Wednesday, September 10, 2025

Laus Beatae Mariae Virginis

Gregory DiPippoThursday, August 14, 2025

Music for First Vespers of the Assumption

Gregory DiPippo| O quam glorifica luce coruscas, Stirpis Davidicae regia proles! Sublimis residens, Virgo Maria, Supra caeligenas aetheris omnes. |

O with how glorious light thou shinest, royal offspring of David’s race! dwelling on high, O Virgin Mary, Above all the regions of heaven. |

| Tu cum virgineo mater honore, Caelorum Domino pectoris aulam Sacris visceribus casta parasti; Natus hinc Deus est corpore Christus. |

Thou, chaste mother with virginal honor, prepared in thy holy womb a dwelling place for the Lord of heaven; hence God, Christ, was born in a body. |

| Quem cunctus venerans orbis adorat, Cui nunc rite genuflectitur omne; A quo te, petimus, subveniente, Abjectis tenebris, gaudia lucis. |

Whom all the word adores in veneration, before whom every knee rightfully bends, From whom we ask, as thou comest to help, the joys of light, and the casting away of darkness. |

| Hoc largire Pater luminis omnis, Natum per proprium, Flamine sacro, Qui tecum nitida vivit in aethra Regnans, ac moderans saecula cuncta. Amen. |

Grant this, Father of all light, Through thine own Son, by the Holy Spirit, who with liveth in the bright heaven, ruling and governing all the ages. Amen. |

The Sarum and Dominican Uses also have a special Magnificat antiphon for First Vespers of the Assumption, much longer than those typically found in the Roman Use.

Aña Ascendit Christus super caelos, et praeparavit suae castissimae Matri immortalitatis locum: et haec est illa praeclara festivitas, omnium Sanctorum festivitatibus incomparabilis, in qua gloriosa et felix, mirantibus caelestis curiae ordinibus, ad aethereum pervenit thalamum: quo pia sui memorum immemor nequaquam exsistat. – Christ ascended above the heavens, and prepared for His most chaste Mother the place of immortality; and this is the splendid festivity, beyond comparison with the feasts of all the Saints, in which She in glory and rejoicing, as the orders of the heavely courts beheld in wonder, came to the heavenly bridal chamber; that She in her benevolence may ever be mindful of those that remember her.

Monday, July 07, 2025

The Translation of St Thomas Becket

Gregory DiPippoBecause Thomas had given his life to defend the independence of the Church from undue interference by the civil power, King Henry VIII had the shrine destroyed in 1538, and forbade all devotion to him, even requiring that every church and chapel named for him be rededicated to the Apostle Thomas. The place within Canterbury Cathedral where the shrine formerly stood has been empty ever since; this video offers us a very nice digital recreation. Like the nearly contemporary shrine of St Peter Martyr and several others, the casket with the relics rests on top of an open arched structure, so that pilgrims can reach up and touch or kiss it from beneath, without damaging the metal reliquary itself.

Monday, June 16, 2025

Medieval Allegories of the Divine Office

Gregory DiPippoThe system of Scriptural readings assigned to the Office goes back to the 6th century; it originated in the ancient Roman basilicas, but we know nothing about how it was devised. When it was extensively revised in the Tridentine reform, the basic pattern of readings (Isaiah in Advent, St Paul after Epiphany, Genesis in Septuagesima etc.) was not changed, but completed and expanded. Following the feast of Pentecost, the readings are from the books of Kings until the first Sunday of August, when the Church takes up the Sapiential books, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus. In September are read Job, Tobias, Judith and Esther, followed by the two books of the Maccabees in October, and Ezechiel, Daniel and the twelve minor prophets in November.

As he goes through the liturgical texts of the individual Sundays after Pentecost, Durandus is particularly concerned to explain both the mystical significance of the readings taken from a particular book, and their connection with the Sunday Masses. Of course, the date of Pentecost changes every year, ranging from May 10th to June 13th; therefore, the Office readings, which are tied to the calendar months, coincide with a different Sunday every year. Durandus’ allegorical links between these readings and the Sundays assumes a period of only 24 weeks between Pentecost and Advent, although there can be as many as 28. This section of the Rationale is quite long, and I here give only a few selection from the more interesting passages, all from the sixth book.

