Wednesday, August 20, 2025

Cistercian Chants for the Feast of St Bernard

Gregory DiPippoThursday, August 14, 2025

Music for First Vespers of the Assumption

Gregory DiPippo| O quam glorifica luce coruscas, Stirpis Davidicae regia proles! Sublimis residens, Virgo Maria, Supra caeligenas aetheris omnes. |

O with how glorious light thou shinest, royal offspring of David’s race! dwelling on high, O Virgin Mary, Above all the regions of heaven. |

| Tu cum virgineo mater honore, Caelorum Domino pectoris aulam Sacris visceribus casta parasti; Natus hinc Deus est corpore Christus. |

Thou, chaste mother with virginal honor, prepared in thy holy womb a dwelling place for the Lord of heaven; hence God, Christ, was born in a body. |

| Quem cunctus venerans orbis adorat, Cui nunc rite genuflectitur omne; A quo te, petimus, subveniente, Abjectis tenebris, gaudia lucis. |

Whom all the word adores in veneration, before whom every knee rightfully bends, From whom we ask, as thou comest to help, the joys of light, and the casting away of darkness. |

| Hoc largire Pater luminis omnis, Natum per proprium, Flamine sacro, Qui tecum nitida vivit in aethra Regnans, ac moderans saecula cuncta. Amen. |

Grant this, Father of all light, Through thine own Son, by the Holy Spirit, who with liveth in the bright heaven, ruling and governing all the ages. Amen. |

The Sarum and Dominican Uses also have a special Magnificat antiphon for First Vespers of the Assumption, much longer than those typically found in the Roman Use.

Aña Ascendit Christus super caelos, et praeparavit suae castissimae Matri immortalitatis locum: et haec est illa praeclara festivitas, omnium Sanctorum festivitatibus incomparabilis, in qua gloriosa et felix, mirantibus caelestis curiae ordinibus, ad aethereum pervenit thalamum: quo pia sui memorum immemor nequaquam exsistat. – Christ ascended above the heavens, and prepared for His most chaste Mother the place of immortality; and this is the splendid festivity, beyond comparison with the feasts of all the Saints, in which She in glory and rejoicing, as the orders of the heavely courts beheld in wonder, came to the heavenly bridal chamber; that She in her benevolence may ever be mindful of those that remember her.

Thursday, July 17, 2025

The Church of Our Lady in Roermond, the Netherlands

Gregory DiPippoMy thanks to a friend, Fr Mark Woodruff, for sharing with us these pictures which he took during a recent visit to the church of Our Lady in Roermond, in the south-eastern Dutch province of Limburg. It was founded as part of a Cistercian women’s monastery in the early 13th century, and is therefore commonly known as simply “the Munsterkerk - the monastery church.” (None of the monastic buildings remain.) It owes its current external appearance to a major restoration done by a local architect named Pierre Cuypers from 1863-90. Cuypers also did a major neo-Gothic renovation of the interior, but much of his work was removed in a subsequent restoration of 1959-64, which aimed to return the building to something more like the sparer original late Romanesque style (or what the restorers imagined to be such.)

Tuesday, June 17, 2025

The Cisterican Abbey of Salem in Southern Germany

Gregory DiPippoOur Ambrosian writer Nicola de’ Grandi recently visited the abbey of Salem in southern Germany, about 18 miles to the west of Ravensberg, half that distance from the city Constance to the south-west. It was founded as a Cistercian house within the lifetime of St Bernard, in the 1130s, and quickly grew to become of the largest and most important abbeys in all of the German Empire; by the end of the 13th century, the community had 300 members. The present Gothic church was begun in 1285, and consecrated in 1414, a simple but imposing structure, and in fact the largest Cistercian church in the world, very much in keeping with the austerity which characterized the order in its early centuries. However, as is the case with many Cistercian churches, the interior was completely redecorated in the much more elaborate Baroque style after the Counter-Reformation, in the 1620s.

