|

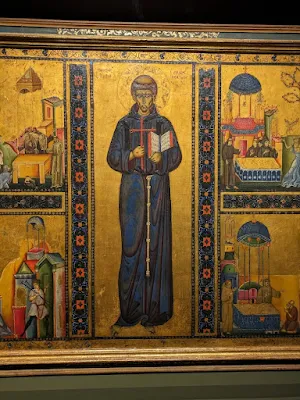

| St Francis Receives the Stigmata, by Giotto, 1295-1300; originally painted for the church of St Francis in Pisa, now in the Louvre. The predella panels show the vision of Pope Innocent III, who in a dream beheld St Francis holding up the collapsing Lateran Basilica, followed by the approval of the Franciscan Rule, and St Francis preaching to the birds. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.) |

Before the Tridentine reform, the Franciscans repeated the introit of the Exaltation, Nos autem gloriari oportet, at the Mass of the Stigmata, emphasizing not only the merely historical connection between the two events, but also the uniqueness of their founder, whom St Bonaventure describes as one “marked with a privilege not granted to any age before his own.” The modern Missal cites this introit to Galatians, 6, 14, but it is really an ecclesiastical composition, and hardly even a paraphrase of any verse of Scripture. It is also the introit of Holy Thursday, and in the post-Tridentine period, this use was apparently felt to be a little hubristic; it was therefore replaced with a new one, Mihi autem, which quotes that same verse exactly. “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ; by whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world.”

The verse with which it is sung is the first of Psalm 141, “I cried to the Lord with my voice: with my voice I made supplication to the Lord,” the Psalm which St Francis was in the midst of reciting at the moment of his death. The music of this later introit is copied almost identically from another which also begins with the words Mihi autem, and is sung on the feasts of various Apostles, underscoring the point that St Francis was, as one of the antiphons of his proper Office says, a “vir catholicus et totus apostolicus – a Catholic man, wholly like the Apostles.”

St Robert had a great devotion to St Francis, on whose feast day he was born in 1542. His native city, Montepulciano, is in the southeastern part of Tuscany, fairly close to both Assisi and Bagnoreggio, the home of St Bonaventure, and very much in the original Franciscan heartland. Not long after he entered the Jesuits, the master general, St Francis Borgia, commissioned a new chapel dedicated to his name-saint, with a painting of him receiving the Stigmata as the main altarpiece. It was built within what was then the Order’s only church in Rome, dedicated to the Holy Name of Jesus, devotion to which was a Franciscan creation, and heavily promoted by another of their Saints, Bernardin of Siena, who was also Tuscan. This chapel was clearly intended to underline the similarities between the Jesuits and Franciscans as orders promoting reform within the Church, while remaining wholly obedient to it, zealous evangelizers, strictly orthodox, and spiritually grounded in an intensely personal devotion to and union with Christ.

|

| The chapel of the Sacred Heart, originally dedicated to St Francis of Assisi, at the Jesuit church of the Holy Name of Jesus in Rome, popularly known as ‘il Gesù.’ In 1920, the original altarpiece of St Francis Receiving the Stigmata by Durante Alberti was replaced by the painting of the Sacred Heart seen here, a work of Pompeo Battoni done in oil on slate in 1767. Previously displayed on the altar of St Francis Xavier, which is right outside this chapel, it was the very first image of the Sacred Heart to be exposed for veneration in Italy after the visions of St Margaret Mary Alacoque. The other images of St Francis, all part of the chapel’s original decoration, remain in place. (Photo courtesy of Mr Jacob Stein, author of the blog Passio Xpi.) |

St Francis is today held in admiration so broadly by Catholics, non-Catholics and even non-Christians alike, that it is perhaps hard for us to appreciate today how he was seen by the original Protestant reformers. Even within Luther’s lifetime, it was hardly possible to get two of them together to agree on any point; broadly speaking, however, they generally accepted that things had really gone wrong in the Church with the coming of the mendicants, especially the Franciscans, and the flourishing of their teachings in the universities. Luther himself once said “If I had all the Franciscan friars in one house, I would set fire to it”, and more generally, “a friar is evil every way, whether in the monastery or out of it.” Most Protestants had no patience for the ascetic ideals embodied by Saints like Francis and the other mendicants, an attitude sadly shared by supercilious humanists within the Church like Erasmus.