And here begins the fourth time of pilgrimage, because we are on the way to return to the fatherland. But because we have enemies before we arrive there, namely, the flesh, the world and the devil, the readings are taken from the books of Kings, which treat of wars and victories, that we may have victory, as the Jews did against the Philistines, …

But because war is not waged well without discretion, in the period that follows come the books of Solomon. Again, because vices arise, against which patience is necessary, the history of Job comes after that.

(Referring then to the principal personages whose stories are told in the Books of Kings) Saul is proposed to us as an example, who by disobedience lost (the rule of) the kingdom, that we may not be disobedient as he was, and lose the eternal kingdom. But David was humble in all his works, …

|

| Saul and David, by Rembrandt, ca. 1655 |

|

| King Salomon, by Pedro Berruguete, ca. 1500 |

But in the Offertory is shown the efficacy of prayer, and the whole text is the prayer of Moses, taken from Exodus (chapter 32), when he prayed for the children of Israel, who made the golden calf for themselves, … which proves that the merits of the Saints benefit us.

|

| Heliodorus Driven from the Temple (2 Maccabees 3), by Bertholet Flémal, 1658-62, following Raphael’s depiction of the same subject in the Stanza di Elidoro in the Vatican Museums. |

Tuesday, June 03, 2025

A Sequence for the Ascension

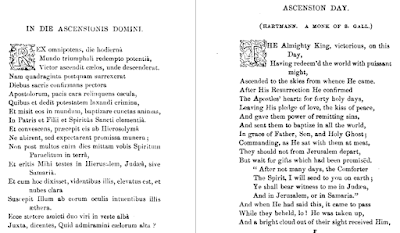

Gregory DiPippoFor the ongoing feast of the Ascension, here is a sequence for it which was sung in the Uses of Sarum, York, and Hereford in England, and in those of Paris and Sens in France. (Despite its great antiquity, and its status as the capital of France, Paris was a suffragan diocese to Sens until 1622.) It is attributed, though far from certainly, to the Blessed Hermanus Contractus (Herman the Cripple), better known as the author of the great Marian antiphons Alma Redemptoris Mater and Salve, Regina. This recording is interesting for the way it alternates between a single voice and the full choir; in fact, sequences were most typically designed to be sung in some form of alternation like this. The Latin text with English translation, taken from Sequences from the Sarum Missal, with English Translations, by Charles Buchanan Pearson (Bell and Daldy; London, 1871. Click images to enlarge.)

Wednesday, May 28, 2025

How Medieval Christians Celebrated the Rogation Days (with a Dragon)

Gregory DiPippo“Mindful of that promise of the Gospel, ‘Ask, and ye shall receive,’ (John 16, 24; from the Gospel of the Sunday which precedes the Lesser Litanies) St Mamertus, bishop of Vienne, in this week instituted the three days of the Litanies, because of an urgent necessity … days which are greatly celebrated by every church with fasts and prayers. The Greek word ‘litany’ means ‘supplication,’ because in the Litanies we beseech the Lord that he may defend us from every adversity, and sudden death; and we pray the Saints that they may intercede for us before the Lord. … The Church celebrates the Litanies with devotion in these three days, with (processional) crosses, banners, and relics She goes from church to church, humbly praying the Saints that they may intercede with God for our excesses, ‘that we may obtain by their intercession what we cannot obtain by our own merits.’ (citing a commonly used votive Collect of all the Saints.) ...

It is the custom of certain churches also to carry a dragon on the first two days before the Cross and banner, with a long, inflated tail, but on the third day, (it goes) behind the Cross and banners, with its tail down. This is the devil, who in three periods, before the Law, under the Law, and under grace, deceives us, or wishes to do so. In the first two (periods) he was, as it were, the lord of the world; therefore, he is called the Prince or God of this world, and for this reason, in the first day, he goes with his tail inflated. In the time of grace, however, he was conquered by Christ, nor dares he to reign openly, but seduces men in a hidden way; this is the reason why on the last day he follows with his tail down.” (Ordo Officiorum Ecclesiae Senensis, 222)

