The lecture is available live via Zoom. An RSVP is required, and space is limited. The lecture is available for free, but if your means allow we are grateful for a donation to support the work of the Catholic Institute of Sacred Music.

Thursday, April 03, 2025

Tenebrae: The Church’s “Office of the Dead” for Christ Crucified

Jennifer Donelson-NowickaThe lecture is available live via Zoom. An RSVP is required, and space is limited. The lecture is available for free, but if your means allow we are grateful for a donation to support the work of the Catholic Institute of Sacred Music.

Saturday, April 13, 2024

Tenebrae 2024 Photopost (Part 2)

Gregory DiPippoThis post concludes the Tenebrae part of our Holy Week photopost series; we will move on to the other ceremonies of the Triduum next week. Many thanks to all the contributors - feliciter!

Friday, April 12, 2024

Tenebrae 2024 Photopost (Part 1)

Gregory DiPippoMarching on into the Triduum, here is the first set of photos of Tenebrae services. As always, there is always room and time for more, so please feel free to send yours in to photopost@newliturgicalmovement.org, and don’t forget to include the name and location of the church; and of course, our thanks to all the contributors - feliciter!

Monday, February 12, 2024

Three Major Publications for the Pre-55 Holy Week

Peter KwasniewskiWith that as a prefatory remark, here are three new publications for the pre-55 Holy Week, which continues its quiet conquest.

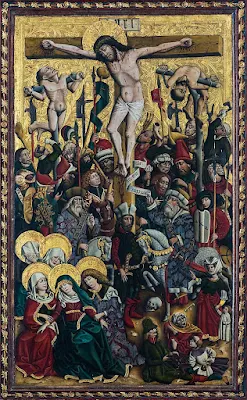

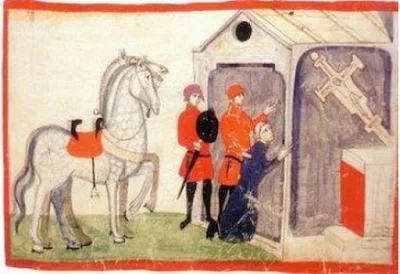

I am pleased to announce the release of The Masses of Holy Week & Tenebrae, published by Os Justi Press in time for Lent. This book contains the complete pre-55 Latin texts, with English translation, for Palm Sunday, the Triduum Masses, and the Office of Tenebrae, including complete Gregorian chants. Simple rubrics are indicated. No page turning is required. The book features many medieval illustrations as well. In the PDF they are in color; in the printed book, in grayscale.

Ideal for scholas, for personal study, or as a congregational worship aid, the book is handsomely printed with readable type and weighs in at nearly 500 pages. The cost is $20. Bulk discounts are available (and for multiple countries, not just the USA) by contacting the publisher. The book is also available through Amazon, including all of its international sites.

The cover is shown above. Below are some sample pages; more may be found here.

Wednesday, March 29, 2023

Tenebrae with Tallis’ Lamentation in Louisville, Kentucky, April 5th

Gregory DiPippoOn Wednesday, April 5th, beginning at 8:00 pm, St Martin of Tours Catholic Church and Our Lady and St John Catholic Church will host a Tenebrae service at the parish of St Martin, located in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, at 639 South Shelby Street. The music, sung by the choir of St Martin of Tours, will include Thomas Tallis’ setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah and the motet Christus Factus Est by Anton Bruckner.

Monday, April 25, 2022

Experiences That Make One a Traditionalist

Peter KwasniewskiMy books mention many such experiences, but here are two that are especially appropriate to share in Easter week.

The first was the contrast I noticed, several years in a row, between the modern (Paul VI) Easter Vigil and the Easter Sunday Missa Cantata of the Roman Rite. The reason for comparing these two is that I was involved at the time in providing music for both — the “Ordinary Form” on Saturday night and the “Extraordinary Form” (how quaint are those terms now!) on Sunday morning.

The Paul VI vigil had no “spaces,” no obvious opening to mystery through which one could enter. It was a flood of didactic text, spoken aloud, with musical interludes. Modern people are already awash in words. Do we really need more? In the N.O. Easter Vigil, one felt that one had been thoroughly drenched in the Bible readings conducted in Nabbish, a lengthy homily, the unsatisfying glamor of receiving some people into the church in a ritual that culminated in applause, and a celebration of the Eucharist wholly lacking in supernatural resonance or fearful majesty. It made an impression for sheer length, number of lilies, and candles, but otherwise it was like cookie dough — the same consistency throughout.

