named the patron saint of surfers and water skiers. On one occasion, the Saint was transporting a large altar stone from the Continent to Ireland when the captain denied passage to a leper. Patrick threw his altar-stone into the sea, which miraculously floated, and had the leper sit on it. Leper and stone then cruised behind the ship for the entire journey.

Saint Patrick’s Day

Not every apostle to a nation is placed on the General Calendar, but the universal Church has celebrated March 17 as Saint Patrick’s feast day since the early 1600s, thanks to Father Luke Wadding, a native of Waterford and a Franciscan scholar. Wadding was the founder of the Irish Franciscan College of Saint Isidore in Rome and was on the committee to reform the Breviary. The pious priest celebrated the feast of Saint Patrick every year with great solemnity, and so it was only natural for him to persuade others to do so as well.

The celebration of Saint Patrick’s Day varies in different parts of the world. In the United States, the feast has been mixed in with Irish patriotism from an early age. Boston’s Irish Charitable Society sponsored the first organized celebration in 1737, and New York City began Saint Patrick’s Day parades in 1762. [8]

And yes, drunkenness has long been a feature of the Irish-American celebration. A New York Times report on the Saint Patrick’s Day festivities of 1860 is worth quoting at length:

It must be confessed that there were a great many persons very much intoxicated… The policemen had their hands full….An unbroken procession defiled through [the doorways of the detention center]… of officers in waiting on men and women in all stages of intoxication, from that balmy condition in which a man swears eternal friendship to all the world and is anxious to embrace everyone he meets, to that in which he is unable to walk without tying knots in his legs, though supported by an official friend on either side. Drunken women with infants in their arms, men argumentatively disposed to establish logically the fact of their own sobriety, and victims of pugilistic skill with too much color about the eyes, were yarded like cattle in the fenced inclosure [sic] for prisoners in the Court.[9]

In Ireland, by contrast, Saint Patrick’s Day has been a far more pious occasion. The day has been a holy day of obligation for centuries. There were no parades for the feast until the early 1900s, and all pubs were closed until recently. It is only within the past three decades that Saint Patrick’s Day has become as significant an affair in Ireland as it has been in the Irish diaspora for centuries.

In Nigeria, the Irish Embassy and the local Guinness breweries host different celebrations, while some Catholic parishes commemorate the day with rallies. Guinness is consumed as in other parts of the world, but it is followed by Isi ewu soup, a dish from the Igbo tribe made with goat’s head. Isi ewu, however, is a delicacy. For those who cannot afford it or a pint of Guinness, jollof rice, moi moi bean pudding, and meat straight from the wild (so-called “bush meat”) are consumed alongside locally produced palm wine. [10]

Today, Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated in more countries than any other national festival. Unexpected places include Russia, Malta, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia—and outer space. In 2011, U.S. astronaut Catherine Coleman, who is Irish on both sides, celebrated St. Patrick’s Day on the International Space Station by playing a century-old flute belonging to one of the Chieftains.

Other Customs

Pota Phadraig or “Patrick’s Pot” involves drinking a full measure of whiskey. The custom is also called “drowning the shamrock” because a clover leaf is sometimes floated on the drink; the shamrock is either consumed or tossed over the shoulder for good luck. According to legend, during his missionary travels Saint Patrick was given a glass of whiskey that was far from full by a stingy innkeeper (we’ll conveniently ignore the fact that whiskey was centuries away from being invented). Patrick told the man that a devil was living in his cellar which was causing him to be dishonest and that the only way the man could banish the devil was by filling each glass to its brim. When Patrick returned to the inn later, he saw that each cup was full and proclaimed the devil duly exorcised.

Drowning the Shamrock, 1852-1863

Ireland has been associated with the color green since at least the eleventh century, and the wearing of the green came into vogue as an assertion of Irish nationalism under British rule. Today it is customary to wear green clothes or a shamrock on Saint Patrick’s Day; naysayers are pinched for refusing to play along. That practice is yet another American novelty, which probably began in the early 1700s. The rationale is that since green makes one invisible to mischievous Leprechauns, pinching is a pointed reminder to clueless green-abstainers.