Oderico does not describe the dragon, but given that Siena is in Tuscany, still a major center of leather-working to this day, we may imagine that the dragon itself was a large wooden image mounted on wheels or a cart, and the inflatable tail something like a leather bellows. It should be noted that in addition to the processional cross, Oderico mentions both banners and relics as part of the processional apparatus. In the medieval period, it was considered particularly important to carry relics in procession; so much so that, for example, a rubric of the Sarum Missal prescribes that a bier with relics in it be carried even in the Palm Sunday procession. A typical bier for these processions is shown in the lower right corner of this page of the famous Book of Hours known as the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. made by the Limbourg brothers between 1411 and 1416.

Posted Wednesday, May 28, 2025

Labels: Medieval Liturgy, Medieval Piety, processions, Relics, Rogation Days

Saturday, May 03, 2025

The Gospel of Nicodemus in the Liturgy of Eastertide

Gregory DiPippo.jpg) |

| Christ and Nicodemus, by Fritz van Uhde, ca. 1886 |

In his Treatises on the Gospel of St John (11.3), St Augustine say that “this Nicodemus was from among those who had believed in (Christ’s) name, seeing the signs and wonders which He did” at the end of the previous chapter. (2, 23) “Now in this Nicodemus, let us consider why Jesus did not yet entrust Himself to them. ‘Jesus answered, and said to him: Amen, amen I say to thee, unless a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.’ (John 3, 3) Therefore, Jesus entrusts Himself to those who have been born again. … Such are all the catechumens: they already believe in the name of Christ, but Jesus does not entrust himself to them. If we shall say to the catechumen, ‘Do you believe in Christ?’ he answers, ‘I believe’, and signs himself; he already bears the Cross of Christ on his forehead.”

These words refer to the very ancient custom, still a part of the rites of Baptism to this very day, by which the catechumens were signed on their foreheads with the Cross. Augustine here follows his teacher St Ambrose, who says in his book On the mysteries, “The catechumen also believes in the Cross of the Lord Jesus, by which he is also signed: but unless he shall be baptized in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, he cannot receive forgiveness of sins, nor take in the gift of spiritual grace.” (chapter 4)

Augustine then says (11.4), “Let us ask (the catechumen), ‘Do you eat the flesh of the Son of man, and drink (His) blood?’ He does not know what we are saying, because Jesus has not entrusted Himself to him.” The fact that Nicodemus first came to Christ at night (John 3, 2) also refers to his status as a catechumen. “Those who are born from water and the Spirit (John 3, 5), what do they hear from the Apostle? ‘For you were heretofore darkness, but now light in the Lord. Walk then as children of the light.’ (Eph. 5, 8) and again, ‘Let us who are of the day be sober.’ (1 Thess. 5, 8) Those then who have been reborn, were of the night, and are of the day; they were darkness, and are light. Jesus already entrusts Himself to them, and they do not come to Jesus at night as Nicodemus did…”.

Following this interpretation, the Gospel is perfectly suited for the celebration of the Pascha annotinum, in which the catechumens commemorated the day when Christ first entrusted Himself to them in both Baptism and the Eucharist.

This point is made even more clearly by the Ambrosian rite. The Church of Milan assigns two Masses to the Easter vigil and each day of Easter week, one “of the solemnity”, and a second “for the (newly) baptized”; the latter form a final set of lessons for the catechumens who have just been received into the Church. At the Easter vigil Mass “for the baptized”, the Nicodemus Gospel is read, ending at verse 13. The first prayer of this Mass begins with a citation of it: “O God, who lay open the entrance of the heavenly kingdom to those reborn from water and the Holy Spirit, increase upon Thy servants the grace which Thou hast given; so that those who have been cleaned from all sins, may not be deprived of the promises.” The Epistle, Acts 2, 29-38, is taken from St Peter’s speech on the first Pentecost, ending with the words, “and you will receive the Holy Spirit.”

On Easter itself, the Gospel of the Mass “for the baptized” is John 7, 37-39.

