We never let August 30th pass without remembering the Blessed Cardinal Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster, who went to his eternal reward on this day in 1954, after serving as Archbishop of Milan for just over a quarter of a century. We have written about him many times on NLM, partly in connection with our interest in the Ambrosian liturgy, of which he was a great promoter, but also as one of the most important scholars of the original Liturgical Movement.

In 2018, we published a brief meditation of his on the value of praying the Office, which, to judge from viewing numbers and several requests for permission to reprint, was very much appreciated. This was taken from the account of Schuster’s final days included in the book Novissima Verba by Abp Giovanni Colombo, the cardinal’s successor-but-one in the see of St Ambrose. At the time of Schuster’s death, the latter was a simple priest, serving as both rector and professor of Italian literature at Venegono, the archdiocesan seminary which the cardinal had founded; it was he who who administered the last rites to Schuster. My translation of this incredibly moving piece certainly does not do justice to Abp Colombo’s magnificent Italian. Thanks to Nicola de’ Grandi for some of the pictures.

The call by which his secretary, Mons. Ecclesio Terraneo, informed us that His Eminence would come to Venegono for a period of rest was received in the seminary with a sense of joy, and also amazement. Joy, because it hardly seemed real that we could have time to enjoy the presence of the archbishop, whose visits were frequent, to be sure, but always accompanied by his eagerness to run off to other places and persons; amazement, and almost dismay, because the suspicion had arisen in us all that only a serious illness could have brought such a tireless shepherd to yield at last to the idea of taking a vacation, the first in 25 years of his episcopacy, and as it would prove, the last. …

… although nature and vocation had made him for the peace of prayer and study, more than for the turmoil of action, he never deceived himself (as to his duty), not even when old age and poor health would have urged greater moderation (in his activities). He had no wish to spare his energies, even when he was close to the end. He used to say “To be archbishop of Milan is a difficult job, and the archbishop of Milan absolutely cannot allow himself the luxury of being ill. If he becomes ill, it is better that he go at once to Paradise, or renounce his see.”

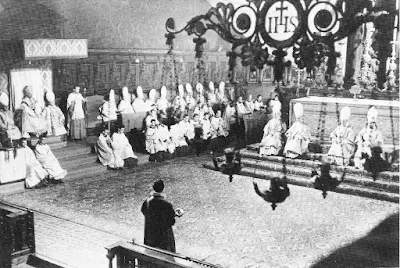

|

| Cardinal Schuster’s episcopal consecration, celebrated in the Sistine Chapel by Pope Pius XI, himself previously archbishop of Milan, on July 21, 1929. |

On the feast of the Assumption, the radio broadcast the noon Angelus recited by Pope Pius XII. Standing in the room where he took his meals privately, because he did not have the strength to reach the common dining room, while awaiting the Pope’s prayer, the archbishop heard along with us the joyful tolling of the bells of St Peter’s. At the sound, he looked at us with eyes full of emotion, and repeated twice, “The bells of my town, the bells of my town!” His voice was trembling; was it the sweet nostalgia of other occasions that called back to him to the long-ago solemnities of his childhood, or was it rather the sad understanding that he would never hear them again?

On the afternoon of August 18th, the high school seminarians and those of the theologate, who had come back to the seminary the day before… gathered on the tree-lined slope under the window of his apartment to see and greet the archbishop. Called by their youthful song, he appeared smiling on the balcony, and spoke to them with these words. “Here I am among you, on a forced rest; because I did not wish to pay the interest year by year, now I am forced to pay both interest and capital at once. You have asked for a memento from me. I have no memento (to give you), other than an invitation to holiness. It seems that people do not any longer let themselves be convinced by our preaching, but in the presence of holiness, they still believe, they still kneel and pray. It seems that people live in ignorance of supernatural realities, indifferent to the problems of salvation, but if a true Saint, living or dead, passes by, everyone runs to see him. Do you remember the crowds around the caskets of Don Orione or of Don Calabria? Do not forget that the devil has no fear of our playing fields and our movie theatres [1], but he does fear our holiness.” …

His days, which should have been passed in complete rest, were full of prayer, reading, decisions on the affairs of the diocese, and discussions. Someone said to him, “Your Eminence allows himself no rest. Do you want to die on your feet like St Benedict?” Smiling, he answered, “Yes.” This was truly his wish, but this was a matter of Grace, and thus it was God’s to grant.

