The Christian connection between culture, conservative values, the common good and the natural law

In my post one week ago (entitled What is Culture), I described how a beautiful culture emerges through the loving interaction between the people in a society and their love of God. Now, love is by nature freely given (the moment we are compelled to love, it is no longer love!). Therefore, freedom - the freedom to love God and neighbor - is a necessary condition for a beautiful culture.

What is freedom? Many feel that freedom is simply the absence of constraint and compulsion. That is part of it, but the traditional approach has a deeper understanding. We can define freedom in the traditional understanding as the capacity to choose the practicable best. For us to be in full possession of freedom and be able to choose the course that is best, therefore, three components must be present.

The first component is the absence of constraint or compulsion; the second is a full knowledge of what is best for us; and the third is the power to act in accordance with what is best. The good that is best for each of us in the context of a society is known as the ‘common good’. When we act in accordance with the common good, then we also do what is best for ourselves. In the proper order of things, the personal good and the common good are never in conflict with each other. The most obvious guides to seeking the common good are the moral law and the principles of justice as prescribed by Christ’s Church. All authentic and beautiful Christian cultures emerge from the freely taken actions of the members of a society toward the common good.

It is in the interest of a Christian society therefore, to promote freedom by a system of laws that are just, and so give security to the individual to act in accordance with the freedom to be moral and good. Such a system of laws would be directed to restraining people from interfering with the freedom of others. The state also encourages the formation of people through an education that will help them to know the common good. The state fulfils its role by enabling good teachers, and most especially parents as teachers of the children, to teach well. If these conditions are satisfied then I believe a culture of beauty will emerge organically from the bottom up.

Analogously, and in regard to supporting the arts themselves, I believe that it is better to strive to create the conditions that promote the freedom to pursue art as a career, than to try to impose the elitist vision of what art ought to look like onto people from the top down. The freedom given to an artist in this context is understood as consisting of a knowledge of what sort of art might benefit society, and the skill and means to create it. A top down imposition of artistic standards almost always tends to restrict freedom, and so undermines the chance of creating an authentically beautiful culture.

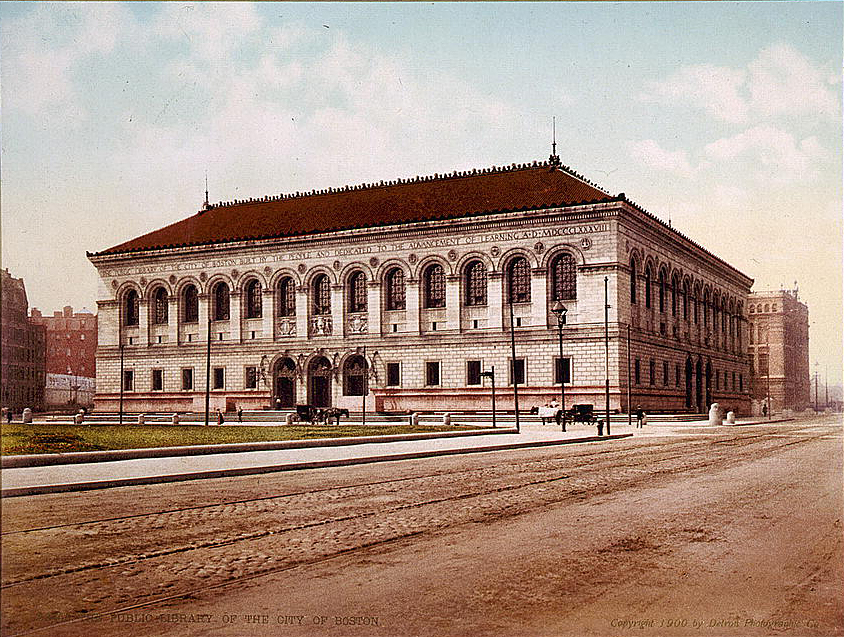

One might think that an exception to this rule would be those arts that are to be used directly by government, for example the design of civic buildings, for which government must, by necessity, be involved. However, even then the government ought to be mindful that it serves the people and does not direct them, and hence be aware both of tradition (the people of the past) and what most people want. Also, because architecture and public spaces have an impact on the whole community and not just those who occupy them, then the community that it will impact most immediately must have a say on the style of buildings. The authority that specifies such buildings must reflect the principle of subsidiarity as far as possible. A state Capitol building should reflect what the people of the state want and used to want, i.e. tradition, while the small city government would select the architecture for the town hall, reflecting what the neighborhood wants.