On the great day of the festivity, the Lord Jesus stood and cried out, saying: If any man thirst, let him come to me, and drink. He that believeth in me, as the scripture saith, Out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water. Now this he said of the Spirit which they should receive, who believed in him: [for as yet the Spirit was not given, because Jesus was not yet glorified.]However, the words noted here in brackets are omitted at this Mass. Pentecost also has two Masses, and at its Mass “for the baptized”, this Gospel is repeated, but including the final words, further emphasizing the connection between the two great baptismal feasts.

|

The remains of the Baptistery of Saint John at the Fonts (San Giovanni alle Fonti), the paleo-Christian baptistery of Milan, discovered under the modern Duomo in 1889.

|

The choice of Gospel was certainly determined by the final words, “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert, so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him, may not perish; but may have life everlasting.” St Augustine explains, “As those who looked upon the serpent did not perish from the bites of the serpents; so those who with faith look upon the death of Christ are healed from the bites of sins. But they were healed from death to temporal life: here, however, He says “that they may have eternal life.” (Tract. in Joannem, 12, 11)

Although the Octave of Pentecost is very ancient, Rome and the Papal court never kept the first Sunday after Pentecost as part of it. (This forms another parallel with Easter, since the liturgy of Low Sunday differs in many respects from that of Easter itself.) In northern Europe, as noted above, the Octave Day was a proper octave, repeating the Mass of the feast, but with different readings: Apocalypse 4, 1-10 as the Epistle, and John 3, 1-16 as the Gospel. Both of these traditions were slowly but steadily displaced by the feast of the Trinity, first kept at Liège in the early 10th century; but there was a divergence of customs here as well. When Pope John XXII (1316-34) ordered that Holy Trinity be celebrated throughout the Western Church, he placed it on the Sunday after Pentecost, a custom which became universal after Trent. But even as late as the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Low Countries and several major dioceses in Germany still kept the older Octave Day of Pentecost, and put the feast of the Trinity on the Monday after.

Others compromised between the older custom and the new by keeping the readings from the Octave of Pentecost, but inserting them into the Mass of the Trinity; this was observed at Sarum, and by the medieval Dominicans and Premonstratensians. After the Tridentine reform, however, as part of the general tendency to Romanize liturgical books, this compromise was retained only by the Old Observance Carmelites, leaving the first part of the Nicodemus Gospel only on the Finding of the Cross for all the rest of the Roman Rite.

In 1960, the feast was suppressed from the general Calendar, and relegated to the Missal’s appendix “for some places”, causing the effective disappearance of the crucial Gospel passage from the liturgy of Eastertide. This defect been partially remedied in the Novus Ordo; the reading is broken into two pieces, assigned to the Monday and Tuesday after Low Sunday, but not to any major feast of the season.

A second (and shorter) part of this article will consider the second part of the Gospel of Nicodemus, John 3, 16-21, on Pentecost Monday, June 9th.

Thursday, May 01, 2025

A Medieval Hymn for Eastertide

Gregory DiPippo| Chorus novae Jerusalem, Novam meli dulcedinem, Promat, colens cum sobriis Paschale festum gaudiis. |

Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem! To sweet new strains attune your theme; The while we keep, from care releas’d, With sober joy our Paschal Feast: |

| Quo Christus, invictus leo Dracone surgens obruto Dum voce viva personat A morte functos excitat. |

When Christ, Who spake the Dragon’s doom, Rose, Victor-Lion, from the tomb, That while with living voice He cries, The dead of other years might rise. |

|

Quam devorarat improbus Praedam refudit tartarus; Captivitate libera Jesum sequuntur agmina. |

Engorg’d in former years, their prey Must Death and Hell restore to-day: And many a captive soul, set free, With Jesus leaves captivity. |

|

Triumphat ille splendide, Et dignus amplitudine, Soli polique patriam Unam facit rempublicam |

Right gloriously He triumphs now, Worthy to Whom should all things bow; And, joining heaven and earth again, Links in one commonweal the twain. |

| Ipsum canendo supplices, Regem precemur milites Ut in suo clarissimo Nos ordinet palatio. |

And we, as these His deeds we sing, His suppliant soldiers, pray our King, That in His Palace, bright and vast, We may keep watch and ward at last. |

|

Esto perenne mentibus Paschale, Jesu, gaudium, Et nos renatos gratiae Tuis triumphis aggrega. |