It was only a few days before the 25th anniversary of his entry into the diocese. In the quiet sunsets of Venegono, he was beset by memories. How many labors and events, some of them tragic, did he have to confront after that serene morning of September 7th (1929), when, on the journey from Vigevano to Rho, he stopped the car half-way over the bridge on the Ticino river, got out, and kissed the land of St Ambrose on its threshold? That land had become his portion of the Church, the sacred vineyard of his prayerful vigils, of his austere penances, of his labor and his love, of his griefs both hidden and known, of all his life, and now of his death. From the end of the road he had traveled, looking back, he saw that he had passed through dangers of every sort, but felt that the hand of God had drawn him safely through fire and storm; above all, he was comforted by the thought that he had always had the affection and loyalty of his people. …

(Unedited footage of Cardinal Schuster’s installation as archbishop in Milan cathedral, unfortunately without soundtrack. Particularly noteworthy is the Latin plaque shown at the beginning, which set over the door of the cathedral, and starts with the words “Enter (‘Ingredere’, in the imperative,) Alfred Ildephonse Schuster.” Starting at 1:20, one sees the extraordinarily large crowd in the famous Piazza del Duomo, far too large for them all to enter the cathedral for the ceremony itself, many of whom have climbed up onto the large equestrian statue of King Victor Emmanuel II. From the YouTube archive of the Italian film company Istituto Luce.)

The archbishop spoke of the recent canonization of St Pius X, saying among other things, “Not every act of his governance proved to be completely opportune and fruitful. The outcome of one’s rule in the Church, as a fact of history, is one thing, whether for good or ill; the holiness that drives it is another. And it is certain that every act of St Pius X’s pontificate was driven solely by a great and pure love of God. In the end, what counts for the true greatness of the Church and Her sons is love.”

He spoke of St Pius X, but he was certainly thinking also of himself, in answer to his own private questions. Looking back upon his long episcopacy, the results could perhaps have made him doubt the correctness of some of his decisions, or the justice of some of his measures; he might perhaps have thought that he had put his trust in both institutions and men that later revealed themselves unworthy of it. But on one point, his conscience had no doubts: in every thought and deed, he had always sought the Lord alone, had always taken His rights with the utmost seriousness, and preferred them above everything and every man, and even above himself. As his spiritual father, Bl. Placido Riccardi, had taught him when he was a young monk, the Saint is set apart from other men because he takes seriously the duties which fall to him in regard to God. …

One morning, the door of his room was left half-opened; from without, one could see the cardinal sitting at the table in the middle of the room in the full light of the window. His joined hands rested on the edge of the desk, with the breviary open before them; his face, lit by the sun, was turned towards heaven, his eyes closed, and his lips trembled as he murmured in prayer. A Saint was seen, speaking with the invisible presence of God; one could not look at him without a shiver of awe. I remembered then what he had confided to me some time before concerning his personal recitation of the Breviary, in the days when he found himself so worn out that he had no strength to follow the sense of the individual prayers.

“I close my eyes, and while my lips murmur the words of the Breviary which I know by heart, I leave behind their literal meaning, and feel that I am in that endless land where the Church, militant and pilgrim, passes, walking towards the promised fatherland. I breathe with the Church in the same light by day, the same darkness by night; I see on every side of me the forces of evil that beset and assail Her; I find myself in the midst of Her battles and victories, Her prayers of anguish and Her songs of triumph, in the midst of the oppression of prisoners, the groans of the dying, the rejoicing of the armies and captains victorious. I find myself in their midst, but not as a passive spectator; nay rather, as one whose vigilance and skill, whose strength and courage can bear a decisive weight on the outcome of the struggle between good and evil, and upon the eternal destinies of individual men and of the multitude.” …

He had decided to end his stay and continue on his way. In vain did the doctors and all his close friends ask him to stay longer – he was set to depart from Venegono on August 30. “Neither rest nor the treatments have helped me: I might as well return to Milan. If death comes, it will find me on my feet, at my place and working.” And he would indeed depart that Monday, but on a different voyage.

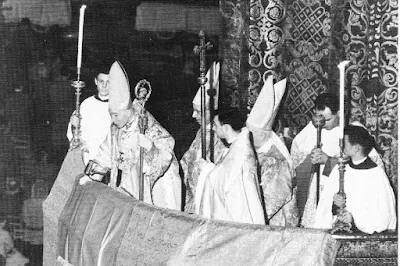

|

| Giovanni Cardinal Colombo, 1902-92; archbishop of Milan 1963-79. |

“I wish for Extreme Unction. At once, at once.”

“Yes, Your Eminence; the doctor will be here in a few moments, and if necessary, I will give you Extreme Unction.”

With a voice full of anguish, he replied, “To die, I do not need the doctor, I need Extreme Unction. … be quick, death does not wait.”

Meanwhile, Agostino Castiglioni, the seminary doctor, had arrived, and after seeing his illustrious patient, told us that his condition was very serious, but did not seem to be such that we should fear his imminent death.

Assisted by Mons. Luigi Oldani, by Fr Giuseppe Mauri, and Mons. Ecclesio Terraneo, I began the sad, holy rite. He spoke first, with a clear and strong voice: “In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti. Amen. Confiteor Deo omnipotenti...”

He followed every word with great devotion, answering every prayer clearly; at the right moment, he closed his eyes, and without being asked, offered the back of his hands for the holy oils.