Sunday, November 03, 2024

The “Prophecies” of St Malachy

Gregory DiPippoIn Ireland, today is the feast of St Malachy, one of the great ecclesiastical reformers of the 12th century. He served for a time as Primate of Ireland in the very ancient See of Armagh, established by St Patrick himself, but later resigned that office, and ended his life as bishop of Down. The revised Butler’s Lives of the Saints sums up his career by likening him to St Theodore of Canterbury, who lived half a millennium before him, and gave a permanent form to the organization of the Church in England. His feast is also kept by various congregations of canons regular, since the reform movement of which he was such an important figure was very much concerned with restoring discipline to the lives of such congregations, and cathedral canons as well. He was a close personal friend of St Bernard, and actually died in his arms after a brief illness while visiting Clairvaux Abbey, on All Souls’ Day of 1148. Bernard was so convinced of Malachy’s sanctity that when celebrating his funeral, he sang the Post-Communion prayer of a Confessor Bishop instead of that of the Requiem Mass; he later wrote his biography, and for these reasons, the Cistercians also have Malachy on their calendar. Bernard’s judgment was formally confirmed by Pope Clement III in 1190; Ireland had, of course, a great many Saints before then, but Malachy was the very first to be formally recognized as such by a Pope.

|

| A statue of St Malachy on the outside of Armagh Cathedral. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Andreas F. Borchert, CC BY-SA 4.0) |

|

| The Papal coat-of-arms of Pope Leo XIII |

Saturday, February 03, 2024

A Cistercian “The Great Silence” From 1959

Gregory DiPippoThe YouTube channel of the Cistercian abbey of the Holy Cross in Itaporanga, Brazil (state of São Paulo), recently posted a beautiful video about the daily life of the Trappist abbey of Mariawald in western Germany, originally aired on a German television channel on March 22, 1959, the day after the feast of St Benedict. I don’t know if the creators of the famous film about the Grand Chartreuse “Die große Stille” (inexplicable called “Into Great Silence” in English, rather than “The Great Silence”) ever saw this, but it would not surprise me if they did and were inspired by it. Just as the Carthusians really take their time in singing the Divine Office, their documentary has a run time of over 2½ hours, and long (but beautiful, of course) stretches of not-much-happening. The Cistercians, on the other hand, sought to restore a balance between the “ora” and the “labora” of the Benedictine motto, which (as they saw it) their Cluniac predecessors has upset very much in favor of the former, and modified the Office so that it could be done decorously, but more quickly. Likewise, this film gives us a pretty comprehensive view of their life in just under a half-hour. (The narration is in German, by the way, but English subtitles are provided.)

At 16:30, the video shows the community assembling for the conventual Mass, and at 17:10, the soundtrack is the introit for Easter Sunday, so presumably the Mass shown is that of the previous Easter, although the narration does not say so. The Mass is followed (at 19:34) by the giving of tonsure and minor orders, with a good explanation of what these orders mean, and an interesting (and correct) underlying assumption that these ancient customs are in fact still both meaningful and perfectly comprehensible to Modern Man™. At 21:15, we see footage of a Corpus Christi procession through the abbey cloister, something which is also seen in The Great Silence. At 23:50, we see a very moving custom of the Order: when a member of the community dies, for 30 days, his place is still set at the table, with a black crucifix set in front of it, and his portion of the meal distributed to the poor. At 24:32, we see some examples of the Cistercian sign language, which was used to keep the amount of talking to a necessary minimum.Sunday, August 20, 2023

A Medieval Hymn of St Bernard

Gregory DiPippoThere are some interesting things to note. The hymn is an acrostic, the first letters of each stanza spelling his name BERNARDVS. The meter is the iambic dimeter, that of the original hymns of St Ambrose and other early Christian poets, short and long syllables alternating four times for a total of eight. (Substitutions are very common, especially since vowel quantities were already weakened in the 5th century, and hardly perceived as such in the High Middle Ages.) As such, it could in theory be sung in any one of a great many melodies, and other common hymns in this meter were often sung with different music from one church to another. However, it was an essential characteristic of the medieval Cistercians to keep a strict uniformity of observance in all their houses, and it is almost certain that they would have all used the same music.

