A friend of mine sent me a fascinating essay, “Liturgical Silence” by Charles Harris, from an Anglican collection of studies called

Liturgy and Worship (1932), ed. W. K. Lowther Clarke. I was so taken with it that I decided to present a summary with generous quotations and some applications to our present liturgical life.

Harris brings forward an abundance of quotations from the earliest liturgical sources to support his contention that the silent recitation of part or all of the Anaphora or Canon of the Eucharistic liturgy became the norm very early on in both East and West. This evidence—and more importantly, the underlying theology and spirituality to which it points—is a clarion call for Catholics of the Roman Rite to continue to work zealously for either the preservation and spread (in the

usus antiquior) or the reappraisal and restoration (in the Novus Ordo) of the silent Canon. This ancient and longstanding custom, like the

ad orientem stance and the exercise of liturgical roles by ordained ministers, expresses the great reverence due to our Lord Jesus Christ in the most Blessed Sacrament.

Harris first talks about the psychology of silence, saying:

[T]he effect of silence (or of subdued or whispered speech) is to lull the outward senses into a receptive condition; to induce tranquillity, repose, and inward peace; to relax the tension of the nervous system; and gradually to induce a state of restful waiting upon God, which opens the ‘subconscious’ or ‘unconscious’ mind to the influence of grace and religious suggestion. (775)

Those who attend quiet Low Masses are aware of the profound peace and sacred stillness that can reign in the soul as in the church building itself, and as much as I am an ardent advocate of the sung High Mass, I recognize, too, that there is a precious devotional value, a mystical-ascetical power, in the

Missa lecta or

Missa recitata. But it has also frequently struck me, as a choirmaster, how much silence there can be even in the midst of a sung Mass, whether it be during the Canon or around the time of the communion of the priest. The old Roman Rite in general has the character of an entering into God’s “rest,” that mysterious Sabbath rest of the seventh day that anticipates the glory of the everlasting eighth day of heavenly bliss.

In second place, Harris attempts to locate the origin of the transition from a spoken Anaphora to a partially or completely silent one.

At an early but undetermined date, it gradually became customary, both in the East and in the West, to recite certain of the most solemn Eucharistic prayers, particularly the greater part of the Canon, in a very low or inaudible voice. Such recitation was termed ‘mystic’ (mystikos), an epithet which sufficiently indicated its significance. … It evinced just such an overpowering sense, not merely of humility, but even of ‘abjection’ and ‘nothingness,’ as befits a creature admitted to the immediate presence of its Creator. (775)

Almost as an aside, Harris dares a general judgment about the character or feel of Catholic worship as compared with Protestant:

There are obvious disadvantages, both of a devotional and of an intellectual kind, in the silent recitation of the Canon or Anaphora. On the other hand, it can hardly be denied that the ‘mystic’ prayer of the celebrant has been a prime factor in creating that thrilling atmosphere of rapt adoration which has been the distinctive feature of Catholic worship throughout the ages; and which the more intellectual, instructive, and ‘edifying’ worship of modern Protestants seems unable to evoke. (776)

Reading these words caused me to cringe when I realized that his description of “Catholic” matched the

usus antiquior while his description of “Protestant” lined up with the Novus Ordo—intellectual, instructive, and (in the best cases) edifying, as its architects intended it to be, but not typically characterized by a “thrilling atmosphere of rapt adoration.” I would maintain, in fact, that many Catholics who have fled from the Ordinary to the Extraordinary Form have done so not exclusively or primarily to escape the rampant abuses, but more so to find a spiritual refuge that encourages meditation and adoration. It is a quasi-monastic “flight from the world” in order to find God. If we do not encounter the living God in prayer and go out of ourselves to worship Him in spirit and in truth, we will be hopeless when it comes to living a Christian life in the workaday world. A certain alternating rhythm of interior recollection and outward engagement is necessary, and perhaps it is the relentless emphasis, in the Novus Ordo context, on the outward, the busy, the active, the evangelistic, that has drained Catholics of their deepest spiritual resources for battling the world, the flesh, and the devil.

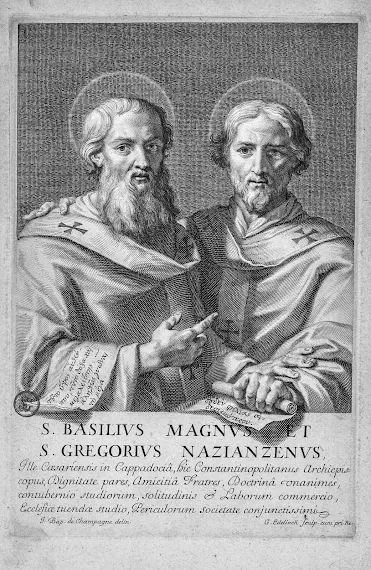

Third, Harris argues that the silent or ‘mystic’ recitation of the Anaphora is bound up with an ever more heightened emphasis, in liturgical texts as in preaching, on the awesome reality of the divine mysteries of Christ’s Body and Blood entrusted to the Church. Although “even from the beginning of Christianity some degree of awe and dread accompanied the celebration of the Holy Mysteries, as is clear from the language of St. Paul (1 Cor. xi.26-33)” (776), we can trace this awareness most clearly in the three main Eastern liturgies, those of St. James, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Basil.