The Easter Missa cantata, on the other hand, was full of the sound of Alleluias sung in Gregorian chant — sixteen of them (not counting the repetitions of the Communion antiphon). The chants for Easter are strong, sometimes strange, always unearthly, already half-dwelling in the realm of eternity. The church, ablaze with white and gold… the ritual nailed to the altar, from which salvation pours out like blood and water… the clouds of incense billowing… all point to the mysterious reality of the Crucified and Risen One — and this is something that can be perceived by anyone seeking God or even seeking some meaning in life. Marshall McLuhan said, decades ago, that modern culture is obsessed with images and that the Church must therefore provide images of great power: visual and audible images that are startlingly different from what secular culture offers. At the Easter morning sung Mass, I had an almost unnerving sense of stepping back through time across all the centuries that separated me from the resurrection of Christ and coming once again into His powerful presence. This was a ritual that somehow poured from His glorified wounds to bathe me in their light. There was a holy awe about the place, a restrained joy coiled like a spring ready to leap to heaven, a hushed adoration like that of Mary Magdalene when she discovered Christ in the garden and He would not let her touch Him.

Let me not be misunderstood: I am not calling into question the good will of anyone who contributed to the Easter Vigil. On the contrary, there was abundant good will, which I remember fondly. The problem is deeper than the individuals: it is in the rites they are using and the customs that have grown up around them to the point of having nearly the force of law. The face liturgy presents to us depends much more on the rites and customs than it does on the personnel who happen to be using them; the former determine and delimit the possible range of influence for the latter.

The second experience was singing, and then reflecting on, Lesson III of Holy Saturday’s Tenebrae: “Incipit Oratio Jeremiae Prophetae.”

Remember, O Lord, what is come upon us:

consider and behold our reproach.

Our inheritance is turned unto aliens:

our houses to strangers.

We are become orphans without a father,

our mothers are as widows.

Our water we have drunk for money:

we have bought our wood for a price.

We were dragged by our necks,

we were weary and rest was not given unto us.

Unto Egypt, and unto the Assyrians have we given our hand,

that we might be satisfied with bread.

Our fathers have sinned, and are no more:

and we have borne their iniquities.

Servants have ruled over us:

there was none to redeem us out of their hand.

Our bread we fetched at the peril of our lives,

because of the sword in the desert.

Our skin was burnt as an oven,

by reason of the violence of the famine.

They have oppressed the women in Sion,

and the virgins in the cities of Juda.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem,

be converted unto the Lord thy God.

Pondering these prophetic words led me to see their application to our current liturgical situation, and the parallels have only grown clearer with time. We are alienated from our inheritance; our houses of worship are sold off to Masonic lodges or Hindu ashrams; we are become like orphans without a father in Rome or, in some cases, a father in our diocese; we bought our reforms for a steep price, and were dragged along without our consent; we grew weary of hyperactive participation and longed for a contemplative rest that was denied us; we exchanged our birthright for a seat at the United Nations and the European Union; those who fomented our disasters are mostly long-gone and we suffer from their sins; slaves of fashion rule over the sons of God; we fetched our traditional bread wherever we could find it, afraid of the sword of church authority in the desert of the post-Council; the spiritual famine has been violent, and it has extended even to threatening the religious life of consecrated virgins. Jerusalem, O Church on earth: be converted unto the Lord thy God!

Someone once said of the liturgical reformers: “They took the faith out of our hands and knees.” The reform stripped away, or allowed to be stripped away, bodily spiritual formation. Catholics can get a visceral sense of the contrast when they attend their first Tridentine Mass and find that there’s a lot more kneeling than they are accustomed to (even at High Mass) and more demands placed on their attention in general. It is a liturgy that pre-dates the invention of television, so it expects a long attention span, and the ability to be quiet and sit still. The faith has to penetrate into our bones and muscles or it remains cerebral and ineffectual.

Nowhere is this more clear than in the contrasting practices of Holy Communion. In too many churches, the faithful walk up in multiple lines and receive the Body of Christ in their hands, like people queueing for bus tickets, after which they take a cup to wash it down, like teammates sharing Gatorade. In traditional communities, the faithful kneel along the communion rail and wait until the priest comes to them to bless them with the Host — “Corpus Domini nostri + Jesu Christi custodiat animam tuam in vitam aeternam, Amen” — and places it gently on their tongues. These two contrasting scenes are, in reality, expressive of two different ideas of religion, if we take religion in the sense of the virtue by which we offer God our worship through concrete words and actions.

This is why I am not surprised that the former Benedictine monk Gabriel Bunge, a world expert on the Trinity icon of Rublev, left the Catholic Church to become Eastern Orthodox. No one ever introduced him to the real Western tradition that corresponded to what he was studying from the East. He came to the conclusion that the only authentic tradition left was the East. His conclusion should rather have been that the modern West had abandoned its own authentic tradition, and that we have an urgent calling to recover it.

After experiences like the two I recounted, one’s soul is seared with the truth, at once liberating and daunting: I cannot go back to the 60s and 70s, to those pathetic works of human hands. Let the dead bury the dead. It is the perennially youthful Roman Rite that gives joy to me, that shines forth light and truth.