The words of the third stanza “By the figure of a dog with a red back” refer to an episode recorded in the life of St Bernard. When his mother Aleth was pregnant with him (the third of her seven children, of whom four others are Blesseds), she dreamt that she was carrying a barking white dog with some red hair on its back. A religious man whom she consulted explained this dream to mean that the child she bore would be like the dogs mentioned in Psalm 67, “The tongues of your dogs lick the blood of their enemies”, guarding the house of God against its enemies, a preacher, and a healer of souls. This latter idea derives from St Gregory the Great’s symbolic interpretation of the dogs that licked the sores of Lazarus (hom. 40 in Evang.), in a passage which is read in the Roman Breviary on Thursday of the second week of Lent. “A dog’s tongue heals the sore which it licks; and so do holy teachers, when they instruct is in the confession of our sins, touch the sores of our souls by their tongues (i.e. their speech).” The following stanza refers to a vision of the Child Jesus which Bernard himself had when he was a boy, and fell asleep while waiting with his family to go out to Matins and the Midnight Mass of Christmas.

|

| Christ Embracing St Bernard, ca. 1625, by Francisco Riablta (1565-1628). Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Splendor paternae gloriae – an original hymn of St Ambrose himself, which the

Cistercians sing at Sunday Lauds, the Roman Office at Monday Lauds.

Jesu, nostra redemptio – from the feast of the Ascension, pre-Urban VIII

Conditor alme siderum – from Vespers of Advent, pre-Urban VIII

O lux, beata Trinitas – Saturday Vespers, pre-Urban VIII

Deus, creator omnium – the Ambrosian hymn for Sunday Vespers

Summi largitor praemii – a hymn for Lent sung by the Cistercians at Matins;

also used at Sarum, but not in the Roman Office.

Magnum salutis gaudium – processional hymn for Palm Sunday

Aeterna Christi munera – Matins hymn of the Apostles.

Beata nobis gaudia – Lauds hymn of Pentecost.

In addition, the first line of the second stanza, “Exsultet caelum laudibus”, is the title of the pre-Urban VIII version of the Vespers hymn of the Apostles. (Like all the religious orders that retained their own Uses of the Divine Office, the Cistercians never adopted Pope Urban VIII’s reform of the hymns.)

The difficulty of this trick is to integrate the titles into the words of a new composition in a new sense. Some of the expressions in the vocative case, such as “Jesu, nostra redemptio,” could be interchanged with any of the others, (I do not say this as a critique of the author; medievals valued originality far less than we do,) but the last three are particularly well chosen.

The Cistercians were founded at the very end of the 11th century as “strict constructionalists” of the original Rule of St Benedict, which they felt had been unhappily compromised by later developments and customs that emerged within the Cluniac monastic empire. The term which St Benedict uses for “hymn” in the Rule (capp. 9, 12, 13 and 17) is “ambrosianum”, since it was St Ambrose who first introduced the use of hymns into the West. This led the Cistercians to the believe that St Benedict’s original intention was not merely that monks should sing “a hymn” at certain Hours, but that they should use the specific corpus of hymns used by Ambrose himself. This corpus would be found, as they thought, in the Ambrosian Divine Office; they therefore sent people to Milan to copy out the Ambrosian hymnal then in use, and bring it back to Citeaux. It was incorporated into their Office to the despite of many hymns which at that point had long been in general use within the broad liturgical family of the Roman Rite. This was very controversial, even for an age in which there was a great deal of liturgical variation, and the Order was eventually pressured into adopting the traditional corpus of hymns, with some variations. This is why some of the original Ambrosian hymns such as “Splendor paternae gloriae” are given a more prominent place within the Cistercian Office than they were elsewhere.

Posted Sunday, August 20, 2023

Labels: Ambrosian Rite, Cistercians, hymns, Liturgical History, Medieval Liturgy

Monday, March 27, 2023

How Cistercians Can Help Us Reimagine the Ceremony of the Washing of Feet

Peter KwasniewskiI would like to suggest that in regard to the Holy Thursday mandatum ceremony, we can learn a valuable lesson from the Cistercian tradition — one that could resolve even this particular dispute in a surprisingly sympathetic manner.