(in the recording, but not in the original text) |

|

Per saecla metae nescia Patri supremo gloria, Honorque sit cum Filio Et Spiritu Paraclito. Amen. |

Long as unending ages run, To God the Father laud be done; To God the Son our equal praise, And God the Holy Ghost, we raise. |

A literal translation of the hymn’s first two lines would read “Let the choir of the new Jerusalem bring forth the new sweetness of a song.” The word “meli – song” is the genitive singular form of the Greek word “melos” (as in “melody”); this is unusual in Latin, and the line was emended in various ways. The Premonstratensians, e.g., changed it to “nova melos dulcedine – Let the choir of the new Jerusalem bring forth a song with new sweetness.” Dom Lentini disturbed the original text less by changing it to “Hymni novam dulcedinem – the new sweetness of a hymn.”

|

| This manuscript of the mid-11th century (British Library, Cotton Vesp. d. xii; folio 74v, image cropped), is one of the two oldest with the text of this hymn. |

Esto perenne mentibus

Paschale, Jesu, gaudium,

Et nos renatos gratiae

Tuis triumphis aggrega.

Jesu, tibi sit gloria,

Qui morte victa praenites,

Cum Patre et almo Spiritu,

In sempiterna saecula.

“Be to our minds the endless joy of Easter, o Jesus, and join us, reborn of grace, to Thy triumphs. – Jesus, to Thee be glory, who shinest forth, death being conquered, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, unto eternal ages.”

It is not difficult to figure out the rationale behind this change, since it appears in other features of the reform as well. As the wise Fr Hunwicke noted two years ago, “The post-Conciliar reforms made much of Easter being 50 days long and being one single Great Day of Feast. They renamed the Sundays as ‘of Easter’ rather than ‘after Easter’, and chucked out the old collects for the Sundays after Easter ... because they didn’t consider them ‘Paschal’ enough.” (The “old” collects to which he refers are all found in the Gelasian Sacramentary in the same places they have in the Missal of St Pius V.) Likewise, St Fulbert’s original conclusion makes no direct reference to Easter. For further reference, see these articles about the supposed restoration of the 50 days of Easter:

http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2019/05/fifty-days-of-easter.html http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2019/06/fifty-days-of-easter-part-2.html

Thursday, April 24, 2025

Medieval Vespers of Easter

Gregory DiPippoAt the beginning, the customary “Deus in adjutorium” is replaced by the Kyrie of the Mass Lux et origo, which is given as Mass I in the modern Liber Usualis. The first three psalms of Sunday Vespers, 109, 110 and 111, are sung with a single antiphon consisting of four Alleluias, followed by the gradual and alleluia of the Mass. The second part of the gradual varies from day to day, just as it does at the Mass; the alleluia is often different from that of the day’s Mass, or made longer by the addition of a second verse. In many Uses, but not that of Sarum, the sequence Victimae Paschali was said as well. There follow the Magnificat with its antiphon, and a prayer, in the customary manner.

At this point, the procession to the baptismal font is formed in the following order: the cross-bearer, two acolytes carrying candles, the thurifer, two deacons who carry the holy oil and the chrism, a server to carry the book, and the celebrant, followed by the leaders of the choir (called “rectors” at Sarum), and the rest of the clergy. A rubric of the Sarum Breviary notes that it was not their custom to carry the Paschal candle at the head of this procession, indicating that this was certainly done elsewhere.

Before the procession starts, the rectors intone an antiphon, “Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia,” which is completed by the choir. They then begin the fourth psalm of Sunday Vespers, 112; one “Alleluia” is sung after each verse, and the procession begins moving after the first verse is completed. It makes it way to the baptismal font, where the first verse of the psalm and then the antiphon are repeated, and the font is incensed, after which the celebrant sings a versicle, the choir sings the response, and the celebrant sings a prayer. Many Uses added the Vidi aquam to this part of the ceremony.

|

The Baptistery of St John in the Lateran in Rome, photographed by William Henry Goodyear (1846-1923); from the Brooklyn Museum archives via Wikimedia Commons. (The current baptismal font of Salisbury Cathedral is comically hideous.)

|

The procession then returned to the main choir, while singing a Marian antiphon, also followed by another versicle and prayer; at Sarum, this antiphon varied each day of the octave, while in other Uses, such as that of the Dominicans, the Regina caeli was sung every day. At the end, Benedicamus Domino and Deo gratias are sung with two Alleluias as in the Roman Rite.