Of course, the mendicants were not immune to the widespread decadence of religious and clerical life justly decried by the true reformers of that age, and which sadly provided much grist for the Protestant mill. And yet, while Ignatius of Loyola was still the equivalent of a freshman in college, the great Franciscan reform of the Capuchins had already begun; where the Jesuits would soon prove the most effective of the new orders in combatting the heresies of the 16th century, the Capuchins would take that role among the older ones. This may be what moved Luther to say, “If the emperor would merit immortal praise, he would utterly root out the order of the Capuchins, and, for an everlasting remembrance of their abominations, cause their books to remain in safe custody. ’Tis the worst and most poisonous sect; the (other orders of) friars are in no way comparable with these confounded lice.” [3]

|

| Fra Matteo Bassi, founder of the Capuchins, and quite possibly the only founder of a Franciscan order who was never canonized; 17th century, author unknown. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.) |

St Francis was both a product of the Middle Ages, and a creator of one of its most important and characteristic institutions; he was no more a creation of Luther and Calvin’s imaginary “primitive” church than he was a modern environmentalist. The placement of his feast on the general calendar serves as a very useful reminder that it was a man of that era who was the first conformed to Christ so entirely that he merited to bear His wounds upon his own body.

On April 16, 1959, Pope St John XXIII addressed the following words to a gathering of Franciscans in the Lateran Basilica, where Pope Innocent III had once met the Poor Man of Assisi himself, the occasion being the 750th anniversary of the approval of the Franciscan Rule. “Beloved sons! Permit us to add a special word from the heart, to all those present who belong to the peaceable army of the Lay Tertiaries of St Francis. ‘Ego sum Ioseph, frater vester.’ (‘I am Joseph, your brother’, citing Genesis 45, 4, Joseph being his middle name), … This we ourselves have been since our youth, when, having just turned fourteen, on March 1, 1896, we were regularly inscribed through the ministry of Canon Luigi Isacchi, our spiritual father, who was then the director of the seminary of Bergamo.” He went on to recall the Franciscan house of Baccanello, near the place where he grew up, as the first religious house he ever knew, and that four days earlier, he had canonized his first Saint, the Franciscan Carlo of Sezze.

The following year, Pope John approved the decree for the reform of the Breviary and Missal which reduced the feast of St Francis’ Stigmata to a commemoration. As such, the Mass can still be celebrated ad libitum, but is no longer mandatory, and the story of the Stigmata is no longer told in the Breviary. In the post-Conciliar reform, it was removed from the general calendar entirely, and replaced by the feast of St Robert Bellarmine, who died in 1621 on the very feast day he had promoted. It is still kept by the Franciscan Orders.

[1] Before the Tridentine reform, there were many feasts and Saints who were celebrated everywhere the Roman Rite was used, and many of these feasts did originate in Rome itself, but there was no such thing as a “general” calendar of feasts that had to be kept ubique et ab omnibus. When the first general calendar was created in 1568, which is to say, a calendar created with the specific intention that it would also be used outside its diocese of origin, a number of miracle feasts were included; all of these were present in pre-Tridentine editions of the Roman liturgical books, and celebrated in many other places as well.

[2] The feast was added to the calendar by Pope Paul V as a semidouble ad libitum in 1615, made mandatory by Pope Clement IX (1667-69), and raised to the rank of double by Clement XIV, the last Franciscan Pope.

[3] Thanks to Dr Donald Prudlo for this quote from Luther, and the one that precedes it.

.jpg)