March 21 is the

dies natalis of one of the most influential of all saints, Benedict of Nursia, Patriarch of Western Monasticism and Co-Patron of Europe. Highly pertinent to this blog’s concerns are the many profound liturgical lessons contained in the

Holy Rule. Today I would like to consider a point from chapter 5.

According to St. Benedict, the root of humility is that a man must live not by his own desires and passions but by the judgment and bidding of another:

ambulantes alieno judicio et imperio. When St. Benedict comes around to ordering the monastic liturgy, he makes continual reference to how things are done elsewhere: the psalms prayed by our fathers, the Ambrosian hymn, the canticles used by the Church of Rome. Even when fashioning his monastic cycle of prayer, he is constantly looking to the models already in existence. In like manner, chapter 7 warns us against “doing our own will,” lest we become corrupt and abominable.

This is the true spirit of liturgical conservatism, piety towards elders, and the imitation of Christ. We are not the ones who determine the shape of our worship; we receive it in humility as an “alien judgment” that we make our own. To do otherwise is to put the axe to the tree of humility. (St. Benedict allows for a redistribution of the psalms,

as long as monks rigorously hold to the principle of praying the full psalter in one week. Therefore it would not conflict with humility for a monastic community to make

some adjustments to the cycle of psalms, yet it would smack of temerity to reject the most ancient and stable pillars of the office, such as the praying of the whole psalter each week, and, to take a couple of specific examples, Psalms 109–112 for Sunday Vespers and Psalms 66, 50, 117, 62, and 148–150 for Sunday Lauds.)

Liturgical prayer has always been the foremost way of inculcating submission to Christ and His Church, so that we can learn His ways, and assimilate His prayer, and drink of

His wisdom—which will certainly not be something we ourselves could have “cooked up.” Thus we take

His yoke upon us…the yoke of tradition.

Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, it was taken for granted in Catholic circles that it is a special

perfection of the sacred liturgy to be fixed, constant, stable, an immovable rock on which to build one’s spiritual life. The liturgy’s numerous and exacting rubrics were understood as guiding the celebrant along a prayerful path of submissive obedience, in which he could submerge his personality into the Person of Christ and merge his individual voice with the chorus of the Church at prayer. The formal, hieratic gestures transmitted an eternally fresh symbolism while limiting (if not eliminating) the danger of subjectivism and emotionalism. The priest or other minister was conformed to Christ the servant, who came not to do His own will but the will of Him who sent Him; he is commanded what to speak and what to do; he never speaks of himself.

The Father who abides in the Son does the work of the Son, and the Son who abides in the priest likewise does the work of the priest. In this way, even as the Son was “emptied of glory” in taking on the form of a slave, so, too, is the priest who enters His

kenosis, sharing the hiddenness, humiliation, passion, and death of Christ. We may even say that the priest imitates and participates in the descent of Christ into hell by offering the Holy Sacrifice for the release of souls in Purgatory, which has a certain resemblance to the limbo of the fathers.

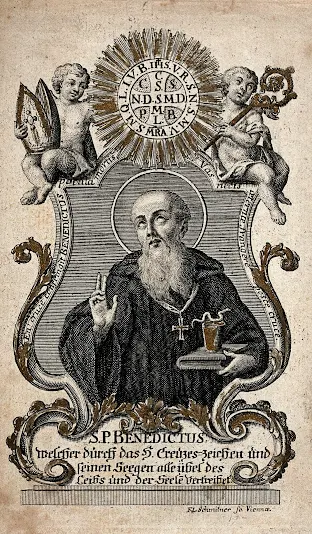

|

| The last Holy Communion of St. Benedict |

Our Lord, the great High Priest of the New Covenant said: “I cannot do anything of myself” (Jn 5:30). Here we have perhaps the most radical statement of the priest’s being tethered to the liturgy. It is a tethering so complete that he may truthfully say: “I

cannot do otherwise.” If he thinks or acts otherwise, he has not yet become a slave, in imitation of the One who assumed the likeness of a slave. Worse, if he is

allowed to do otherwise by a liturgical book, that book is a smudged and fractured mirror that does not reflect the Word.

This is why we ought to be unnerved by one of the most notable novelties in the Missal of Paul VI and in all the revised liturgical books, namely, that by which the celebrant is given many options among which he may choose, as well as opportunities for crafting his own speech: “in these or similar words.”

[1] Confronted with such a phrase, one might legitimately ask: “How similar is similar?” In reality, the word of the liturgy and the word of the minister ought to be

homoousios, of one and the same substance, not

homoiousios, of a similar substance.