It should be obvious that this ritual had its origins in the very ancient days of the Church, when the newly baptized would return each day of the Easter octave to the font where they had been reborn in Christ on the eve of Holy Saturday. The eminently baptismal character of the ceremony also explains why it is not in the Roman Breviary, a form of the Office originally used in the chapel of the Papal court, which was not a parish, and hence had neither catechumens nor a font. In fact, the Ordinal of Pope Innocent III, which lays out this form of the Office in the early 13th century, contains a rubric noting that Vespers of Easter was done in a completely different manner in the Lateran Basilica from that done in the Papal chapel. This is also why we find that in the Dominican Use, the entire portion which was sung while processing to the font (Psalms 112 and 113) is simply dropped, since the earliest Dominican churches would not have been parishes, and hence not had baptismal fonts.

The most common variant of this rite, as noted above, was the singing of a responsory while processing to chapel of the Cross, instead of Psalm 113 as at Sarum. This beautiful text is attributed to King Robert II of France (972-1031), also known as Robert the Pious.

R. Christus resurgens a mortuis jam non moritur, mors illi ultra non dominabitur: * Quod enim vivit, vivit Deo, alleluia, alleluia. V. Dicant nunc Judaei, quomodo milites custodientes sepulchrum perdiderunt Regem ad lapidis positionem: quare non servabant petram justitiae? Aut sepultum reddant, aut resurgentem adorent nobiscum, dicentes: Quod enim vivit.

R. Christ rising again from the dead, dieth now no longer, death shall no longer have dominion over Him: * For in that He liveth, He liveth unto God, alleluia, alleluia. V. Let the Jews now say how the soldiers that guarded the tomb lost the King where the stone was laid: why did they not keep the stone of justice? Let them either give back Him that was buried, or with us adore Him as he riseth, saying: For in that He liveth…

To catalog of all the variants of this ceremony found in medieval liturgical Uses would be a truly Herculean task, since there do not seem to be two cathedrals in all of Europe that did it in quite the same way. One more text, this remarkable antiphon from the Use of Paris, calls for particular notice; the very simple rubrics of the Parisian Breviary of 1492 simply say that it was sung “ad crucem”, i.e., the cross on top of the rood screen.

Aña Ego sum Alpha et Ω, (omega) primus et novissimus, initium et finis, qui ante mundi principium et in saeculum saeculi vivo in aeternum. Manus meae, quae vos fecerunt, clavis confixae sunt; propter vos flagellis caesus sum, spinis coronatus sum; aquam petii pendens, et acetum porrexerunt; in escam meam fel dederunt et in latus lanceam; mortuus et sepultus, resurrexi, vobiscum sum. Videte, quia ego ipse sum et non est Deus praeter me, alleluia.

Aña I am the Alpha and Omega, the first and last, the beginning and the end, who before the beginning of the world, and unto all ages live forever. My hands, which made ye, were fixed with nails; for ye I was scourged, I was crowned with thorns; as I hung, I asked for water, and they offered vinegar. They gave Me gal for food, and a spear in My side. Being dead and buried, I rose, I am with ye. See that it is I, and there is no God beside me, alleluia.

|

| The reliquary of the Crown of Thorns, by Viollet-Le-Duc in 1862 and preserved at Notre-Dame de Paris. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by PHGCOM.) |

Thursday, April 03, 2025

Music for Lent: The Media Vita

Gregory DiPippoR. In the midst of life, we are in death; whom shall we seek to help us, but Thee, o Lord, who for our sins art justly wroth? * Holy God, holy mighty one, holy and merciful Savior, hand us not over to bitter death. V. Cast us not away in the time of our old age, when our strength shall fail, forsake us not, o Lord. Holy God, holy mighty one etc.The Use of Sarum appointed Media vita to be sung at the same time as the Dominicans, during the third and fourth weeks of Lent, but with more verses, and the division of the refrain as follows:

Aña In the midst of life, we are in death; whom shall we seek to help us, but Thee, o Lord, who for our sins art justly wroth? * Holy God, holy mighty one, holy and merciful Savior, hand us not over to bitter death.Many composers have put their hand to this text; one of the finest versions of it is the setting by the Franco-flemish composer Nicolas Gombert. (1495-1560 ca.)