Centuries ago, on the other hand, the key thing in Ireland was to wear a cross, and often it was the color red. Saint Patrick’s Day badges, which are now all but extinct, were made of paper and decorated with a cross and other patterns.

Foods

In the minds of most Americans, corned beef and cabbage is the quintessential Irish meal to be served on Saint Patrick’s Day. The association, however, is only true for Irish Americans. In nineteenth-century Ireland, beef was expensive and pork was cheap, but in the U.S., it was the opposite. Irish immigrants learned of corned beef (which reminded them of Irish bacon) from their Jewish neighbors in the slums. The cut of beef, which is similar to brisket, is “corned” or salt-cured (the large grains of salt then in use were called corns). The Irish added cabbage because it was affordable, easy (it could be thrown into the same pot as the beef), and delicious.[11] In our recent cookbook Dining with the Saints, my co-author Father Leo Patalinghug offers an outstanding variation of this classic dish. Back in the old country, the traditional feast-day dinner consists of some kind of meat, a potato dish called colcannon, and Irish soda bread.

Corned Beef and Cabbage

Conclusion

In some respects, Saint Patrick’s cult is as coherent as an Irishman’s drunken expatiations. The legends about him and the current observances surrounding his feast day are often in tension with or are an outright contradiction of the holiness of the Saint (and we didn’t take about green beer and green rivers!). But what we know about Patrick is enough to strengthen our resolve not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Saint Patrick almost single-handedly converted an entire people to Christianity, a people that had been practicing a particularly dark and sinister religion. Those people went on to become a seedbed of saints, scholars, and missionaries—and, until recently, they were a model of unbreakable fidelity to the Catholic Faith. It is not just Ireland but the world that owes a debt of gratitude to the surprising and homesick British ex-slave who heard the voice of the Irish across the sea and answered it.

Michael P. Foley is the author with Father Leo Patalinghug of Dining with the Saints: The Sinner’s Guide to a Righteous Feast (Regnery, 2023).

An abridged version of this article appears in The Latin Mass magazine (Spring 2023). Many thanks to its editors for allowing its publication here.

Notes

[1] Patrick, Confessio 26.

[2] Confessio 16.

[3] Confessio 23.

[4] Confessio 41.

[5] MacConnell, Cormac. “Everything You Know about the Saint Patrick’s Day Shamrock is a Lie.” Irish Central. January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2023 from https://www.irishcentral.com/opinion/others/st-patricks-day-shamrock.

[6] Owen, James. “Snakeless in Ireland: Blame Ice Age, Not Saint Patrick.” National Geographic. August 16, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2023 from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/snakeless-in-ireland-blame-ice-age-not-st-patrick.

[7] See Moran, Patrick Francis Cardinal. "St. Patrick." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm.

[8] Cavanaugh, Ray. “The Irish Franciscan Who Gave Saint Patrick His Feast Day.” National Catholic Reporter. March 17, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2023 from https://www.ncronline.org/irish-franciscan-who-gave-st-patrick-his-feast-day.

[9] “Saint Patrick’s Day.” New York Times. March 19, 1860. p. 8.

[10] Egwu, Patrick. “Saint Patrick and Nigeria: The Irish Influence on an African country’s Catholic Mission.” Catholic World Report. May 17, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2023 from https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2020/05/17/st-patrick-and-nigeria-the-irish-influence-on-an-african-countrys-catholic-mission/. Many

thanks to Fr. Augustine Ariwaodo for his additional input.

[11] Glendon, Meaghan. “Learn All About the Origins of Corned Beef and Cabbage.” Westchester Magazine. March 17, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2023 from https://westchestermagazine.com/life-style/history/corned-beef-and-cabbage-origin/.

,_RP-F-F10671.jpg)