In the action of selecting options and extemporizing texts, the celebrant no longer perfectly reflects the Word of God who, as the perfect Image of the Father, receives His words and does not originate them, who does the will of another and not His own will. The elective and extemporizing celebrant does not show forth the fundamental identity of the Christian: one who receives and bears fruit, like the Blessed Virgin Mary; one who conceives with no help of man, by the descent of the Spirit alone.

[2]Instead, he adopts the posture of one who originates; he removes this sphere of action from the master to whom he reports; he carves out for himself a zone of autonomy; he denies the Lord the privilege of commanding him and deprives himself of the guerdon of submission; for a moment he leaves the narrow way of being a tool and steps on to the broad way of being somebody. He becomes not only an actor but a playwright; his

free choice as an individual is exalted into a principle of liturgy. He joins the madding crowd that says, in the words of the Psalmist:

linguam nostram magnificabimus, labia nostra a nobis sunt; quis noster dominus est? “We will magnify our tongue; our lips are our own; who is Lord over us?” (Ps 11:5).

But since free choice is antithetical to liturgy as a fixed ritual received from our forebears and handed down to our successors, choice tends rather to be a principle of distraction, dilution, or dissolution in the liturgy than of its well-being. The same critique may be given of all of the ways in which the new liturgy permits the celebrant an indeterminate freedom of speech, bodily bearing, and movement. Such voluntarism strikes at the very essence of liturgy, which is a public, objective, formal, solemn, and common prayer, in which all Christians are equally participants, even when they are performing irreducibly distinct acts. The prayer of Christians belongs to everyone in common, which means it should not belong to anyone in particular. The moment a priest invents something that is not common, he sets himself up as a clerical overlord vis-à-vis the people, who must now submit not to a rule of Christ and the Church, but to the arbitrary rule of this individual.

In the liturgy

above all, we must never speak “from ourselves,” but only from Christ and His beloved Bride, the Church.

The deepest cause of the missionary collapse of the Church in the Western world is that we have lost our institutional and personal subordination to Christ the High Priest, the principal actor in the liturgy, the Word to whom we lend our mouth, our hands, our bodies, our souls. For the past fifty years it has

not been perfectly clear that we are in fact ministers and servants

of another, intelligent instruments wholly at His disposal. On the contrary, the opposite message has been promoted over and over again,

ad nauseam, whether in words or in deeds: we have “come of age,”

we are shaping the world, the Church, the Mass, the entire Christian life, according to our own lights, and for our own purposes. It is not difficult to see both that this is an inversion of the preaching of Christ and of the tradition of the Church

and that it cannot produce renewal, but rather, confusion, infidelity, boredom, and desolation. We see here an exact parallel to what has happened with marriage: when so-called “free love” entered into the picture, out went committed love and heroic sacrifice, and in came lust, selfishness, dissatisfaction, and an unspeakable plague of loneliness. “Without me, you can do nothing” (Jn 15:5). In the realm of sexual morality as in the realm of liturgical morality, we have given a compelling demonstration of what we can accomplish without Christ and without His gift of tradition—namely, nothing.

As if the Church had suddenly developed an autoimmune disease, churchmen in the twentieth century turned against ecclesiastical traditions, against greatness in music, art, and architecture, against rites and ceremonies, in a sterile love-affair with nothingness. We have witnessed an inbreaking of the underworld, an influx of demonic energy and chaos. Rejecting one’s past is rejecting oneself; this is what makes the comparison to an autoimmune condition apt. It does no good to pretend that we are dealing with anything less harmful than this, less dangerous, or less in need of exorcism.

I believe that we are much more on our guard now: the enemy of human nature has shown his cards and we are better prepared to detect his wiles. I would include in this category the flurry of thinking and writing that has taken place in recent years about the inherent limits of papal authority, the obligation of the pope to act as servant of the servants of God rather than an oriental (or South American) despot, and the inner connection between liturgy, dogma, and morality. As time goes on, I have no doubt that the truth of the axiom

lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi will be made manifest in a blazing light of obviousness that will swell the ranks of Catholic traditionalists and expose the modernism of their opponents past all gainsaying.

The liturgical humility taught and practiced by St. Benedict will be, once again, as it had already been for so many centuries of Church history, a vital force in the restoration of worship for which we pray and labor.

NOTES

[1] See Rev. Paul Turner,

In These or Similar Words: Praying and Crafting the Language of the Liturgy (Franklin Park, IL: World Library Publications, 2014). A synopsis may be found at

http://paulturner.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ml-in-these-or-similar-words.pdf.

[2] See “The Spirit of the Liturgy in the Words and Actions of Our Lady” in Peter Kwasniewski, Noble Beauty, Transcendent Holiness: Why the Modern Age Needs the Mass of Ages (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2017), 53–87.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)