For example, the Hungarian government recently undertook a building program to replace the brutalist style of buildings built by communists in its capital Budapest with more elegant architecture. In the last 10 years, it has rebuilt or renovated in the style that is in accord with the traditional architecture of the city, and this has been a highly popular program. Furthermore, the level of tourism in the city has increased dramatically, with the new buildings being the attractions as much as the old.

Returning to our focus on the role of the state and its connection to culture: the pattern of positive law (those laws created by human government) of a society will inevitably be different from one nation to another, even for those nations that are seeking to create laws for all the right reasons. The truths of the natural law which inform positive law are eternal and universal principles; but this universality of the principles themselves does not mean that human society immediately and instantaneously comes to know and apply these principles universally, in all places, in exactly the same way. Human knowledge, like human society, must progress slowly, in stages, step-by-step, and organically, or else it is not a true “human society” at all. It does so through a process of trial and error, gradually seeing what works best. Therefore each society will take a different path towards this knowledge.

The good Christian society recognizes the difficulty of knowing fully, and applying well, the universal principles of the natural law, and thus the good Christian society seeks the aid of revelation, Tradition, and the experience of past laws to help guide reason. God revealed truths for two reasons, St Thomas Aquinas tells us, first because some truths are beyond the grasp of reason (for example, the Trinity, the Incarnation, the resurrection of the body); and second, God also revealed moral truths that, although part of the natural law and accessible to natural reason, would “only be discovered by a few, and that after a long time, and with the admixture of errors.” (ST Ia Q1,1 co.) Arising from this there are two important reasons why the pattern of the exercise of freedom will be different from one Christian nation to another. First, principles that are understood well can still be applied in different ways by different societies without contravening those principles; and second, the knowledge or understanding of a principle is very likely not perfect or full and will vary from nation to nation, each thinking that it knows best.

Accordingly, different Christian nations are free to observe the experience of other nations, imitate what is best in them, and adopt what is beautiful and good from them. This way, in the proper order of things, each nation is part of a family of distinct and autonomous nations, each helping each other to find what is best.

As mentioned in my earlier post, a culture is a sign of the core values of the society that produces it and as such it is beautiful to the degree that it is Christian. This is true even in those societies or countries that would not think of themselves as Christian. An Islamic nation, for example, has a beautiful culture to the degree that its culture is consistent with an expression of the Christian truths, even when those truths are communicated to them by the Koran.

Further, it is the Christian characteristics of different cultures that connect them to each other; and it is the different national expressions of that Christian faith manifested in characteristic patterns of loving interaction and free behaviour that distinguish different Christian cultures from each other.

So for example, historically, the United States began as a nation that adopted and then adapted a system of law from the English constitutional tradition. The English constitutional tradition is a system of laws, rooted in Christian values, yet expressed in a characteristically English way that is quite different from, for example, that of its neighbor France. In time the American system of law developed its own national characteristics, while still owing much to its English beginnings, but now expressing it in a characteristically American way. If American culture is to be transformed into one of beauty it will be one that asserts the importance of America as a distinct nation with characteristic values that are simultaneously Christian and of a particular American-English expression. As such one would expect to see similarities to English culture in American culture. It is no accident for example, that in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century, American churches and universities were modeled on the English neo-gothic style. They even hired English architects to build them, but quickly an American character emerged from these, and so while we can see the similarities between Princeton and Oxford universities, one reflects America while the other reflects England. All this was before the decline of culture in both America and England, which took hold strongly after the Second World War, and by which both nations lost a sense of the importance of the Christian faith to the defining principles of their nations, and the principles of common law that underlay each.

The task of transforming the culture in our country, America, then, is clearly one of evangelization. We hope for and work towards a society in which the culture’s ordering principle is the transfigured Christ. And people must be aware again of what that looks like in America. This latter aspect requires more than an understanding of the principles of the American constitution. It requires an appreciation also of the cultural mileau from which it emerged and a love for it.