First, we must recognize that Our Lord's washing of the feet has a double aspect to it, which, it seems to me, accounts for some of the confusion we have managed to introduce by not thinking through how these two aspects are related. One aspect is the washing of the apostles’ feet at their ordination and the first Mass. Here, the accent is definitely placed on the apostolic college as the kernel of the new ministerial priesthood of the new covenant. The other aspect is the washing of the feet as a symbol of serving one’s fellow man in general, even as Christ came not to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.

Thus we have something of a paradox here: a symbolic action of universal application is nevertheless being given at a very particular event in salvation history with a very special group of men—not just any human beings, not just any male individuals, but the first priests and bishops of the Church. The Virgin Mary was holier than all of them put together, she offered her Son most perfectly the next day at the foot of the Cross, and she guided the nascent Church in profound ways we will understand only in heaven. And yet she was not called upon to offer the Eucharistic sacrifice nor to govern local churches, as the Apostles and their successors did; nor was she among the men whose feet were washed at the Last Supper.

This tension in the mandatum between the universal charity symbolism and the particular apostolic/priestly symbolism makes it necessary to choose ONE or the OTHER as the prime symbol. Yet there is an assymetrical relationship between these. If you mix in the women, you are opting for the universal charity message and excluding the ordination message; whereas if you simply have men, as the rubrics specify, you are opting for a reenactment of what Christ did that evening at the first Mass, but you are not excluding the charity symbolism. After all, the very heart of the sacrifice of Christ was His burning charity for God and man, and this is the love the apostles, as His priests, are to carry into the world. In any case, the way the ceremony is done should not, as it were, garble the message so that one ends up severing the universal message from its original sacramental context.

Here is where the Cistercian tradition can be so helpful. Historically, these related but distinct aspects of the Holy Thursday washing of the feet were highlighted in analogous but still separate monastic ceremonies, as Terryl N. Kinder explains:

While many activities related to water took place in the gallery nearest the fountain, the mandatum was performed in the collation cloister. The weekly mandatum, or ritual washing of the feet, takes its name from the commandment of Jesus (John 13:34), which was also the text of an antiphon sung during the ceremony: “Mandatum novum . . .” (“A new commandment I give you . . .”). The ritual was a reminder of humility and also of charity toward one’s neighbors, whether those in the community or those outside. It was obviously inspired by Christ washing the feet of his disciples, and it was commonly practiced in the early church as a simple act of charity, recommended by Saint Paul (1 Tim. 5:10).

The community mandatum took place just before collation and Compline on Saturday afternoon, and, as specified in chapter 35 of the Rule of Saint Benedict, the weekly cooks—incoming and outgoing—performed the ceremony. The cooks who were leaving their week’s duty were responsible for heating the water in cold weather. The monks sat along the benches in this gallery, and the ritual began when the abbot (or cantor in the abbot’s absence) intoned the antiphon Postquam. After the abbot took off his shoes, the community followed, but as foot modesty was very important, the brothers were instructed to keep their bare feet covered at all times with their cowls. The senior (in monastic rank) of the two monks entering his week’s kitchen service washed the abbot’s feet first, while the junior incoming kitchen brother dried his feet; this pair continued washing and drying the feet of all the monks sitting to the left of the abbot. At the same time the senior of the cooks leaving his weekly service washed the feet of the brothers to the abbot’s right, the junior outgoing cook drying; the pair finishing first went to the other side to help. The cooks then washed their hands along with the vessels and towels, and everyone put their shoes back on before the collation reading began.

On Holy Thursday preceding Easter, this ceremony had a special form, the mandatum of the poor. The porter chose as many poor men from the guesthouse as there were monks in the monastery, and these men were seated in this cloister gallery. The monks left the church after None, the abbot leading and the community following in order of seniority, until each monk was standing in front of a guest. The monks then honored the poor men by washing, drying, and kissing their feet and giving each one a coin (denier) provided by the cellarer. Later the same afternoon, the community mandatum was held, and it, too, had a special form on this day. In imitation of Christ washing the feet of the twelve disciples, the abbot washed, dried, and kissed the feet of twelve members of the community: four monks, four novices, and four lay brothers. His assistants then performed this ceremony for the entire community, including all monks from the infirmary who were able to walk, and all lay brothers.