When the sacrament has been given, sitting on the bed, he said with great simplicity, “I bless the whole diocese. I ask pardon for what I have done and what I have not done. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” He traced a wide Sign of the Cross before himself; then he lay down on the bed. The doctor at the moment realized that his heart was giving out.

“I am dying. Help me to die well.”

The signs of his impending death became more evident.

He groaned: “I cannot go on. I am dying.” …

He was told that in every chapel of the seminary, the various groups, the students of the theologate, the high school, the adult vocations, the oblate brothers, the sisters, were gathered in prayer and celebrating Masses for him. “Thank you! Thank you!”

He looked steadily upon each person who entered the room, as if he were trying to recognize someone for whom he was waiting. With his innate gentility, which did not fail even in his final agony, he invited those present to sit. “Please, have a seat!”

Again and again he repeated the prayers suggested to him, but at a certain point he said, “Now I can’t any more. Pray for me.” …

At 4:35, he let his head fall on the pillow, and groaned. His face became very red, then slowly lost its color. From the other side of the bed, the expression of the doctor, who was holding his wrist, told us that he no longer lived upon the earth. The heart of a Saint had ceased to beat. …

None of those present felt that they had attended three hours of agony, but rather, at a liturgy of three hours’ length. Three hours of darkness, but a darkness filled with the hope of the dawn that would rise in the eternal East. Three hours of suffering, but a suffering permeated by waves of infinite joy coming rapidly on. He spoke no uncontrolled words; his suffering, which was great, (he said “I cannot go on! I cannot go on!” several times), was indicated by quiet laments, as if in dying he were not living through the sufferings of his own flesh and spirit, but rather reading those of the Servant of the Lord in the rites of Holy Week. [2] He made no uncontrolled movements; his translucent hands, his arms, his head, all his slender body, held to the hieratic gestures of a pontifical service.

The archbishop’s death was in no way different from those of the ancient giants of holiness on whose writings he had long meditated, with such fervor as to become familiar with their very thoughts, their feelings and their deeds. A year before he died, describing their death in the Carmen Nuptiale [3], without knowing it, he prefigured his own death. “The death of the ancient Fathers was so dignified and serene! Many holy bishops of the Middle Ages wished to breathe their last in their cathedral, after the celebration of the Eucharist, and after exchanging the kiss of peace with the Christian community. Thus does St Gregory the Great describe the death of Cassius, bishop of Narni, of St Benedict, of St Equitius, etc. In the Ambrosian Missal, the death of St Martin is commemorated as follows: Whom the Lord and Master so loved, that he knew the hour in which he would leave the world. He gave the peace to all those present, and passed without fear to heavenly glory. [4] But what was it that made the death of these Saints so precious in the sight of God (Psalm 115, 6) and of the Church? In the fervor of their Faith, they rested solidly on the divine promise, and so set their feet on the threshold of eternity. ‘Rejoicing in the sure of the hope of divine reward….’ These are the words of St Benedict.” [5]

The Carmen Nuptiale was a truly prophetic swan song. Speaking of St Benedict, Schuster had written, “After the Holy Patriarch’s death, some of his disciples saw him ascend to the heavenly City by a way decorated with tapestries, and illuminated with candlesticks. This was the triumphal way by which the author of the Rule for Monks and the Ladder of Humility passed.”

The street which descends from the hill of the seminary, passing through Tradate, Lonate Ceppino, Fagnano Olona, Busto Arsizio, Saronno, and comes to Milan, was the triumphal way decorated with tapestries, illuminated by the blazing sun, on which not just a few disciples, but crowds without number, watched him pass, one who out of humility had refused all celebration of his 25th year of his episcopacy.

Who drove all those people, on that August 31st, to line the streets? Who drew the workers to come out of their factories, along the city walls? Who brought those men and women together, waiting for hours for the fleeting passage of his casket? Who drove the mothers to push their little ones towards that lifeless body? Why did they all make the Sign of the Cross, if his motionless hand could not lift itself to bless them? What did those countless lips murmur, what was it that they wished to confide to a dead man, or ask of him?

He himself gave the answer fifteen days before to the seminarians, speaking from the balcony of his rooms. “When a Saint passes by, everyone runs to see him.”

[2] Isaiah 53, known as the Song of the Suffering Servant, is read at the Ambrosian Good Friday service ‘post Tertiam’, before the day’s principal account of the Lord’s Passion.

[3] “Carmen Nuptiale – Wedding Song” is the title of a poem on the monastic life written by the Bl. Schuster in the year before he died.

[4] The Transitorium (the equivalent of the Roman Communio) of the Ambrosian Mass of St Martin. “Quem sic amavit Magister et Dominus, ut horam sciret qua mundum relinqueret. Pacem dedit omnibus adstantibus: et securus pergit ad caelestem gloriam.”

[5] The Rule of St Benedict, chapter 7. “Securi de spe retributionis divinae... gaudentes.”

_%C3%89glise_Saint-Sulpice_Baie_08_Fichier_16.jpg)