Sketch by Peter F. Anson

A review of Carl Van Treeck and Aloysius Croft, Symbols in the Church (Romanitas Press, 2021) and Peter F. Anson, Churches: Their Plan and Furnishing (Romanitas Press, 2021)

It is a fact without doubt that the Roman Missal represents in its entirety the loftiest and most important work in ecclesiastical literature, being that it shows forth with the greatest fidelity the life-history of the Church, that sacred poem in the making of which ha posto mano e cielo e terra [“Heaven and earth have set their hand,” Dante, Paradiso XXV,2].[1]

The temple of Solomon… was not alone the binding of the holy book; it was the holy book itself. On each one of its concentric walls, the priests could read the word translated and manifested to the eye, and thus they followed its transformations from sanctuary to sanctuary, until they seized it in its last tabernacle… Thus the word was enclosed in an edifice.[2]

Here is a riddle: What are the three most important books in Catholic life that are not books? The answer is: the Bible (which, despite its modern binding, is not a book but a library of works co-authored by the Holy Spirit ); the traditional Roman Missal (which, though also appearing in book form, is a set of instructions for a sacred action); and the church (a building that, like the Holy Temple, is meant to be read cover to cover).

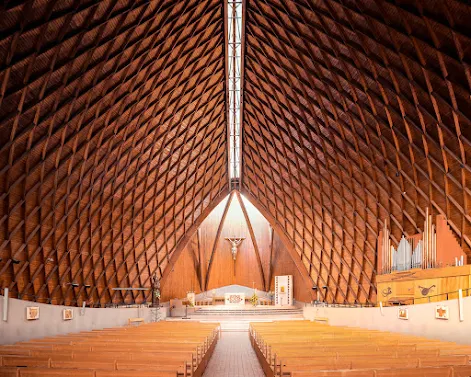

But if it is true that the church, like all great architecture, is a book (Victor Hugo calls architecture the great book of humanity), then it takes training to read it. One must learn its alphabet and grammar, so to speak, in order to understand its sentences and paragraphs. And yet not many people today are artistically or architecturally literate. One of modern Catholicism’s deficiencies is the widespread inability of its faithful to decipher the symbols of their Faith.

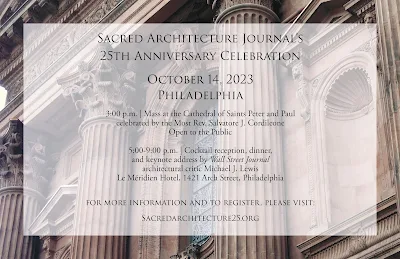

It is for this reason that we can be grateful to Romanitas Press for republishing two volumes on the subject: Carl Van Treeck and Aloysius Croft’s 1936 Symbols in the Church and Peter F. Anson’s 1947 Churches: Their Plan and Furnishing.

Peter Anson (1889-1975) was a restless and talented soul. Born near the sea in Portsmouth, England and trained as an architect, he entered an Anglican Benedictine monastery in 1910. Three years later, he and his community submitted to the Holy See and became Catholic. Anson eventually became an Oblate and the monastery’s librarian; he also founded the Apostleship of the Sea for Catholic seafarers. After a breakdown in health, however, Anson decided to return to the world, and at the age of 35 he earned a living as an artist while seeing the world. He became a Franciscan Tertiary for a while in Italy but returned to his nomadic life before eventually settling down in a village of sailors and fisherman in Macduff, Scotland, where he could savor the life of the sea once more.

Anson wrote Church Plans as a practical guide for building and remodeling churches. The author wisely cautions against altering churches simply because they do not conform to contemporary sensibilities, and he frowns upon antiquarian and unimaginative resuscitations of earlier styles. His language of functionalism and his disdain for “fancy symbolism” are slightly troublesome, for they could be interpreted as an excuse to produce barren barns and call them churches. But Anson himself does not go in this direction: his meticulous illustrations and moderate counsel open the reader up to the riches of sacred architecture. Anson faithfully operates within the strictures of the 1917 Code of Canon Law and other Church legislation. His summary of these regulations is quite useful, although not all of it is still valid, such as the prohibition of electric lights for illuminating the altar (112).