We see, then, that the activities carried out in the gallery parallel to the church were activities of a spiritual nature—much like those carried out in the church itself. In every case they emphasized the Christian life in community, whether directed inwardly to oneself (the collation reading) or, in the mandatum, shared among others. The weekly mandatum recalled the unity-in-charity of the monastic community; the Holy Thursday mandatum linked that community to Christ and his disciples; and the mandatum of the poor symbolized the responsibilities of the community to the world of poverty and suffering beyond the abbey walls.[1]

It seems to me that we may be victims of a too limited imagination when it comes to the way the liturgy (and the rich symbols of the liturgy) can spill out into parish activities, outreach programs, or other domains of Catholic life. Are we trying to jam everything into the Mass? We will certainly end up making a mess of it, if that's the line of thinking we are following. Whereas if we allow the powerful deeds of Christ to sink into our consciousness, we will, like the Cistercians, develop a plethora of ways to express the inexhaustible richness of the Gospel, like streams branching off of a river.

NOTE

[1] Terryl N. Kinder, Cistercian Europe: Architecture of Contemplation (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans; Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 2000), 136-37. To read more about how the Cistercians at Heiligenkreuz live out this practice even today, see this article by Fr. Edmund Waldstein, O.Cist.

Wednesday, November 03, 2021

The “Prophecies” of St Malachy

Gregory DiPippoIn Ireland, today is the feast of St Malachy, one of the great ecclesiastical reformers of the 12th century. He served for a time as Primate of Ireland in the very ancient See of Armagh, established by St Patrick himself, but later resigned that office, and ended his life as bishop of Down. The revised Butler’s Lives of the Saints sums up his career by likening him to St Theodore of Canterbury, who lived half a millennium before him, and gave a permanent form to the organization of the Church in England. His feast is also kept by various congregations of canons regular, since the reform movement of which he was such an important figure was very much concerned with restoring discipline to the lives of such congregations, and cathedral canons as well. He was a close personal friend of St Bernard, and actually died in his arms after a brief illness while visiting Clairvaux Abbey, on All Souls’ Day of 1148. Bernard was so convinced of Malachy’s sanctity that when celebrating his funeral, he sang the Post-Communion prayer of a Confessor Bishop instead of that of the Requiem Mass; he later wrote his biography, and for these reasons, the Cistercians also have Malachy on their calendar. Bernard’s judgment was formally confirmed by Pope Clement III in 1190; Ireland had, of course, a great many Saints before then, but Malachy was the very first to be formally recognized as such by a Pope.

|

| A statue of St Malachy on the outside of Armagh Cathedral. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Andreas F. Borchert, CC BY-SA 4.0) |

|

| The Papal coat-of-arms of Pope Leo XIII |

Friday, August 20, 2021

Cistercian Chants for the Feast of St Bernard

Gregory DiPippoMonday, March 22, 2021

The Feast of St Benedict 2021

Gregory DiPippoIn places where St Benedict is kept as a patron, including all Benedictine houses of whatever order, his feast is transferred to today, since yesterday was Passion Sunday, which can never be impeded.

|

Saints Benedict and Bernard, by Diogo de Contreiras, 1542; painted for the Cistercian convent of Santa Maria de Almoster in Portugal. (Public domain image from Wikimedia.)

|

|

| The first two pages of the Rule of St Benedict, with the Prologue to be read on March 21st, from a Cistercian Martyrology printed at Paris in 1689. |

Posted Monday, March 22, 2021

Labels: Benedictines, Cistercians, feasts, Rule of St. Benedict, St. Benedict

Saturday, August 29, 2020

A First Mass in Poland

Gregory DiPippoThursday, August 20, 2020

A Medieval Hymn of St Bernard

Gregory DiPippoThere are some interesting things to note. The hymn is an acrostic, the first letters of each stanza spelling his name BERNARDVS. The meter is the iambic dimeter, that of the original hymns of St Ambrose and other early Christian poets, short and long syllables alternating four times for a total of eight. (Substitutions are very common, especially since vowel quantities were already weakened in the 5th century, and hardly perceived as such in the High Middle Ages.) As such, it could in theory be sung in any one of a great many melodies, and other common hymns in this meter were often sung with different music from one church to another. However, it was an essential characteristic of the medieval Cistercians to keep a strict uniformity of observance in all their houses, and it is almost certain that they would have all used the same music.