Posted Monday, April 25, 2022

Labels: Easter, Easter Vigil, Gregorian Chant, McLuhan, Peter Kwasniewski, Tenebrae, verbosity

Friday, April 15, 2022

The Good Things of Good Friday

Michael P. FoleyWithout doubt the most dolorous day of the Church’s annually recurring sanctification of time is Good Friday, the day on which she commemorates in a special manner the Passion and Death of Our Lord, the day that is the culmination of forty days of fasting and penance, and the only day of the year in the Latin rites of the Church on which her altars are deprived of the Holy Sacrifice.

But as Christian disciples who are sorrowful but always rejoicing (see 2 Cor. 6, 10), Good Friday is not an occasion of defeat but of love's triumph. Today, let us look at five good effects of this solemn, somber day.Tuesday, April 13, 2021

Tenebrae 2021 Photo & Audiopost (Part 2)

Gregory DiPippoFriday, April 09, 2021

Tenebrae 2021 Photopost (Part 1)

Gregory DiPippoOne of the many enouraging signs of the slow-but-steady growth of interest in the recovery of our Catholic liturgical tradition is the increasing number of churches that do Tenebrae services during the Sacred Triduum. In 2015, the year I took over as managing editor of NLM, and in the three years after that, we had only one photopost for Tenebrae; in 2019, we got up to two, and after last year's interruption, we will have two again this year. There is always room for more, so feel free to send in photos of any part of the Triduum or Easter to photopost@newliturgicalmovement.org, remembering to include the name and location of the church.

Saturday, April 03, 2021

The “Kyrie puerorum”: An Ancient Tenebrae Tradition

Gregory DiPippoOur thanks to Mr Jehan-Sosthènes Boutte for sharing with us this artice about a particularly interesting medieval variant found in the Tenebrae Offices of various Uses.

Then the strepitus begins--the noise that symbolizes the earthquake that took place at Christ's death, which is made by banging books on the choir stalls. While this symbolism maintains, it is also as if, with the strepitus, we’re begging Christ to come out of the tomb, especially on Holy Saturday. While the strepitus is still going on, the Christ candle--the Light which the darkness cannot overcome--is brought back out and replaced in the hearse, and all depart in silence.

When the Roman Office was simplified due to the exile of the Papacy in Avignon, the singing of the Gradual Christus factus est replaced a very curious and old litany – present in the Antiphonary of Compiègne – in which that same text, Christus factus est, was sung, in between several verses, on another melody. This ancient litany was kept by most French diocesan rites, particularly that of Paris.

Dómine, miserére.

Christus Dóminus factus est oboediens usque ad mortem.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ the Lord became obedient unto death.

℣. Qui expansis in cruce mánibus, traxisti omnia ad te sáecula. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Qui prophétice prompsisti: Ero mors tua, o mors. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Thou who with hands outstretched upon the cross didst draw all ages unto Thyself. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Thou who prophetically foretold: I shall be thy death, o death. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Vita in ligno móritur: infernus et mors lugens spoliátur. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Te qui vincíri voluisti, nosque a mortis vínculis eripuisti. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Life upon the Tree did die: hell and death in anguish are despoiled. ℟. Christe eleison.

℣. Thyself wert willing to be bound, and so didst redeem us from the bonds of death. ℟. Christe eleison.

Christus Dóminus factus est oboediens usque ad mortem, mortem autem crucis.

Kyrie eleison. Kyrie eleison. Kyrie eleison.

Dómine, miserére.

Christus Dóminus factus est oboediens usque ad mortem.

Mortem autem crucis.

Christ the Lord became obedient unto death, even the death of the Cross.

Kyrie eleison. Kyrie eleison. Kyrie eleison.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ the Lord became obedient unto death.

Even the death of the Cross.

Thursday, April 01, 2021

Photopost Request: The Sacred Triduum and Easter

Gregory DiPippoPlease read this! – I would ask people to do a few things to make it easier for us to process the photos. The first is to size them down so that the smaller dimension is around 1500 pixels. The second is to send the pictures as zipped files, which are a lot easier to process, (not links, and not as photos attached to an email). The third is to not mix photos of one ceremony with those of another, and to put the name of the ceremony (“Tenebrae”, “Holy Thursday”, “Good Friday”, “Holy Saturday”, and “Easter Sunday”) as the subject of the email. Your help is very much appreciated.

Here are just a few highlights from 2019, starting with the altar of repose at the cathedral of St Paul in Birmingham, Alabama.

Posted Thursday, April 01, 2021

Labels: Good Friday, Holy Saturday, Holy Thursday, Photopost, Tenebrae

Thursday, March 25, 2021

A Tenebrae Service with the St John Choir Schola on Spy Wednesday

Gregory DiPippoFriday, April 10, 2020

Good Friday 2020

Gregory DiPippo |

Bartolomé Estebán Murillo, ca. 1675; Public domain image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City

|