V. Cast us not way in the time of our old age, when our strength shall fail, forsake us not, o Lord. Holy God.

V. Close not Thy ears to our prayers. Holy mighty one.

V. Who knowest the secrets of the heart, show mercy to our sins. Holy and merciful Savior, hand us not over to bitter death.

Saturday, January 25, 2025

Historical Falsehoods about Active Participation: A Response to Dr Brant Pitre (Part 4)

Gregory DiPippoThis is the fourth part of my response to a video by Dr Brant Pitre of the Augustine Institute about popular participation in the liturgy. (part 1; part 2) At the conclusion of the third part, I stated that in any defense of the post-Conciliar reform, it is necessary to mispresent the history of the liturgy in the Tridentine period, and Dr Pitre begins to do this at the 31:00 mark. In matters of history, precision matters, and this part of the presentation is very lacking in precision.

His essential contention is that because the liturgical books of the Tridentine period contain no clear directives for lay participation (31:12), there was no lay participation. As I have explained in the previous articles of this series, the liturgical books never had any directives for lay participation, either before or after the Tridentine reform. This lack “in the five-hundred years after the Council of Trent” is unfavorably contrasted with the active lay participation that supposedly predominated “in the first thousand years of the Latin Rite.” (Five hundred years have not passed since the beginning of the Council of Trent in 1545; indeed, the four-hundredth anniversary of its closing, Dec. 4, 1963, was the day the first documents of Vatican II were formally promulgated, including, most ironically, Sacrosanctum Concilium.) |

| The cathedral of St Donatianus in Bruges (now part of the modern state of Belgium) in 1641; destroyed in 1799 by the occupying French Revolutionary Army. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.) |

|

| Dom Guéranger |

|

| The beginning of the Canon in a hand missal for the laity, translated into German; this book was published within a decade of the end of the Council of Trent. |

|

| Another in English, from roughly 1660. |

|

| A French example from the first decade of the 17th century. |

Saturday, January 18, 2025

Historical Falsehoods about Active Participation: A Response to Dr Brant Pitre (Part 3)

Gregory DiPippoThis is the third part of my response to a video by Dr Brant Pitre of the Augustine Institute on the subject of popular participation in the Mass. In the previous part, I explained the errors of his claims about the nature of the Roman stational Masses, and of an ancient document which describes them, and then, the erroneous contrast which he draws between them and the Masses celebrated in the papal chapel. By repeatedly calling the latter “private Masses”, without further qualification, he gives the false impression that these were exclusively low Masses, which had no place for the participation of the lay faithful. In this telling, such low Masses were then adopted by the Franciscans when they took on the specific form of the Roman liturgy used in the papal chapel.

At 26:10, Dr Pitre says about this liturgical form that it doesn’t have “any clear directive for how the people are supposed to be engaged, because the people by and large were not present at private Masses in the papal chapel.” Therefore, when the Franciscans spread this specific form of the liturgy throughout Europe, they effectively injected into the Church’s bloodstream a habit of lay non-participation in the Mass. (This is my metaphor, not his.) |

| The choir of the cathedral of St Lawrence in Genoa. Not designed for low Mass. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Benjamin Smith, CC BY-SA 4.0.) |

|

| The upper basilica of St Francis in Assisi. Also not designed for low Mass. |

|

| A page of the rite of Mass in the rubrics of the Missal of St Pius V; the section in italics at the lower right describes the beginning of the solemn Mass. |

|

| The nave of the church of the Holy Name of Jesus in Rome, commonly known as ‘il Gesù’, the principle Jesuit church in the city. Note the position of the preaching pulpit, which is nowhere near the sanctuary. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Finoskov, CC BY-SA 4.0.) |