The words of the third stanza “By the figure of a dog with a red back” refer to an episode recorded in the life of St Bernard. When his mother Aleth was pregnant with him (the third of her seven children, of whom four others are Blesseds), she dreamt that she was carrying a barking white dog with some red hair on its back. A religious man whom she consulted explained this dream to mean that the child she bore would be like the dogs mentioned in Psalm 67, “The tongues of your dogs lick the blood of their enemies”, guarding the house of God against its enemies, a preacher, and a healer of souls. This latter idea derives from St Gregory the Great’s symbolic interpretation of the dogs that licked the sores of Lazarus (hom. 40 in Evang.), in a passage which is read in the Roman Breviary on Thursday of the second week of Lent. “A dog’s tongue heals the sore which it licks; and so do holy teachers, when they instruct is in the confession of our sins, touch the sores of our souls by their tongues (i.e. their speech).” The following stanza refers to a vision of the Child Jesus which Bernard himself had when he was a boy, and fell asleep while waiting with his family to go out to Matins and the Midnight Mass of Christmas.

|

| Christ Embracing St Bernard, ca. 1625, by Francisco Riablta (1565-1628). Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Splendor paternae gloriae – an original hymn of St Ambrose himself, which the

Cistercians sing at Sunday Lauds, the Roman Office at Monday Lauds.

Jesu, nostra redemptio – from the feast of the Ascension, pre-Urban VIII

Conditor alme siderum – from Vespers of Advent, pre-Urban VIII

O lux, beata Trinitas – Saturday Vespers, pre-Urban VIII

Deus, creator omnium – the Ambrosian hymn for Sunday Vespers

Summi largitor praemii – a hymn for Lent sung by the Cistercians at Matins;

also used at Sarum, but not in the Roman Office.

Magnum salutis gaudium – processional hymn for Palm Sunday

Aeterna Christi munera – Matins hymn of the Apostles.

Beata nobis gaudia – Lauds hymn of Pentecost.

In addition, the first line of the second stanza, “Exsultet caelum laudibus”, is the title of the pre-Urban VIII version of the Vespers hymn of the Apostles. (Like all the religious orders that retained their own Uses of the Divine Office, the Cistercians never adopted Pope Urban VIII’s reform of the hymns.)

The difficulty of this trick is to integrate the titles into the words of a new composition in a new sense. Some of the expressions in the vocative case, such as “Jesu, nostra redemptio,” could be interchanged with any of the others, (I do not say this as a critique of the author; medievals valued originality far less than we do,) but the last three are particularly well chosen.

The Cistercians were founded at the very end of the 11th century as “strict constructionalists” of the original Rule of St Benedict, which they felt had been unhappily compromised by later developments and customs that emerged within the Cluniac monastic empire. The term which St Benedict uses for “hymn” in the Rule (capp. 9, 12, 13 and 17) is “ambrosianum”, since it was St Ambrose who first introduced the use of hymns into the West. This led the Cistercians to the believe that St Benedict’s original intention was not merely that monks should sing “a hymn” at certain Hours, but that they should use the specific corpus of hymns used by Ambrose himself. This corpus would be found, as they thought, in the Ambrosian Divine Office; they therefore sent people to Milan to copy out the Ambrosian hymnal then in use, and bring it back to Citeaux. It was incorporated into their Office to the despite of many hymns which at that point had long been in general use within the broad liturgical family of the Roman Rite. This was very controversial, even for an age in which there was a great deal of liturgical variation, and the Order was eventually pressured into adopting the traditional corpus of hymns, with some variations. This is why some of the original Ambrosian hymns such as “Splendor paternae gloriae” are given a more prominent place within the Cistercian Office than they were elsewhere.