As you may have guessed from his biography, Anson was an eccentric fellow, and Church Plans is an eccentric work. The author does not shy from offering his own advice in addition to official Church rules. Pulpits, he opines, should be elevated, made of wood (“it looks warmer and gives more color to a church”), and have a door (“many an eloquent preacher would feel far more at his ease if knew there was no danger of falling backwards”) and a solid front (“it is distracting to see the preacher’s cassock and feet”)(156). He also holds the odd view that if the weather were perfectly clement every day, we would not need churches at all but would celebrate Mass in an open field (3). He seems to forget that churches do not simply provide shelter from the rain but, among other things, help keep our minds from wandering.

The chief weakness of Church Plans is that it tries to square the circle between traditional architecture and modernist. Anson quotes passages that advocate placing the altar in the center of the church and advises a “happy mean” between the new view and the old (39). But how can you have a happy mean between an altar in the center of the church and an altar at the end: placing it three-quarters of the way in? Fortunately, Anson’s go-to authority on practical matters is St. Charles Borromeo, so he almost never ends up recommending something silly. And although he includes illustrations of modernist abominations (there is a bleak, free-standing altar for Mass facing the people from 1935 Germany), his own rich sketches betray the stark differences. After being enchanted by page after page of beautiful churches, seeing a design by Hans Herkommer or Eric Gill is like a punch in the gut.

Sketch by P.F.

Anson. Yes!

Sketch by P.F. Anson. No!

Although Church Plans is thin on symbolic explanations, it is nonetheless useful for gaining a better understanding of the meaning and parts of a church. Equipped with this understanding, readers can then continue their education in sacred architecture with the works of men like Duncan Stroik.

Carl Van Treeck and Aloysius Croft’s Symbols in the Church was also written as a practical guide for artists and “ecclesiastical craftsmen” rather than students of symbolism (vi). Annotations are scarce as well as scholarly explanations of styles, historical context, etc. Like Church Plans, the images are illustrated with black-and-white sketches rather than photographs. The disadvantage of this choice is that the image is more dependent on the viewpoint of the artist; the advantage, however, is a unity of presentation, a greater beauty, and, in this case, the superior viewpoint of the artist, Carl Van Treeck.

The basic idea behind Symbols in the Church is to introduce artists to “the beautiful picture language” of the Mystical Body of Christ (vi) so that they can adapt these symbols to contemporary use. Happily, the authors did not follow their own rule strictly but included some early representations of Christ that are no longer recognizable as such, e.g., a griffin, a peacock, a phoenix, and a bird in a cage (representing gestation in His mother’s womb!). As a result, the reader catches something of the breadth and depth of Catholic symbolism, which has varied from century to century and place to place.

Symbols in the Church begins with an interesting chapter on symbols and symbolism in which the authors argue that all Christian art must necessarily be symbolic because Christian art portrays some element of the supernatural. (“Sheer naturalness” they state earlier, is “the death of all liturgical art” [vi]). The rest of the book is divided according to subject matter: the Holy Trinity, God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Ghost, the Gospels and Evangelists, the Apostles, the Church, the Sacraments, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Ecclesiastical Year, and the Four Last Things.

The entire book is a delight to peruse, but I was especially fascinated by the symbols of the Church, some of which surprised me (there are a lot more than just Noah’s Ark and Peter’s Barque). And I was struck by an image of the Last Judgment depicting scales, one of which is filled with the cross, the anchor, and the crown of thorns, the other of which is laden with jewels. The latter tilts upward: the virtues and sufferings of the faithful soul outweigh the riches and comforts of the world.

Plate XXXVIII of Symbols in the Church. Symbols of death (1 and 2), judgment (3 and 4), and damnation (5).

Church Plans and Symbols in the Church fit hand in glove: Anson more or less tells you how to build a church, and Van Treeck and Croft tell you how to decorate it. I recommend these books to anyone interested in Catholic art and architecture but especially as gifts to priests and planning committees in charge of building or remodeling churches. God willing, with aids like these, “writing” beautiful churches will once again become common.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)