Harris argues that the Liturgy of St. James, bearing within itself the early liturgy of Jerusalem, already substantially existed in its present form as early as 348, and places its composition at 330-335 because of its allusions to Nicene Christology. What is more relevant to our purpose here than the date is the description Harris offers:

An atmosphere of mystical awe pervades the whole of this Liturgy. The worshippers are said to be ‘full of fear and dread’ while they offer ‘this fearful and unbloody sacrifice,’ which is further described as a ‘fearful and awe-inspiring (phriktēs) ministration.’ After consecration, the elements are spoken of as ‘hallowed, precious, celestial, ineffable, stainless, glorious, terrible (phoberon), dreadful (phrikton), divine (theon).’ (777)

Many similar phrases from St. Cyril of Jerusalem are brought in to confirm the point that this is familiar language for the Christians of this period, the middle of the fourth century.

The Liturgy of St. Basil, attributed with good reason to the saint (ca. 330-379) himself, is no different:

A sense of ‘numinous’ awe pervades this Liturgy, which speaks of the Mysteries as not only ‘divine, holy, spotless, immortal, heavenly, and quickening’; but also as ‘tremendous’ or ‘fearful’ (phrikton, literally ‘to be shuddered at’). (778)

Harris believes that Chrysostom’s remarks on 1 Corinthians 14:16 suggest that

parts of the Anaphora were recited audibly, especially the concluding words “for ever and ever,” giving the cue for the people’s response of “Amen”—exactly as the Roman Rite has the priest say or sing

per omnia saecula saeculorum, with the same response.

In terms of witnesses of universal practice in the early Church, we have a stunning homily from a Nestorian source, Narsai, of the late fifth century (Narsai died in 502), who tells us in Homily 17 that after the

Sursum corda and before the

Sanctus,

all the ecclesiastical body now observes silence, and all set themselves to pray earnestly in their hearts. The Priests are still, and the deacons stand in silence . . . the whole people is quiet and still, subdued and calm . . . The Mysteries are set in order, the censers are smoking, the lamps are shining, and the deacons are hovering and brandishing [fans] in likeness of watchers [i.e., angels]. Deep silence and peaceful calm settles on that place: it is filled and overflows with brightness and splendour, beauty and power. (779)

Narsai goes on to note that the Priest pronounces the Epiclesis inaudibly, because he is worshipping “with quaking, and fear, and harrowing dread,” and yet that the moment of the Epiclesis is proclaimed by a herald to the congregation, so that they may be duly moved to reverence and adoration. The herald cries: “In silence and fear be ye standing: peace be with us. Let all the people be in fear at this moment in which the adorable Mysteries are being accomplished by the descent of the Spirit.”

Harris concludes this treatment of oriental liturgies by noting that the practice of the silent or ‘mystic’ recitation of the Anaphora was the established and official use of all rites by the close of the eighth century—and this, in spite of the fact that the Emperor Justinian attempted, in 565, to prohibit the practice by imperial decree, requiring that the priest say all the prayers of the liturgy aloud! At least at the time Harris was writing, evidence indicated that the same practice of silent recitation obtained in the Roman Rite from at least the eighth century.

Lastly, Harris, having summarized the Anglican tradition’s emphasis on the spoken vernacular word, makes a practical proposal for the Anglican Church, of which he is a member, with a view to recovering something of the mystical dimension that had been lost. His advice, however, ends up having a strange relevance for Roman Catholics today, as we seek ways to celebrate the modern Roman Rite by reference to the “gold standard,” the traditional Roman Rite, its ancestor and exemplar:

An audible voice need not be a loud voice. It is possible to obtain the full ‘mystical’ effect of silence by reciting the Canon in a very low and subdued voice, fully audible to every careful listener in the church, and yet expressive and suggestive of the deepest religious awe. It is not desirable, for the sake of one or two partially deaf persons, to raise the voice, and thus impede the devotion of the general congregation, which is fostered and augmented by the use of a subdued tone of voice. (782)

While I do not concur with Harris that one can obtain the

full mystical effect of silence with a Canon that is recited aloud but more quietly, the trend of his advice is surely sane and sound. It reminds me of Cardinal Ratzinger’s suggestion that we would do well to reexamine whether parts of the Canon should once again be prayed silently, to invite the appropriate response of prayerful reverence, which, ironically, the constant recitation of familiar texts has a way of diminishing, if not excluding altogether.

There is a more general lesson in Harris’s research: when it comes to the silent or ‘mystic’ recitation of the Canon, we are looking at a custom that go back to the middle of the first millennium of Christianity. For those who value what is ancient, this is ancient indeed; and since man’s needs are fundamentally the same from age to age, the Church, having found early on the liturgical approach that fit best with the reality being celebrated and the persons being saved, preserved that approach jealously for all the centuries thereafter. “The Lord is in his holy temple: let all the earth keep silence before him” (Hab 2:20).

For those who think modern man needs something different from the man of every other age, the ancientness of a custom carries no weight. But in order to be fully consistent, the modernist must never shore up his positions by appealing to ancient practices or testimonies; he must fashion his liturgy whole cloth from out of his own head, without reference to the past. Once the criterion of tradition as such is laid aside as inappropriate for modern man, any choice from a past century or millennium will be merely arbitrary or political.

Everyone who maintains that we ought to worship in continuity with our forefathers can gratefully receive the liturgy from their hands—with its fundamental characteristics that have never changed at all, like the eastward orientation of clergy and people, as well as with those characteristics that received their definitive shape in the Patristic period and were not abandoned until the arrogant experimentation of the 1960s.