Posted Thursday, August 20, 2020

Labels: Ambrosian Rite, Cistercians, hymns, Liturgical History, Medieval Liturgy

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Music for First Vespers of the Assumption

Gregory DiPippo| O quam glorifica luce coruscas, Stirpis Davidicae regia proles! Sublimis residens, Virgo Maria, Supra caeligenas aetheris omnes. |

O with how glorious light thou shinest, royal offspring of David’s race! dwelling on high, O Virgin Mary, Above all the regions of heaven. |

| Tu cum virgineo mater honore, Caelorum Domino pectoris aulam Sacris visceribus casta parasti; Natus hinc Deus est corpore Christus. |

Thou, chaste mother with virginal honor, prepared in thy holy womb a dwelling place for the Lord of heaven; hence God, Christ, was born in a body. |

| Quem cunctus venerans orbis adorat, Cui nunc rite genuflectitur omne; A quo te, petimus, subveniente, Abjectis tenebris, gaudia lucis. |

Whom all the word adores in veneration, before whom every knee rightfully bends, From whom we ask, as thou comest to help, the joys of light, and the casting away of darkness. |

| Hoc largire Pater luminis omnis, Natum per proprium, Flamine sacro, Qui tecum nitida vivit in aethra Regnans, ac moderans saecula cuncta. Amen. |

Grant this, Father of all light, Through thine own Son, by the Holy Spirit, who with liveth in the bright heaven, ruling and governing all the ages. Amen. |

The Sarum and Dominican Uses also have a special Magnificat antiphon for First Vespers of the Assumption, much longer than those typically found in the Roman Use.

Aña Ascendit Christus super caelos, et praeparavit suae castissimae Matri immortalitatis locum: et haec est illa praeclara festivitas, omnium Sanctorum festivitatibus incomparabilis, in qua gloriosa et felix, mirantibus caelestis curiae ordinibus, ad aethereum pervenit thalamum: quo pia sui memorum immemor nequaquam exsistat. – Christ ascended above the heavens, and prepared for His most chaste Mother the place of immortality; and this is the splendid festivity, beyond comparison with the feasts of all the Saints, in which She in glory and rejoicing, as the orders of the heavely courts beheld in wonder, came to the heavenly bridal chamber; that She in her benevolence may ever be mindful of those that remember her.

Wednesday, March 21, 2018

The Feast of St Benedict 2018

Gregory DiPippo |

Saints Benedict and Bernard, by Diogo de Contreiras, 1542; painted for the Cistercian convent of Santa Maria de Almoster in Portugal. (Public domain image from Wikimedia.)

|

|

| The first two pages of the Rule of St Benedict, with the Prologue to be read on March 21st, from a Cistercian Martyrology printed at Paris in 1689. |

Posted Wednesday, March 21, 2018

Labels: Benedictines, Cistercians, feasts, Rule of St. Benedict, St. Benedict

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Leaves from an 18th-Century Cistercian Gradual

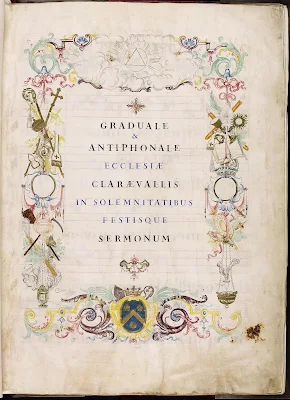

Gregory DiPippo |

| “Gradual and Antiphonal of the church of Clairvaux, on solemnities and feasts of sermons.” In point of fact, this particular book only includes a small number of major feasts. - Since the Cistercians, with characteristic simplicity, never doubled any of the antiphons in the Divine Office, the traditional Roman terminology for the grades of feasts, “double, semidouble, simple,” was not very useful to them. The highest grade of feast was therefore called “sermonis - of a sermon”, to indicate that a sermon was supposed to be delivered to the community on that day. The other grades were called “two (publicly sung) Masses”, “twelve readings (at Matins)”, “three readings” and “commemoration.” |

|

| Decorative page before Christmas |

|

| Decorative page before the Annunciation |

|

| The first antiphon of Vespers on Christmas Eve |